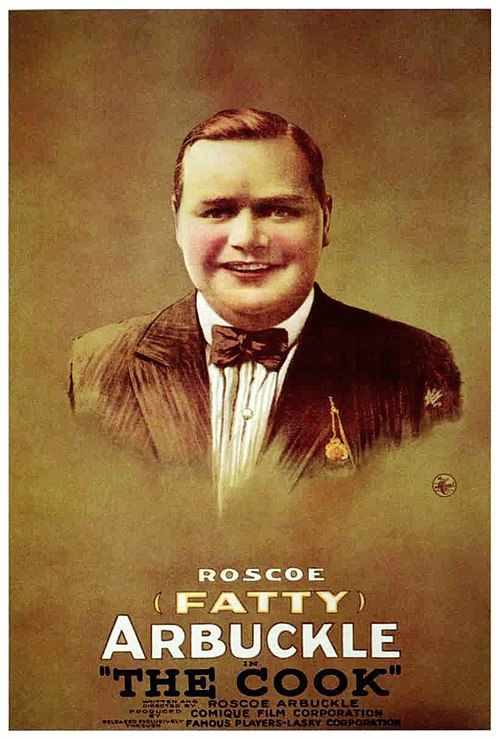

The Cook

"Where the Kitchen is a Battlefield and the Waiter is a Walking Disaster!"

Plot

In 'The Cook,' chaos reigns supreme at a bustling oceanside restaurant where Fatty Arbuckle portrays an eccentric chef and Buster Keaton plays a perpetually flustered waiter. Their attempts at creating greater efficiency through various schemes and inventions backfire spectacularly, resulting in a cascade of comedic disasters that threaten to destroy the entire establishment. The situation escalates dramatically when a notorious robber arrives, adding criminal complications to the already chaotic kitchen environment. As the robber attempts to hold up the restaurant, Arbuckle and Keaton must overcome their own incompetence to save the day, leading to a series of increasingly elaborate physical comedy sequences. The film culminates in a madcap chase scene that showcases the performers' incredible athletic abilities and timing, ultimately resolving with the robber captured and the restaurant in even greater disarray than when it began.

About the Production

This film was produced during Arbuckle's most prolific and successful period at Comique Film Corporation, the company he formed with Joseph Schenck. The restaurant set was an elaborate construction that allowed for multiple levels of physical comedy, including a functional kitchen with real cooking equipment that added authenticity to the chaos. The ocean backdrop was achieved through painted backdrops and clever set design, typical of studio productions of the era. The film featured innovative camera techniques for the time, including low-angle shots during the kitchen chaos sequences.

Historical Background

The Cook was produced during the final year of World War I, a time when American audiences were seeking escapist entertainment to distract from the global conflict. The film industry was undergoing significant changes in 1918, with the star system becoming firmly established and studios like Paramount and Fox beginning to dominate production. Silent comedy had reached its artistic peak, with performers like Charlie Chaplin, Harold Lloyd, and Arbuckle developing distinct comedic personas. The film reflected the post-Progressive Era fascination with efficiency and scientific management, parodying contemporary attempts to streamline restaurant operations. The ocean setting also tapped into the growing popularity of seaside resorts among the American middle class, making the chaos particularly relatable to contemporary audiences.

Why This Film Matters

'The Cook' represents a crucial transitional moment in American comedy cinema, marking the period when Buster Keaton was evolving from Arbuckle's supporting player to a major comedic force in his own right. The film's sophisticated physical comedy and multi-layered gags influenced generations of comedians and filmmakers, establishing techniques that would become staples of cinematic comedy. Its restaurant setting created a template for countless future comedy films and television shows set in chaotic food service environments. The collaboration between Arbuckle and Keaton demonstrated the potential of comedic partnerships, influencing later duos like Laurel and Hardy and Abbott and Costello. The film also exemplifies the golden age of American silent comedy, showcasing the art form at its most inventive and physically demanding.

Making Of

The production of 'The Cook' was marked by the incredible creative chemistry between Arbuckle and Keaton, who had developed a near-telepathic understanding of each other's comedic timing. Arbuckle, as director, encouraged improvisation and allowed Keaton significant creative input in developing gags. The kitchen sequences required extensive coordination between the actors, camera operators, and prop handlers, as many gags involved precise timing with falling objects, splashing liquids, and collapsing structures. Keaton's famous 'stone face' expression was developed during these collaborations, serving as a perfect counterpoint to Arbuckle's more emotive performance style. The film's robber character, played by Al St. John, was added during production to provide a narrative framework for the increasingly elaborate physical comedy sequences. The cast and crew often worked 12-hour days to complete the complex stunt sequences, with Arbuckle personally performing many of the most dangerous stunts despite his large frame.

Visual Style

The cinematography in 'The Cook' was handled by George Peters, who employed innovative techniques to capture the rapid-fire comedy sequences. The film uses wide shots effectively to establish the restaurant's spatial relationships, allowing audiences to track multiple gags occurring simultaneously. Low-angle shots during the kitchen chaos emphasize the scale of the destruction and enhance the physical comedy. The camera work during chase sequences demonstrates remarkable fluidity for the period, with smooth tracking shots that follow the actors through various obstacles. The film makes effective use of depth of field, particularly in scenes where action occurs on multiple planes of the restaurant set. The ocean backdrop is integrated seamlessly through matte shots, creating the illusion of a seaside location.

