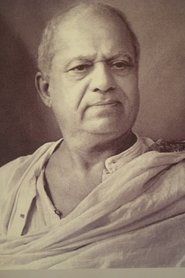

Raja Harishchandra

Plot

The film follows the legendary King Harishchandra, known for his unwavering commitment to truth and righteousness. After being tested by the sage Vishwamitra, the king promises to give his entire kingdom to the sage, which he honors despite the devastating consequences. Forced to live in poverty with his wife Taramati and son Rohitashva, Harishchandra faces further trials when his son dies from a snake bite. The ultimate test comes when Taramati is accused of murder and the king, now working as a crematorium guard, must sentence his own wife to death. The gods, impressed by his devotion to truth, intervene at the last moment, restoring his kingdom and resurrecting his son.

About the Production

Dadasaheb Phalke traveled to London in 1910 to learn filmmaking techniques and purchased equipment from Williamson Camera. He built his own camera and processing facilities in India. The film was shot over 7 months with a small crew and minimal resources. Many scenes were filmed outdoors due to lack of studio space. Special effects were created using in-camera techniques and manual manipulation.

Historical Background

The film was made during the British colonial period in India, a time of growing Indian nationalism and cultural renaissance. The early 1910s saw a resurgence of interest in Indian mythology and traditional arts as a form of cultural resistance to British influence. Cinema itself was a new medium, having been invented only two decades earlier. The film industry was dominated by Western productions, and there was no indigenous film industry in India. Phalke's decision to make a film based on Indian mythology was both a cultural statement and a strategic business decision, as stories from the epics were familiar to Indian audiences. The film's creation coincided with the Swadeshi movement, which promoted indigenous industries and cultural revival.

Why This Film Matters

Raja Harishchandra single-handedly launched the Indian film industry, which today produces more films annually than any other country. It established mythological films as a popular genre that would dominate early Indian cinema. The film demonstrated that Indian stories could be successfully adapted to the new medium of cinema, paving the way for thousands of filmmakers. It created a new art form that would become integral to Indian cultural identity. The film's success proved that cinema could be commercially viable in India, leading to the establishment of Bombay as the center of Indian film production. The Dadasaheb Phalke Award, instituted in 1969, remains India's highest award in cinema, named after the film's director.

Making Of

The making of Raja Harishchandra was fraught with challenges. Dadasaheb Phalke, initially a photographer and printing press owner, was inspired to make films after watching 'The Life of Christ' in 1910. He traveled to London to study filmmaking but returned to India to create something rooted in Indian culture. The production faced numerous obstacles including lack of trained actors, technical equipment, and studio facilities. Phalke had to train his actors from scratch, many of whom had never seen a film before. The film was shot in natural light using a hand-cranked camera. Special effects were achieved through primitive techniques including matte paintings and stop-motion. The processing of the film was done in makeshift darkrooms, often in the bathroom of Phalke's residence. Despite these challenges, Phalke's determination and innovative approach resulted in a technically impressive film for its time.

Visual Style

The cinematography was primitive for its time but innovative within the Indian context. Shot on a hand-cranked camera using natural light, the film employed basic techniques like long takes and static camera positions typical of early cinema. However, Phalke demonstrated creativity in composition and staging, using theatrical blocking adapted for the camera. The film included special effects techniques such as dissolves, superimpositions, and stop-motion animation, which were advanced for the time. The visual style was influenced by traditional Indian art forms, including painting and temple sculpture, with careful attention to costume and set design reflecting Indian aesthetics.

Innovations

Raja Harishchandra pioneered several technical achievements in Indian cinema. Phalke built his own camera and developed film processing techniques in India, which were previously unavailable. The film featured special effects including the appearance of gods and supernatural elements using double exposure and other in-camera tricks. Phalke developed techniques for creating elaborate costumes and sets with limited resources. The film demonstrated sophisticated editing techniques for its time, including cross-cutting between parallel action sequences. Phalke also experimented with color tinting in some prints, hand-coloring certain scenes to enhance their dramatic impact.

Music

As a silent film, Raja Harishchandra had no recorded soundtrack. However, during screenings, live music was typically provided by musicians using traditional Indian instruments. The musical accompaniment often included harmonium, tabla, and sitar, playing classical Indian ragas appropriate to the mood of different scenes. Some theaters employed narrators who would explain the story and read out intertitles for illiterate audiences. The absence of recorded sound made visual storytelling particularly important, which Phalke accomplished through expressive acting and clear visual narrative.

Famous Quotes

'I must keep my word even if it costs me my kingdom' (King Harishchandra)

'Truth is the highest dharma' (repeated theme throughout the film)

Memorable Scenes

- The coronation scene where King Harishchandra takes his oath of truth

- The transformation scene where Vishwamitra tests the king's resolve

- The emotional scene where the king sells his wife into servitude

- The climax at the cremation ground where divine intervention occurs

Did You Know?

- This is considered India's first full-length feature film and the beginning of Indian cinema

- Director Dadasaheb Phalke is often called the 'Father of Indian Cinema'

- Female roles were played by male actors as no women were willing to act in films at that time

- Phalke mortgaged his wife Saraswati's jewelry and sold his printing press to finance the film

- The film was inspired by Phalke watching a silent film about the life of Christ

- Only about 1,500 feet of the original 3,700 feet of film survives today

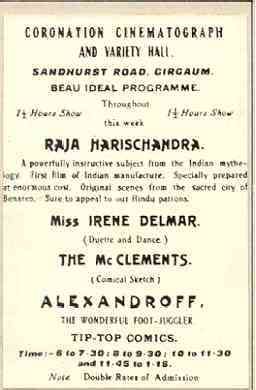

- The premiere was held at Coronation Cinema in Girgaon, Mumbai

- Phalke made his wife develop the film in the bathroom of their house

- The film's success led to the establishment of India's first film industry in Bombay

- A special screening was arranged for the British Viceroy Lord Hardinge

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film's technical achievements and its successful adaptation of Indian mythology to cinema. The Times of India gave it a positive review, noting its impressive special effects and faithful storytelling. Modern critics and film historians regard it as a pioneering achievement that established many conventions of Indian cinema. It is celebrated for its technical innovation despite limited resources and its cultural significance in establishing an indigenous film industry. The film is studied in film schools worldwide as an example of early cinema's global reach and cultural adaptation.

What Audiences Thought

The film was an immediate commercial success, drawing large crowds in Bombay and other cities where it was screened. Audiences were fascinated by seeing Indian stories and characters on screen for the first time. The film ran for extended periods in theaters, an unusual achievement for that era. Many viewers reportedly performed puja (worship) before the film screenings, treating the cinema hall as a temple. The success of Raja Harishchandra encouraged other entrepreneurs to invest in film production, leading to the rapid growth of the Indian film industry in the following years.

Awards & Recognition

- Dadasaheb Phalke Award (posthumously named after the director)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The Life of Christ (1903)

- Georges Méliès' fantasy films

- Traditional Indian theater forms

- Hindu mythology and epics

- Classical Indian painting

This Film Influenced

- Lanka Dahan (1917)

- Kaliya Mardan (1919)

- Satyavan Savitri (1923)

- Shirin Farhad (1931)

- Jai Santoshi Maa (1975)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is partially preserved with only fragments surviving. Approximately 1,500 feet of the original 3,700 feet of film exists today. The National Film Archive of India (NFAI) in Pune holds the surviving fragments. Some portions have been restored and digitized for preservation. The incomplete nature of the surviving print makes it difficult to view the film as originally intended, but efforts continue to preserve what remains of this landmark film.