Sons of Ingmar

Plot

Sons of Ingmar follows the story of Ingmar Ingmarsson, a respected farmer in a small Swedish village who becomes entangled in a conflict between traditional rural life and a growing religious revival movement. When a charismatic preacher arrives and begins converting villagers to a fundamentalist sect, Ingmar finds himself at odds with his own son who has joined the movement. The film explores the devastating impact of religious fanaticism on family bonds and community cohesion, culminating in Ingmar's tragic struggle to maintain his farm and family unity. As tensions escalate between the converted and traditional villagers, Ingmar must confront both external threats to his livelihood and internal conflicts within his household.

About the Production

The film was shot entirely on location in Sweden during the summer of 1918. Director Victor Sjöström insisted on authentic rural settings and used local villagers as extras to enhance the film's realism. The production faced challenges with weather conditions, as the Swedish summer was unusually rainy, causing delays in outdoor shooting. Sjöström, known for his perfectionism, required multiple takes for emotional scenes, which was unusual for the period.

Historical Background

Sons of Ingmar was produced during the golden age of Swedish cinema (1917-1924), when Swedish films gained international recognition for their artistic quality and technical innovation. The film emerged in post-World War I Europe, a period when audiences were seeking films that addressed spiritual and moral questions. Sweden remained neutral during WWI, which allowed its film industry to flourish while other European cinema struggled. The early 1920s saw Swedish films, particularly those directed by Victor Sjöström and Mauritz Stiller, achieving critical acclaim and commercial success internationally. This period also coincided with the rise of narrative complexity in cinema, moving away from simple melodramas toward more psychologically sophisticated storytelling.

Why This Film Matters

Sons of Ingmar represents a pivotal moment in Swedish cinema's transition from simple melodramas to complex psychological dramas. The film's exploration of religious conflict and rural life captured the tensions in Swedish society between traditional values and modernization. Its success helped establish Swedish cinema's international reputation for artistic excellence and influenced the development of narrative cinema worldwide. The film's naturalistic acting style and use of authentic locations set new standards for cinematic realism. Its adaptation of Nobel Prize-winning literature also elevated the cultural status of cinema as an art form worthy of literary adaptation. The film's themes of religious fundamentalism and community division remain relevant, making it a precursor to later films exploring similar social conflicts.

Making Of

Victor Sjöström approached this adaptation with meticulous attention to detail, spending months researching rural Swedish life of the 1880s. He insisted on authentic costumes and props, many of which were borrowed from local museums. The casting process was rigorous, with Sjöström conducting extensive screen tests - an uncommon practice at the time. The relationship between Sjöström and author Selma Lagerlöf was collaborative, with Lagerlöf visiting the set multiple times to ensure the adaptation remained faithful to her vision. The film's production coincided with the Spanish flu pandemic, which created additional challenges for the cast and crew. Sjöström's directing style was revolutionary for the period, often using natural lighting and encouraging actors to deliver subtle, naturalistic performances rather than the exaggerated acting typical of silent films.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Julius Jaenzon was groundbreaking for its time, featuring innovative use of natural light and deep focus compositions. Jaenzon employed location shooting to capture the stark beauty of the Swedish landscape, using the environment to reflect the characters' emotional states. The film's visual style emphasized contrast between light and shadow to underscore the moral and spiritual conflicts in the narrative. Jaenzon experimented with camera movement, including subtle tracking shots that were technically advanced for 1919. The cinematography also featured carefully composed group scenes that utilized depth of field to create complex visual narratives within single frames.

Innovations

The film pioneered several technical innovations that influenced subsequent cinema. Sjöström employed advanced editing techniques, including cross-cutting between parallel action sequences to build dramatic tension. The production utilized newly developed panchromatic film stock, which allowed for more accurate representation of colors in black and white photography. The film's soundstage construction techniques allowed for more elaborate interior scenes than typical of the period. The use of multiple cameras for certain scenes enabled more dynamic editing possibilities. The film's special effects, while subtle, included innovative matte paintings and composite shots that enhanced the visual storytelling.

Music

As a silent film, Sons of Ingmar originally featured live musical accompaniment that varied by theater. In Sweden, it was typically accompanied by piano or organ music based on cue sheets provided by the studio. The musical selections often included Swedish folk melodies and classical pieces that complemented the film's emotional arc. Modern restorations have featured newly composed scores by contemporary musicians specializing in silent film accompaniment. The original Swedish cue sheets emphasized minor key compositions for dramatic scenes and folk-inspired melodies for rural sequences.

