St. Jorgen's Day

"A biting satire of faith and fraud in the age of exploitation"

Plot

In this Soviet satirical comedy, corrupt priests, stock market speculators, and police officials conspire to exploit pilgrims who have come to venerate supposed relics of a Christ-like figure. Two professional con men, Khrushchev and Skorokhodov, devise an elaborate scheme to profit from the religious fervor by staging the resurrection of a fake saint. The film follows their increasingly absurd attempts to maintain the deception while navigating between the greedy officials and the genuinely believing masses. As their charade grows more elaborate and dangerous, the con men find themselves trapped in their own web of deception, leading to a chaotic climax that exposes both religious superstition and capitalist exploitation.

About the Production

The film was produced during the height of Stalin's anti-religious campaign, making its satirical critique of religious institutions particularly bold for its time. The production faced significant challenges from Soviet censorship authorities who were concerned about the film's potential to offend religious believers while also questioning whether it went far enough in its anti-religious message. Director Porfiri Podobed had to make multiple revisions to satisfy both the artistic committee and political censors.

Historical Background

The film was produced during the First Five-Year Plan (1928-1932), a period of rapid industrialization and cultural transformation in the Soviet Union. Stalin's government had intensified anti-religious campaigns, closing churches and promoting atheism through propaganda. Cinema was seen as a crucial tool for spreading socialist values and attacking 'bourgeois' institutions like organized religion. The League of the Militant Godless, a powerful organization with millions of members, actively promoted anti-religious art and literature. Against this backdrop, 'St. Jorgen's Day' represented both the state's ideological goals and the Soviet film industry's desire to create popular entertainment that could compete with foreign imports. The film's satirical approach to religious exploitation reflected the broader Soviet critique of religion as both superstition and a tool of class oppression.

Why This Film Matters

'St. Jorgen's Day' occupies an important place in Soviet cinema history as one of the first major film comedies to directly address religious themes through satire. It demonstrated that Soviet cinema could tackle controversial subjects while maintaining popular appeal, paving the way for future satirical works. The film's blend of social commentary and slapstick comedy influenced subsequent Soviet comedy directors, including Grigory Aleksandrov and Leonid Gaidai. Its critique of religious exploitation resonated with the Soviet state's anti-religious policies while also offering a more nuanced take on the nature of belief and deception. The film has been studied by film scholars as an example of how Soviet cinema navigated the delicate balance between ideological messaging and entertainment value during the early Stalinist period.

Making Of

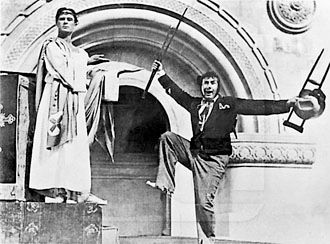

The production of 'St. Jorgen's Day' took place during a tumultuous period in Soviet cinema, as the industry was transitioning from silent films to sound. Director Podobed, working with cinematographer Vladimir Taburin, experimented with early sound recording techniques while maintaining the visual comedy style established in the silent era. The casting of Igor Ilyinsky, already a major star, was seen as risky given the film's controversial subject matter. The production team built elaborate sets representing a religious shrine and pilgrimage site, which were designed to look authentic enough to fool the film's 'believing' characters while appearing obviously fake to the audience. The famous resurrection sequence required multiple takes and innovative camera tricks, including hidden wires and carefully timed smoke effects. The film's editing was particularly praised for its rapid-fire comedy timing, influenced by both Soviet montage theory and American slapstick comedies that were still being screened in the USSR at the time.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Vladimir Taburin demonstrated the sophisticated visual style developing in Soviet cinema during the transition to sound. Taburin employed dynamic camera movements and unusual angles to enhance the comedy, particularly during the chaotic pilgrimage scenes. The film made effective use of deep focus to create visual gags with multiple layers of action happening simultaneously. The resurrection sequence featured innovative lighting effects and camera tricks that created an otherworldly atmosphere while maintaining the comedic tone. Taburin's work showed the influence of both Soviet montage theory and German expressionist cinema, resulting in a visually rich film that stood out among contemporary Soviet productions.

Innovations

The film was notable for its early use of sound technology in Soviet cinema, representing one of the first successful attempts to combine synchronized music with visual comedy. The production team developed new techniques for recording sound during complex crowd scenes, a significant challenge in early sound recording. The special effects used for the resurrection sequence, including hidden wires and smoke machines, were considered technically advanced for Soviet cinema in 1930. The film's editing techniques, particularly its rapid cutting during comedy sequences, influenced the development of Soviet film comedy pacing. The production also pioneered methods for shooting large crowd scenes with synchronized sound, techniques that would become standard in later Soviet epics.