Innovations

The Cook featured several technical innovations for its time, including complex rigging systems for the elaborate kitchen gags involving falling objects and collapsing structures. The film employed early versions of what would become known as 'slapstick engineering,' with custom-built props designed to fail in specific, comedic ways. The production utilized multiple cameras for certain sequences, allowing for better coverage of complex physical comedy. The restaurant set incorporated hidden mechanisms for various gags, including trap doors and retractable walls. The film's chase sequences demonstrated advanced editing techniques for the period, with rapid cuts that enhanced the sense of chaos and momentum. The production also experimented with speed manipulation in some sequences, slightly undercranking the camera to make the action appear more frantic.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Cook' originally featured live musical accompaniment that varied by theater. Typical scores included popular songs of the era like 'After You've Gone' and 'Oh, You Beautiful Doll,' along with classical pieces adapted for comedic effect. The film's restoration includes a newly composed score by silent film music specialist Rodney Sauer, performed on authentic period instruments. The original cue sheets suggested specific musical moments synchronized with key gags, such as frantic piano music during kitchen disasters and chase scenes. The score emphasized percussion instruments to enhance physical comedy moments, particularly during scenes involving falling objects and collisions.

Famous Quotes

Intertitle: 'Our new system of efficiency will revolutionize the restaurant business!'

Intertitle: 'Help! The kitchen has declared war on the chef!'

Intertitle: 'A waiter's work is never done... especially when he keeps breaking everything!'

Intertitle: 'In this restaurant, even the food fights back!'

Memorable Scenes

- The legendary kitchen chaos sequence where Arbuckle's various efficiency inventions simultaneously malfunction, creating a cascade of flying food, collapsing shelves, and exploding steam pipes that showcases both performers' incredible timing and athletic ability. The scene culminates in Arbuckle becoming entangled in pasta while Keaton attempts to serve customers through the ensuing disaster, creating a perfect storm of visual comedy.

Did You Know?

- This was one of the first films where Buster Keaton received significant screen time alongside Arbuckle, helping establish his persona before he became a solo star.

- The restaurant kitchen set was so elaborate that it took nearly a week to build, featuring working stoves, pipes, and various mechanisms for gags.

- Arbuckle and Keaton performed many of their own stunts, including dangerous falls and acrobatic sequences that would be considered risky even by modern standards.

- The film was shot in just four days, remarkably fast considering the complexity of the physical comedy sequences.

- Al St. John, who plays the robber, was Arbuckle's nephew and a regular collaborator in his films.

- The famous 'keystone cops' style chase at the end was influenced by Mack Sennett's work but elevated by Arbuckle and Keaton's unique physical comedy style.

- The film's success led to increased demand for Keaton in Arbuckle's subsequent pictures.

- Many of the kitchen gags were improvised on set by Arbuckle and Keaton during filming.

- The original nitrate film print was considered lost for decades before being rediscovered in a European archive in the 1970s.

- This was one of the last films Arbuckle made before his contract with Paramount began, marking the end of his independent production period.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised 'The Cook' for its inventive gags and the remarkable chemistry between Arbuckle and Keaton. Variety noted that 'the kitchen sequences alone are worth the price of admission,' while Motion Picture News highlighted the film's 'relentless pace and increasingly hilarious complications.' Modern critics and film historians have come to regard the film as a masterpiece of silent comedy, with many considering it among the best of Arbuckle's directorial efforts. The film is frequently cited in academic studies of silent cinema for its innovative use of physical space and timing. The restoration of the film in the 1990s led to renewed appreciation, with The New York Times calling it 'a perfect example of why Arbuckle and Keaton were considered geniuses of their craft.'

What Audiences Thought

The Cook was enormously popular with audiences upon its release, playing to packed houses in major cities across the United States. Contemporary theater reports indicated that audiences laughed continuously throughout the film, with many scenes requiring multiple viewings to catch all the gags occurring simultaneously. The film's success was particularly notable given its release during the influenza pandemic of 1918, when theater attendance was generally depressed. Audience letters to trade publications frequently mentioned the kitchen scenes as their favorite parts, with many requesting that Arbuckle and Keaton make more films together. The film's popularity contributed significantly to Arbuckle's status as one of the highest-paid stars in Hollywood, earning him an unprecedented $3,000 per week at the time.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Mack Sennett's Keystone comedies

- Charlie Chaplin's early shorts

- French farce traditions

- Vaudeville comedy routines

- Contemporary efficiency movement literature

This Film Influenced

- The General (1926)

- The Gold Rush (1925)

- Modern Times (1936)

- The Restaurant (1934)

- Hell's Kitchen (1939)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The Cook is preserved in its complete form at the Library of Congress and the Museum of Modern Art. The film was restored in 1998 from original nitrate elements discovered in the Czech Film Archive. A digitally remastered version was released in 2015 as part of The Arbuckle-Keaton Collection. The preservation includes original tints and toning that were part of the original release prints.