Scaramouche

"He was a man of the people - a clown of the court - a lover of two women - and the sword of France!"

Plot

Andre-Louis Moreau, a young law student in pre-revolutionary France, witnesses his best friend Philippe de Vilmorin killed by the aristocratic Marquis de la Tour d'Azyr during a duel. Vowing revenge, Moreau becomes an outlaw and joins the revolutionary movement, adopting the disguise of Scaramouche, a clown character in a traveling theater troupe. Using his theatrical persona as cover, he infiltrates aristocratic circles while organizing resistance against the oppressive nobility. Moreau becomes entangled in a complex love triangle with Aline de Kercadiou, his childhood sweetheart, and Lenore, the beautiful actress who helps him maintain his disguise. As the French Revolution begins to brew, Moreau must balance his quest for personal vengeance with his growing commitment to the revolutionary cause, ultimately facing the man who killed his friend in a climactic duel.

About the Production

The film featured elaborate sets designed to recreate 18th-century France, including detailed theater interiors and aristocratic ballrooms. Director Rex Ingram insisted on authenticity, hiring historical consultants and period costume experts. The sword fighting sequences were choreographed by fencing master Fred Cavens, who trained the actors extensively. The production took over six months to complete, unusually long for the era, due to Ingram's perfectionism and the complexity of the action sequences.

Historical Background

Released in 1923, 'Scaramouche' emerged during the golden age of silent cinema and the Roaring Twenties, a period of artistic experimentation and economic prosperity in America. The film's themes of class struggle and revolution resonated with post-World War I audiences who were witnessing social upheaval and political change across Europe. Hollywood was establishing itself as the global center of film production, with studios like MGM investing heavily in lavish historical epics. The film's release coincided with the growing popularity of swashbuckling adventures, which became a defining genre of the era. The story's setting in pre-revolutionary France also appealed to American audiences' fascination with European history and aristocracy, while the revolutionary themes reflected contemporary political tensions in post-war Europe.

Why This Film Matters

'Scaramouche' represents a pinnacle of silent era filmmaking, particularly in the adventure and swashbuckling genres. The film helped establish Ramon Novarro as one of the era's major stars, demonstrating that Latin actors could achieve leading man status in Hollywood. Its success demonstrated the commercial viability of historical epics and influenced the production of similar films throughout the 1920s. The film's elaborate sword fighting sequences set a new standard for action choreography in cinema, influencing countless later films in the swashbuckling genre. The movie also exemplified the artistic possibilities of silent storytelling, using visual techniques, expressive acting, and musical accompaniment to create emotional depth without dialogue. Its preservation and continued study make it an important document of silent era filmmaking techniques and storytelling methods.

Making Of

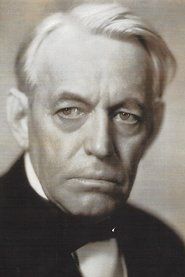

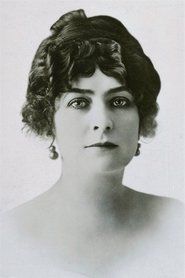

The production was marked by Rex Ingram's meticulous attention to detail and demanding directing style. He insisted on authentic period costumes and props, many of which were imported from Europe. The relationship between Ingram and his wife Alice Terry was well-known in Hollywood, and their professional collaboration was considered one of the most successful director-actor partnerships of the silent era. Ramon Novarro, who was still relatively new to leading roles, underwent extensive preparation for the part, including learning fencing and studying Commedia dell'arte techniques for his clown character. The film's elaborate sword fighting sequences were revolutionary for their time, featuring dynamic camera movements and editing techniques that enhanced the action. Ingram pioneered the use of multiple cameras for complex scenes, allowing for more dynamic editing in the final film.

Visual Style

The cinematography, credited to John F. Seitz, was groundbreaking for its time, featuring innovative camera movements and lighting techniques that enhanced the film's dramatic impact. Seitz employed dramatic lighting contrasts to create mood and atmosphere, particularly in the theater and ballroom scenes. The sword fighting sequences utilized dynamic camera angles and movements that were unusual for the period, creating a sense of immediacy and excitement. The film's visual style combined realistic period detail with romanticized compositions, creating an idealized vision of 18th-century France. Seitz's work on the film demonstrated the artistic possibilities of cinematography beyond simple documentation, using the camera as an active storytelling tool.

Innovations

The film featured several technical innovations that were advanced for its time. The sword fighting sequences utilized pioneering editing techniques to create rhythmic action and tension. The production employed elaborate matte paintings and miniature effects to create convincing historical settings. The makeup effects for Novarro's transformation into Scaramouche were particularly sophisticated for the period. The film's use of multiple cameras for complex scenes allowed for more dynamic editing possibilities. The lighting techniques developed for the film influenced cinematography throughout the 1920s. The movie's preservation of visual quality across its lengthy runtime demonstrated advances in film stock and processing techniques.