Music

As an early sound film, 'St. Jorgen's Day' featured a synchronized musical score composed by Dmitri Kabalevsky in one of his earliest film assignments. The music blended traditional Russian folk melodies with modernist orchestral techniques, creating a sound that was both familiar and contemporary to Soviet audiences. The film used diegetic music extensively, with the religious scenes featuring distorted church music that emphasized their fraudulent nature. The comedy sequences were accompanied by lively, jazz-influenced rhythms that reflected the Soviet fascination with Western popular music during the NEP period. The sound effects were particularly innovative for their time, using exaggerated noises to enhance the physical comedy.

Famous Quotes

A fool and his money are soon parted, especially when God is involved.

Miracles are expensive, but faith is priceless - that's why we sell it so cheap.

In the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king, and in the land of believers, the cleverest con man is a saint.

Religion is the best business - your customers never demand their money back, even when the product fails to deliver.

Memorable Scenes

- The elaborate resurrection sequence where the fake saint dramatically rises from his coffin, complete with smoke effects and divine lighting, while the con men struggle to maintain their composure and the crowd reacts with alternating awe and suspicion.

- The chaotic pilgrimage scene where thousands of extras create a massive crowd, all pushing and shoving to get closer to the relics, while the con men work their way through the masses collecting donations.

- The climactic exposure scene where the police, priests, and stock market officials all turn on each other when the fraud is revealed, creating a slapstick free-for-all that satirizes institutional corruption.

- The opening scene where the two con men first devise their plan, using elaborate charts and calculations to determine exactly how much money they can make from faking a miracle.

Did You Know?

- The film was one of the first Soviet comedies to directly tackle religious themes following the state's intensified anti-religious campaigns of the late 1920s

- Director Porfiri Podobed was primarily known as an actor before transitioning to directing, and this was one of his few directorial efforts

- The character names Khrushchev and Skorokhodov were chosen for their comedic value, with 'Skorokhodov' roughly translating to 'quick-walker'

- The film was temporarily banned in several Soviet republics for being 'too subtle' in its anti-religious message

- Igor Ilyinsky, one of Soviet cinema's biggest comedy stars, performed many of his own stunts in the film

- The fake saint's resurrection scene required elaborate special effects that were innovative for Soviet cinema of 1930

- The film's original title was changed several times during production to avoid offending religious sensitivities while maintaining the satirical tone

- Many of the supporting cast were actual theater actors from Moscow's Satire Theatre, brought in specifically for their comedic timing

- The film was shot during the transition from silent to sound cinema, resulting in a hybrid production with both synchronized music and intertitles

- Contemporary Soviet critics praised the film for its 'progressive social content' but criticized its 'bourgeois entertainment value'

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics gave the film mixed reviews. Pravda praised its 'courageous attack on religious superstition' but warned that 'the comedy must not obscure the serious ideological message.' Kino magazine criticized what it called the film's 'excessive entertainment value' that might distract audiences from its educational purpose. International critics, when the film was shown abroad in limited screenings, noted its sophisticated visual comedy but found the anti-religious message heavy-handed. Modern film historians have reevaluated the work more positively, recognizing it as a technically accomplished comedy that successfully navigated the complex ideological requirements of its time while maintaining artistic merit.

What Audiences Thought

The film was popular with Soviet audiences, particularly in urban centers where anti-religious sentiment was stronger. Movie theaters reported good attendance, especially among young workers and students who appreciated both the comedy and the film's progressive message. However, in rural areas with stronger religious traditions, the film sometimes sparked controversy, with some local officials reporting that it 'offended the sensibilities of believing peasants.' Despite these regional variations, the film was generally considered a commercial success by Soviet cinema standards of the period and helped establish Igor Ilyinsky as one of the most popular comedy actors in the USSR.

Awards & Recognition

- None formally recorded - Soviet award systems were not yet fully established in 1930

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Soviet montage theory

- German expressionist cinema

- American slapstick comedy

- Charlie Chaplin's social satires

- Buster Keaton's visual comedy

- Eisenstein's theoretical writings on film

- Meyerhold's theatrical techniques

This Film Influenced

- Volga-Volga (1938)

- The Bright Path (1940)

- Carnival Night (1956)

- The Diamond Arm (1969)

- Ivan Vasilievich Changes Profession (1973)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is partially preserved with some degradation. A restored version was completed by Gosfilmofond in the 1970s, though some scenes remain incomplete. The original nitrate negatives suffered damage during World War II, but a complete print exists in the Russian State Archive of Film and Photo Documents. The film has been digitized and is occasionally shown at classic film festivals and Soviet cinema retrospectives.