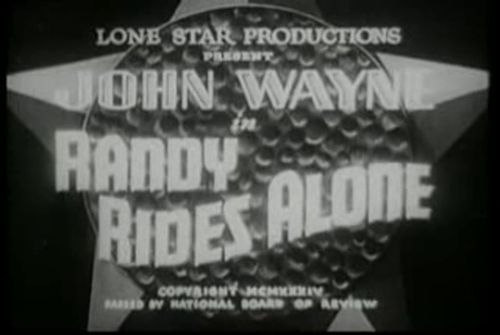

Randy Rides Alone

"A FUGITIVE FROM JUSTICE... HUNTED BY THE LAW AND THE KILLERS!"

Plot

Randy Bowers arrives in the town of Alamosa and walks into the local saloon just as a gang of ruthless bandits, led by the mysterious Matt the Mute, burst in and murder several patrons including the saloon owner. Unaware that Matt is secretly collaborating with the town's corrupt sheriff who believes Matt is merely a deaf-mute informant, Randy is framed for the killings and arrested. With the help of Sally Rogers, the niece of the murdered saloon owner, Randy escapes from jail and becomes a fugitive, hunted by both the law and the real killers. His flight leads him directly to the bandits' mountain hideout where he discovers the truth about the conspiracy and must fight to clear his name and bring the real murderers to justice.

About the Production

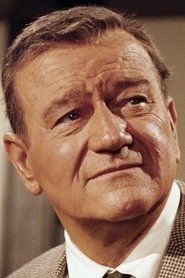

Filmed in just 6 days on a tight schedule typical of poverty row westerns. The cave sequences were shot on studio sets with painted backdrops. This was one of 8 westerns John Wayne made for Lone Star in 1934 alone, demonstrating the factory-like production methods of B-movie westerns.

Historical Background

Released during the Great Depression in 1934, 'Randy Rides Alone' was part of the flood of low-budget westerns that provided affordable entertainment to struggling Americans. The film emerged during the Hays Code enforcement era, though its violence pushed boundaries. 1934 was also the year of the Production Code's strict implementation, making the film's opening massacre scene particularly notable. The western genre was experiencing a transition from silent to sound, with films like this helping establish the conventions of the talking western. This was also during the period when John Wayne was typecast in B-westerns, before John Ford would elevate him to A-list status.

Why This Film Matters

While not a landmark film, 'Randy Rides Alone' represents the typical B-western that dominated American cinema in the 1930s and shaped public perceptions of the Old West. It's part of John Wayne's formative period, where he honed the screen persona that would later make him an American icon. The film's public domain status has made it accessible to generations of viewers, contributing to the enduring popularity of classic westerns. It also exemplifies the poverty row production system that allowed hundreds of films to be made quickly and cheaply, preserving working-class entertainment history.

Making Of

The production was rushed through in less than a week, with director Harry L. Fraser working from a minimal script that allowed for improvisation. John Wayne, still years away from stardom, was developing his screen persona through these rapid-fire productions. The cave sequences were particularly challenging, shot on cramped studio sets with limited lighting. Alberta Vaughn, a popular silent film actress transitioning to talkies, was nearing the end of her career when she made this film. George 'Gabby' Hayes was still establishing the character that would make him famous, and this film shows him in a more serious role than his later comic performances.

Visual Style

Shot by Archie Stout, who would later work with John Wayne on major productions like 'The Quiet Man.' The cinematography is functional rather than artistic, utilizing natural light for outdoor scenes and standard studio lighting for interiors. The Alabama Hills locations provide striking backdrops that would become synonymous with westerns. The camera work is straightforward, focusing on clear storytelling rather than visual innovation.

Innovations

No significant technical innovations, but represents the efficient production methods of poverty row studios. The film demonstrates how westerns could be produced quickly using limited resources while maintaining genre conventions. The cave sequences show creative use of studio space to create convincing location settings.

Music

Typical of low-budget productions, the film uses library music and minimal original scoring. The sound quality reflects the early talkie era, with some synchronization issues noticeable in dialogue scenes. No notable songs or musical themes were created specifically for this film. Sound effects were basic, using standard western audio clichés of the period.

Famous Quotes

I'm not running from the law, I'm running from a rope!

A man's got to clear his name, even if it means riding straight into hell.

In this town, justice wears a badge and the outlaws wear smiles.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening saloon massacre where Matt the Mute and his gang burst in guns blazing, establishing the film's violent tone and setting the frame-up plot in motion. The scene was particularly shocking for 1934 audiences and sets up the entire conflict.

Did You Know?

- This was one of over 20 low-budget westerns John Wayne made between 1933-1935 before his breakthrough with 'Stagecoach' in 1939

- George 'Gabby' Hayes developed his famous gabby sidekick character through films like this, though he doesn't play his usual comic relief role here

- The film's villain 'Matt the Mute' was an unusual character for westerns of the era, as most villains were more overtly menacing

- Lone Star Productions was created specifically to produce John Wayne westerns, making 16 films with him between 1933-1935

- The film was shot in sequence, a common practice for low-budget productions to save time and money

- Despite the title, Randy spends most of the film on foot rather than riding

- The bar massacre scene was considered particularly violent for 1934 standards

- This film exists in the public domain, which is why it's widely available on budget DVD collections

- The Alabama Hills location where this was filmed would later become famous as the setting for countless westerns and television shows

- John Wayne's salary for this film was approximately $2,500, a significant increase from his earlier poverty row work

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews were minimal, as B-westerns received little critical attention. The few trade publications that reviewed it noted it as 'adequate entertainment' and 'standard western fare.' Modern critics view it as a typical example of its genre, with some appreciation for its brisk pacing and Wayne's early screen presence. Film historians often cite it as an important artifact of Wayne's career development and the poverty row western production model.

What Audiences Thought

The film found its primary audience in small-town theaters and rural areas where westerns were most popular. Matinee audiences of the 1930s would have appreciated its straightforward action and clear morality play. Modern audiences discovering it through public domain compilations generally find it charming as a time capsule of 1930s B-movie production, though it lacks the sophistication of later westerns.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Standard B-western conventions of the 1930s

- Earlier silent western plot structures

- Tom Mix western formula

This Film Influenced

- Subsequent Lone Star John Wayne westerns

- Later B-western revenge plots

- Public domain western compilation films

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in complete form and is in the public domain. Multiple copies exist in various archives, though quality varies due to the cheap original film stock used in production. Some versions show deterioration common to poverty row films of the era.