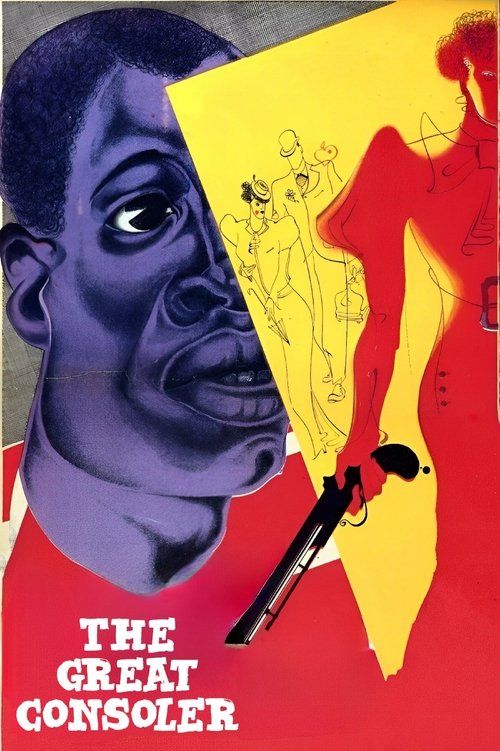

The Great Consoler

Plot

The Great Consoler follows the story of a newspaper journalist who becomes disillusioned with his work and society's expectations. The protagonist struggles with the moral compromises required in his profession and the gap between his artistic ideals and the harsh realities of Soviet life in the early 1930s. Through his journey, the film explores the internal conflict of a creative intellectual trying to find his place in a rapidly changing society that demands conformity. The narrative interweaves personal drama with broader social commentary, showing how the protagonist's attempts to 'console' others through his writing ultimately lead to his own existential crisis. The film culminates in a powerful examination of whether art can truly serve both truth and social progress in an increasingly rigid political environment.

About the Production

The film was shot during a particularly difficult period in Soviet cinema when artistic freedom was increasingly restricted. Kuleshov, known for his pioneering work in film theory and the 'Kuleshov effect,' faced significant challenges getting this personal project approved by Soviet authorities. The production was marked by tensions between Kuleshov's artistic vision and the growing demands for socialist realism in cinema. Alexandra Khokhlova, who starred in the film, was both Kuleshov's wife and his frequent collaborator, bringing a deep understanding of his artistic philosophy to her performance.

Historical Background

The Great Consoler was produced in 1933, during a critical turning point in Soviet cultural and political history. This period marked the consolidation of Stalin's power and the implementation of the first Five-Year Plan, which brought massive industrialization and collectivization to the Soviet Union. The early 1930s also saw the establishment of socialist realism as the official aesthetic doctrine in Soviet arts, effectively ending the experimental avant-garde period of the 1920s. Artists and intellectuals faced increasing pressure to conform to state-sanctioned themes and styles, with dissent often leading to severe consequences. The film emerged during the Great Famine (1932-1933) and the beginning of massive political purges that would later characterize the Stalin era. Against this backdrop, Kuleshov's exploration of the artist's role in society was particularly daring and potentially dangerous. The film's questioning of individual creative freedom versus collective social responsibility reflected the broader tensions between artistic autonomy and political control that defined this period in Soviet history.

Why This Film Matters

The Great Consoler holds a unique place in Soviet cinema history as one of the last films to emerge from the avant-garde tradition before the full imposition of socialist realism. It represents a crucial transitional moment in Soviet cultural history, when experimental filmmakers were forced to adapt to new political realities. The film's exploration of media ethics and the role of the intellectual in society was remarkably prescient, anticipating debates that would continue throughout the 20th century. Kuleshov's incorporation of his theoretical principles into a narrative feature demonstrated the practical application of film theory in ways that influenced subsequent generations of filmmakers. The film also serves as a valuable historical document of the anxieties and dilemmas faced by Soviet artists during this period of political consolidation. Its suppression after release and relative obscurity in subsequent decades make it an important example of the many works that were marginalized or lost during the Stalin era. Today, the film is studied as both a work of art and a historical artifact that illuminates the complex relationship between creativity and political power in the Soviet Union.

