The City without Jews

"A prophetic vision of hatred and its consequences"

Plot

In the fictional Republic of Utopia (representing Vienna), severe economic crisis leads the government to scapegoat the Jewish population for all social and economic problems. The parliament passes the 'Expropriation Law,' forcing all Jews to leave the country. Leo Strakosch, a Jewish man engaged to Councilor Linder's daughter, is among those exiled. Determined to expose the prejudice and demonstrate the Jews' vital contribution to society, Leo returns to Utopia in disguise with a false identity. As the economy continues to collapse without its Jewish citizens, Leo works to reveal the truth and convince the population of their terrible mistake, ultimately leading to the Jews being welcomed back in the film's optimistic conclusion.

About the Production

The film was produced during a period of rising antisemitism in Austria and Germany. Director H.K. Breslauer made significant changes from Hugo Bettauer's original novel, including changing the setting from Vienna to the fictional 'Utopia' and adding a happy ending where the Jews are welcomed back, unlike the novel's more ambiguous conclusion. The production faced immediate controversy and threats from nationalist groups.

Historical Background

The film was produced during the early 1920s, a period of extreme political and economic instability in Austria and Germany following World War I. Hyperinflation, unemployment, and social unrest created fertile ground for nationalist and antisemitic movements. The Nazi party was gaining strength in Germany, and similar ideologies were spreading in Austria. Bettauer's novel and Breslauer's film adaptation were direct responses to this rising tide of antisemitism. The film's release came just months before Hitler's failed Beer Hall Putsch in 1923 and during the period when antisemitic political parties were gaining electoral support throughout Central Europe. The film served as both warning and protest against the dangerous ideologies that would soon consume Europe.

Why This Film Matters

The City without Jews stands as one of cinema's earliest and most prescient warnings against antisemitism and totalitarianism. Its rediscovery has revealed it as a remarkably prophetic work that anticipated the Holocaust by over a decade. The film demonstrates how cinema was used as early political commentary and social critique. Its restoration and exhibition in the 21st century have sparked new discussions about the role of art in confronting hatred and prejudice. The film serves as crucial historical documentation of the early warning signs that preceded the Nazi rise to power, making it not just a cinematic work but an important historical document that continues to resonate in contemporary discussions about intolerance and xenophobia.

Making Of

Director H.K. Breslauer, himself of Jewish descent, took significant personal risk in adapting Bettauer's controversial novel. The production faced harassment from nationalist groups during filming in Vienna. Breslauer made the controversial decision to change the novel's ending, providing an optimistic conclusion where the citizens of Utopia realize their mistake and welcome the Jewish population back. This change was likely made to make the film more palatable to audiences and censors. The casting of Johannes Riemann as Leo Strakosch was significant, as he was a popular leading man of the era. The film used location shooting in Vienna to create an authentic atmosphere, though the city was renamed 'Utopia' in the intertitles.

Visual Style

The film's cinematography by Hugo Eywo utilized typical silent era techniques but with remarkable compositional sophistication. The visual contrast between the prosperous scenes with the Jewish population and the bleak, impoverished streets after their expulsion creates powerful visual commentary. Eywo employed dramatic lighting and framing to emphasize the emotional states of characters and the social atmosphere. The film uses location shooting effectively to create an authentic urban environment that serves as more than mere backdrop.

Innovations

While not technically innovative in the manner of German Expressionist cinema, the film demonstrated sophisticated use of montage and cross-cutting to create social commentary. The film's preservation and restoration using digital technology represents a significant technical achievement in film archaeology, allowing a work thought lost for over 80 years to be seen again. The restoration team used multiple sources to create the most complete version possible.

Music

As a silent film, it would have been accompanied by live musical performance in theaters. The 2017 restoration features a newly commissioned score by Austrian composer Olga Neuwirth, which incorporates elements of 1920s popular music, classical motifs, and modern electronic sounds to bridge the historical and contemporary aspects of the film. Original theater accompaniment would have varied by venue, ranging from solo piano to full orchestra.

Famous Quotes

When the Jews leave, prosperity leaves with them

We have driven out our best doctors, our finest artists, our most successful businessmen

In removing the problem, we have removed the solution

Utopia without Jews is not utopia at all

Memorable Scenes

- The parliament scene where the Expropriation Law is passed, showing the enthusiastic support for antisemitic legislation

- The mass departure of Jewish families from Utopia, with intertitles listing their professions and contributions

- Leo Strakosch's disguised return to the city, showing the dramatic changes and deterioration

- The final scene where the citizens realize their mistake and welcome the Jewish population back

Did You Know?

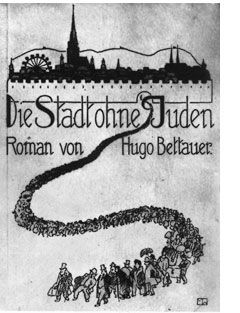

- The film was based on Hugo Bettauer's controversial 1922 novel 'Die Stadt ohne Juden'

- Hugo Bettauer was murdered by a Nazi party member in March 1925, partly due to the controversy surrounding this work

- The film was considered lost for over 80 years until a complete copy was found at a Dutch film archive in 2015

- The film was banned in several German cities including Munich and Nuremberg upon its release

- It was one of the first cinematic works to explicitly address and warn against antisemitism

- Actor Hans Moser, who played a supporting role, would become one of Austria's most beloved comic actors

- The film's happy ending was a significant departure from Bettauer's novel, which ended more ambiguously

- The original Austrian film negative was believed destroyed during World War II

- The restored version premiered at the Berlin International Film Festival in 2017

- The film accurately predicted many events that would occur under Nazi rule a decade later

What Critics Said

Upon its 1924 release, the film received mixed reviews, with progressive critics praising its courage and social commentary, while conservative and nationalist publications condemned it as 'Jewish propaganda.' The film faced immediate censorship in several German cities. Contemporary critics reviewing the restored version have hailed it as a lost masterpiece of political cinema and a chillingly accurate prediction of the horrors to come. Modern film scholars consider it one of the most important Austrian films of the silent era and a crucial document of its time.

What Audiences Thought

Initial audience reception in Austria was generally positive among liberal and intellectual circles, but the film faced protests and demonstrations from nationalist groups. In cities where it was banned, underground screenings attracted politically aware audiences. Following its 2017 restoration, the film has been shown to enthusiastic audiences at film festivals worldwide, with many viewers struck by its contemporary relevance and disturbing accuracy in predicting future events.

Awards & Recognition

- No major awards documented - the film was too controversial for award consideration at the time

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Hugo Bettauer's novel 'Die Stadt ohne Juden'

- German Expressionist cinema

- Social realist literature of the 1920s

- Political theater of the Weimar Republic

This Film Influenced

- Numerous films addressing antisemitism and prejudice

- Political cinema of the 1930s

- Holocaust films of later decades

- Contemporary films about immigration and xenophobia

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was considered lost for over 80 years. A complete 35mm copy was discovered in 2015 at the Dutch Film Museum in Amsterdam. The film has been digitally restored by the Filmarchiv Austria and premiered in its restored version at the Berlin International Film Festival in 2017. The restoration represents one of the most significant film archaeology discoveries of recent years.