Music

As a silent film, 'Scaramouche' was originally accompanied by a musical score compiled from classical pieces and original compositions. The suggested score included works by composers such as Beethoven, Mozart, and contemporary silent film composers. The music was carefully synchronized with the on-screen action, with different themes representing the various characters and emotional states. The theater scenes featured period-appropriate musical selections that enhanced the authenticity of the setting. Modern restorations of the film have been accompanied by newly composed scores by contemporary silent film musicians, maintaining the tradition of live musical accompaniment that was essential to the silent film experience.

Famous Quotes

Intercards: 'He who laughs last laughs best!'

Intercards: 'The sword is the argument of kings!'

Intercards: 'In the theater of life, we all play our parts!'

Intercards: 'Revenge is a dish best served cold!'

Memorable Scenes

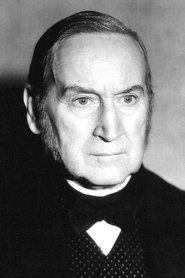

- The extended sword fight sequence between Novarro and Lewis Stone, considered one of the greatest sword fights in silent cinema

- Novarro's transformation scene where he applies his clown makeup and adopts the Scaramouche persona

- The theater performance where Scaramouche first appears before the aristocratic audience

- The final duel on the cliffs overlooking the sea, combining spectacular scenery with intense action

- The ballroom scene where political tensions erupt into violence, showcasing the film's elaborate production design

Did You Know?

- Ramon Novarro performed his own stunts and sword fighting sequences after intensive training with fencing master Fred Cavens

- The film was based on Rafael Sabatini's 1921 novel of the same name, which was a bestseller at the time

- Director Rex Ingram and star Alice Terry were married in real life, making this their fourth collaboration

- The famous sword fight sequence was shot over three weeks and required over 3,000 feet of film

- The film's success helped establish Ramon Novarro as MGM's top male star after Rudolph Valentino's death

- The theater scenes were filmed in an actual theater that was specially constructed for the production

- The film was one of the most expensive productions of 1923, with costumes alone costing over $50,000

- Novarro's transformation from law student to clown required extensive makeup sessions lasting up to three hours

- The film's title comes from the Italian stock character Scaramouche, a roguish clown who traditionally wears a black mask

- The movie was so successful that it led to a sequel, 'The Beloved Rogue' (1927), also starring Novarro

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised 'Scaramouche' as one of the finest films of 1923, with particular acclaim for Rex Ingram's direction and the film's visual splendor. The New York Times called it 'a masterpiece of cinematic art' and praised Novarro's performance as 'both charismatic and deeply moving.' Modern critics continue to recognize the film as a classic of the silent era, with particular appreciation for its technical achievements and influence on the swashbuckling genre. The film is often cited as one of the best adaptations of Sabatini's work and a high point of Novarro's career. Film historians have noted the movie's sophisticated narrative structure and its effective use of visual storytelling techniques that were innovative for the time.

What Audiences Thought

The film was enormously popular with audiences upon its release, becoming one of the biggest box office hits of 1923. Movie theaters reported record attendance, with many venues running the film for extended periods due to demand. Audiences particularly responded to Novarro's charismatic performance and the thrilling sword fighting sequences. The film's romantic elements and themes of justice and revenge resonated strongly with contemporary viewers. Its success led to increased demand for historical adventure films and helped cement Novarro's status as a major box office draw. The movie's popularity endured through multiple re-releases throughout the 1920s and was frequently shown in revival houses during the 1960s and 1970s when interest in silent films experienced a resurgence.

Awards & Recognition

- Photoplay Magazine Medal of Honor (1923) - Winner

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The Three Musketeers (1921)

- Robin Hood (1922)

- The Mark of Zorro (1920)

- Works of Rafael Sabatini

- Commedia dell'arte traditions

- French historical literature

This Film Influenced

- The Prisoner of Zenda (1922)

- The Sea Hawk (1924)

- The Thief of Bagdad (1924)

- The 1952 sound remake of Scaramouche

- The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938)

- The Princess Bride (1987)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved in the Library of Congress and has been restored by several archives including the Museum of Modern Art. While some deterioration is evident due to the film's age, it remains largely complete and viewable. A restored version was released on Blu-ray by Kino Lorber in 2019, featuring a new musical score. The preservation status is considered good for a film of its vintage, with multiple copies existing in various film archives worldwide.