Making Of

The making of The Great Consoler was fraught with the political tensions that characterized Soviet cultural life in the early 1930s. Kuleshov, who had been a leading figure in the Soviet avant-garde cinema movement of the 1920s, found himself increasingly at odds with the new aesthetic doctrine of socialist realism being imposed by cultural authorities. The film's production was marked by extensive negotiations with censors, who were concerned about its potentially critical stance toward the role of artists and intellectuals in Soviet society. Kuleshov's wife, Alexandra Khokhlova, played a crucial role not only as the lead actress but also as a creative partner who helped shape the film's complex narrative structure. The cast and crew worked under constant pressure to balance artistic expression with political acceptability. Despite these challenges, Kuleshov managed to incorporate many of his innovative editing techniques and theoretical concepts into the film, creating what many consider his most mature and personal work. The production process itself became a testament to the very themes the film explores - the struggle of the artist to maintain integrity in a demanding political environment.

Visual Style

The cinematography of The Great Consoler demonstrates Lev Kuleshov's mastery of visual storytelling and his innovative approach to film language. The film employs sophisticated use of montage and editing techniques that reflect Kuleshov's theoretical work on the 'Kuleshov effect' - the idea that viewers derive more meaning from the interaction of sequential shots than from a single shot in isolation. The visual style incorporates dramatic lighting contrasts and carefully composed frames that emphasize the psychological states of the characters. Kuleshov uses camera angles and movement to create visual metaphors for the protagonist's internal conflicts and social alienation. The film's visual vocabulary draws from both German Expressionism and Soviet montage theory, creating a distinctive aesthetic that bridges different cinematic traditions. The cinematography also serves the film's thematic concerns, with visual motifs recurring throughout to reinforce ideas about perception, reality, and the nature of artistic creation. Despite the technical limitations of early 1930s Soviet film equipment, the cinematography achieves remarkable visual sophistication and emotional resonance.

Innovations

The Great Consoler represents several important technical achievements in early Soviet cinema. The film showcases Kuleshov's innovative editing techniques, particularly his use of intellectual montage to create complex meanings through the juxtaposition of images. The production demonstrated sophisticated approaches to lighting and camera work that pushed the technical boundaries of what was possible with available equipment. Kuleshov's experiments with focus and depth of field created visual effects that enhanced the film's psychological realism. The film also represents an early successful integration of sound with visual storytelling in Soviet cinema, using audio elements to complement rather than overwhelm the visual narrative. The technical crew developed new methods for recording dialogue in noisy environments, particularly for the newspaper office scenes. The film's special effects, while subtle, demonstrated creative solutions to technical challenges. The production also pioneered techniques for creating realistic urban environments on limited studio sets. These technical innovations not only served the artistic needs of the film but also contributed to the broader development of cinematic technology in the Soviet Union.

Music

The Great Consoler was produced during the transition from silent to sound cinema in the Soviet Union, and it incorporates early sound technology in innovative ways. The film's score combines original musical compositions with popular songs of the period, creating a soundtrack that enhances the emotional and thematic dimensions of the narrative. The use of sound is particularly notable in scenes depicting the newspaper office environment, where the clatter of typewriters and ringing phones create an auditory landscape that emphasizes the mechanical nature of modern journalism. Kuleshov's approach to sound reflects his experimental sensibilities, using audio elements not merely as accompaniment but as integral components of the film's meaning-making apparatus. The soundtrack also includes diegetic music that reflects the cultural tastes of the Soviet intelligentsia in the early 1930s. While the technical quality of the sound recording reflects the limitations of the period, the creative use of audio elements demonstrates Kuleshov's understanding of how sound could enhance cinematic storytelling. The film's audio-visual integration represents an important step in the development of Soviet sound cinema.

Famous Quotes

To console others, one must first understand one's own despair.

The truth is a dangerous thing in the hands of those who cannot handle it.

We write for the masses, but who writes for us?

In a world of headlines, the human heart becomes a footnote.

The artist's greatest crime is not failure, but compromise without conviction.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence in the bustling newspaper office, where the rhythmic clatter of typewriters creates a mechanical symphony that establishes the film's theme of dehumanization in modern media.

- The protagonist's late-night walk through the empty streets of Moscow, beautifully lit to emphasize his isolation and internal struggle.

- The climactic scene where the journalist must choose between publishing a comforting lie or a painful truth, visually represented through contrasting lighting and camera angles.