Famous Quotes

'Faith can be both salvation and destruction,' - Ingmar Ingmarsson

'When the spirit moves, the heart must follow,' - The Preacher

'Some wounds cannot be healed by prayer alone,' - Village Elder

'The soil remembers what the people forget,' - Ingmar Ingmarsson

Memorable Scenes

- The climactic confrontation between Ingmar and his son in the church during the revival service, where the camera uses deep focus to capture both characters' emotional turmoil while showing the divided congregation

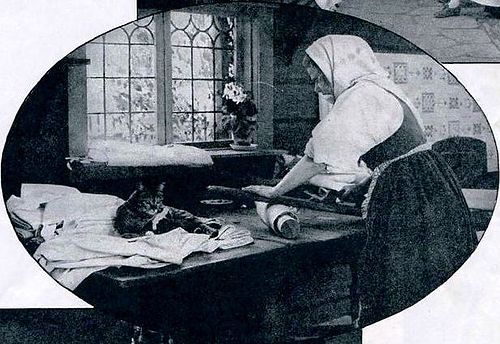

- The opening sequence showing the Swedish harvest with villagers working together, establishing the community's traditional way of life before the religious conflict begins

- The night scene where Ingmar walks alone through the snow-covered fields, contemplating his family's future, using silhouette and natural moonlight for dramatic effect

Did You Know?

- This was the first part of a two-part adaptation of Selma Lagerlöf's novel 'Jerusalem', with the second part being 'Karin Ingmarsdotter' released later in 1919

- Director Victor Sjöström not only directed but also starred in the lead role, a common practice in early Swedish cinema

- The film was based on Nobel Prize-winning author Selma Lagerlöf's work, who was highly involved in the adaptation process

- Sjöström and Lagerlöf had previously collaborated on 'The Outlaw' (1918) and 'The Phantom Carriage' (1921)

- The film's original Swedish title was 'Ingmarssönerna'

- Harriet Bosse, who played the female lead, was a famous stage actress and former wife of playwright August Strindberg

- The film was considered lost for decades before a print was discovered in the 1970s in the Soviet film archives

- Sjöström used innovative deep focus techniques that were ahead of their time

- The religious themes in the film caused some controversy upon its release in deeply religious rural Sweden

- The film was one of the most expensive Swedish productions of its time, utilizing over 500 extras for crowd scenes

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film for its artistic ambition and emotional depth. Swedish newspapers hailed it as a masterpiece of national cinema, with particular acclaim for Sjöström's dual role as director and actor. International critics, especially in France and Germany, noted the film's sophisticated visual style and psychological complexity. Modern film historians consider Sons of Ingmar one of the most important Swedish silent films, citing its influence on subsequent European cinema. The film is frequently referenced in academic studies of early cinema as an example of the transition from theatrical to cinematic storytelling. Critics have particularly praised Sjöström's innovative use of landscape as a narrative element and the film's nuanced treatment of religious themes.

What Audiences Thought

The film was a commercial success in Sweden, drawing large audiences in Stockholm and other major cities. Rural audiences had mixed reactions, with some finding the depiction of religious conflict uncomfortable or controversial. The film's emotional power resonated with post-war audiences seeking meaningful narratives. International audiences, particularly in Germany and France, embraced the film's artistic qualities, helping establish Swedish cinema's reputation abroad. The film's success led to increased demand for Swedish films internationally and inspired other countries to seek distribution rights for Swedish productions. Contemporary audience reactions were documented in newspaper reviews, with many viewers praising the film's authenticity and emotional impact.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Selma Lagerlöf's novel Jerusalem

- Swedish literary tradition

- Ibsen's dramatic works

- D.W. Griffith's narrative techniques

- German Expressionist visual style

- Nordic folklore traditions

This Film Influenced

- Karin Ingmarsdotter (1920)

- The Phantom Carriage (1921)

- Gosta Berlings Saga (1924)

- The Wind (1928)

- The Seventh Seal (1957)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was believed lost for decades but a complete print was discovered in the Gosfilmofond archive in Moscow in the 1970s. The Swedish Film Institute has since restored the film using this and other surviving elements. A digitally restored version was released in 2011 as part of the Victor Sjöström collection. The restoration process involved frame-by-frame digital cleaning and color correction based on original production notes. The film is now preserved in the archives of the Swedish Film Institute and is available for scholarly study.