- The sequence where the protagonist visits a working-class neighborhood, using montage techniques to contrast his privileged perspective with the reality of ordinary Soviet citizens.

Did You Know?

- The Great Consoler was Lev Kuleshov's final feature film as a director, marking the end of his most creative period in cinema.

- The film's title refers to the protagonist's role as a journalist who tries to comfort and console readers through his writing, while personally struggling with despair.

- Kuleshov was one of the first film theorists to systematically study editing and montage, and this film incorporates many of his theoretical principles.

- The film was controversial upon release for its questioning of the artist's role in Soviet society, a topic that was becoming increasingly sensitive under Stalin's regime.

- Alexandra Khokhlova, who played a leading role, was not only Kuleshov's wife but also a prominent film director and theorist in her own right.

- The film was partially inspired by O. Henry's short story 'The Last Leaf,' though Kuleshov significantly adapted the story to fit Soviet context.

- After this film, Kuleshov focused primarily on teaching and writing about film theory rather than directing, partly due to the political climate.

- The film contains one of the earliest Soviet explorations of media ethics and the responsibility of journalists to society.

- Despite its artistic merits, the film was largely suppressed after its initial release and was rarely shown in subsequent decades.

- The production coincided with the first Five-Year Plan period, a time of massive social and economic transformation in the Soviet Union.

What Critics Said

Upon its initial release in 1933, The Great Consoler received mixed reviews from Soviet critics, many of whom were already adapting to the new demands of socialist realism. Some praised Kuleshov's technical mastery and the film's bold thematic concerns, while others criticized it for being too introspective and insufficiently optimistic about Soviet life. The film's questioning of the artist's role was viewed with suspicion by party-aligned critics who preferred more straightforward celebrations of Soviet achievements. In the decades following its release, the film was largely ignored in official Soviet film histories, partly due to its problematic themes and partly because Kuleshov himself had fallen out of favor with the cultural establishment. Western film scholars rediscovered the film in the 1960s and 1970s during the revival of interest in Soviet avant-garde cinema, recognizing it as an important work that bridged the experimental 1920s and the more conformist later periods. Contemporary critics now view the film as a masterpiece of psychological cinema and a courageous attempt to maintain artistic integrity during a period of increasing political pressure.

What Audiences Thought

The Great Consoler had limited theatrical exposure in the Soviet Union, with many showings restricted to specialized cinemas and cultural institutions. Contemporary audience reactions were mixed, with some viewers appreciating the film's psychological depth and artistic sophistication, while others found it too complex and insufficiently celebratory of Soviet achievements. The film's introspective tone and lack of clear political messaging made it somewhat inaccessible to mass audiences accustomed to more straightforward propaganda films. In the years following its release, the film was largely forgotten by general audiences, though it maintained a reputation among film students and intellectuals who managed to see it through special screenings. The film's limited distribution and subsequent suppression meant that few Soviet citizens had the opportunity to form their own opinions about it. In recent decades, as the film has become more accessible through archival screenings and digital releases, modern audiences have come to appreciate its artistic merits and historical significance, though it remains primarily a film for cinema enthusiasts rather than general viewers.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- German Expressionist cinema

- Soviet montage theory

- O. Henry's short stories

- Dziga Vertov's documentary style

- Eisenstein's intellectual montage

- European psychological cinema of the 1920s

- Literary modernism

- Socialist realist doctrine (in opposition)

This Film Influenced

- Later Soviet films dealing with artistic themes

- Films about journalism ethics

- Psychological dramas about creative professionals

- Cinema exploring individual-state relationships

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The Great Consoler is partially preserved, with some elements of the original film surviving in the Gosfilmofond archive in Russia. The film suffered from the neglect that affected many Soviet films from the early 1930s, particularly those that fell out of political favor. Restoration efforts have been undertaken by film archives, but the complete original version may not exist. Some scenes are believed to be lost or exist only in fragmentary form. The surviving elements have been digitized and preserved as part of efforts to document the history of Soviet cinema. The film's preservation status reflects the broader challenges of maintaining early sound films, which were particularly vulnerable to deterioration. International film archives have cooperated in the preservation effort, recognizing the film's historical and artistic significance. While not completely lost, the film exists in a state that requires ongoing conservation work to ensure its survival for future generations.