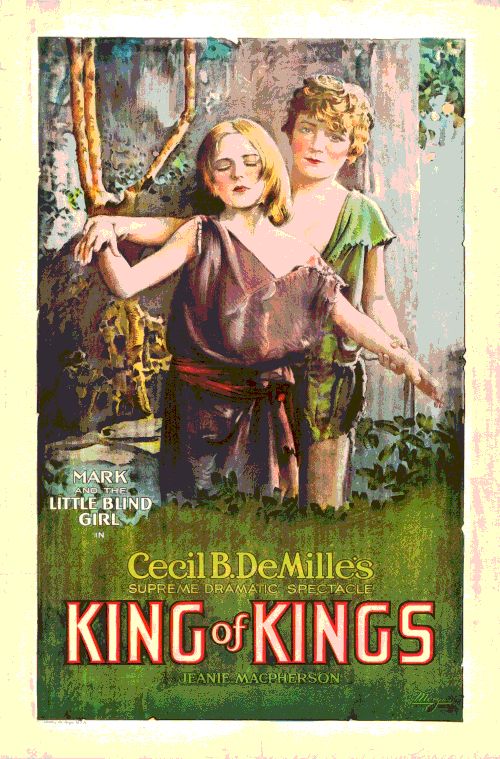

The King of Kings

"The Greatest Story Ever Told"

Plot

Cecil B. DeMille's epic silent film chronicles the life, ministry, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ, beginning with Mary Magdalene's lavish lifestyle and her transformation after encountering Jesus. The film follows Jesus through his miraculous works, including healing the sick and raising Lazarus, his teachings to the multitudes, and the gathering of his disciples. The narrative intensifies with Judas's betrayal, the Last Supper, Jesus's trial before Pontius Pilate and King Herod, and the moving crucifixion sequence. The film culminates in the powerful resurrection scene, where Jesus rises from the tomb, appearing to his followers and ascending to heaven, leaving behind a legacy of faith and redemption that would transform the world.

About the Production

The film required massive sets including a 300-foot long Jerusalem street, employed over 5,000 extras, and featured revolutionary special effects for the resurrection scene. H.B. Warner, who played Jesus, maintained his character both on and off set during production, earning respect from cast and crew. The crucifixion sequence was filmed during an actual eclipse to achieve dramatic lighting effects.

Historical Background

The film was produced during the golden age of silent cinema, just before the transition to sound films would revolutionize the industry. The 1920s saw a surge of interest in religious epics, reflecting America's post-WWI spiritual seeking and the growing influence of religious organizations in American society. Hollywood was also responding to pressure from religious groups who had criticized the industry's moral standards, leading to the Hays Code's implementation. DeMille's film represented a compromise between commercial entertainment and religious respectability. The film's massive budget reflected the confidence studios had in silent films at their peak, while its timing just before the sound revolution made it one of the last great silent epics. The film also emerged during a period of technological innovation in cinema, with advances in cinematography, special effects, and the early use of color processes that DeMille eagerly incorporated.

Why This Film Matters

'The King of Kings' established the template for all future biblical epics, influencing films from 'The Ten Commandments' to 'The Passion of the Christ.' It demonstrated that religious content could be commercially successful without sacrificing reverence or artistic quality. The film's portrayal of Jesus as both divine and human set a standard that subsequent religious films would follow. Its success helped legitimize religious themes in mainstream cinema and paved the way for Hollywood's later biblical productions. The film also represented a significant moment in the relationship between Hollywood and religious institutions, showing that the two could work together to create meaningful entertainment. Its influence extended beyond cinema to religious education, with many churches using clips from the film for teaching purposes. The film's visual imagery, particularly its depiction of Christ, became iconic and influenced religious art and popular culture for decades.

Making Of

The production of 'The King of Kings' was a monumental undertaking that showcased Cecil B. DeMille's legendary attention to detail and showmanship. The director spent months researching biblical texts and consulting with religious authorities to create an authentic yet accessible portrayal of Christ's life. The casting of H.B. Warner as Jesus was controversial at first, as he was primarily known as a character actor, but his intense preparation and dignified performance won over critics and audiences. The film's most challenging sequence was the resurrection, which required innovative special effects including hidden wires, camera tricks, and carefully timed lighting to create the illusion of Christ rising from the tomb. The production employed thousands of extras, many of whom were actual church members recruited from local congregations. DeMille insisted on filming the crucifixion sequence during an actual solar eclipse to achieve the dramatic darkness described in the Bible, though the eclipse only lasted a few minutes, requiring careful planning and multiple takes.

Visual Style

The film's cinematography, by J. Peverell Marley and J. Roy Hunt, was groundbreaking for its time, employing innovative techniques to create both spectacular spectacle and intimate emotional moments. The opening sequence in two-color Technicolor was particularly striking, using the new technology to contrast Mary Magdalene's decadent world with the spiritual realm of Jesus. The cinematographers used dramatic lighting, especially in the crucifixion sequence filmed during an actual eclipse, creating powerful visual metaphors for the spiritual drama. The film employed massive camera movements and sweeping pans to capture the scale of the sets and crowds, while using close-ups effectively to emphasize emotional moments. The resurrection sequence featured revolutionary special effects photography, including multiple exposures and carefully choreographed camera movements to create the illusion of Christ's ascension. The film's visual style influenced countless subsequent biblical epics and established many of the visual conventions for depicting religious subjects on film.

Innovations

The film showcased numerous technical innovations that advanced the art of filmmaking. Its use of two-color Technicolor in the opening sequence was groundbreaking, demonstrating color's potential for dramatic storytelling. The special effects in the resurrection sequence were revolutionary, employing hidden wires, multiple exposures, and carefully synchronized lighting to create a convincing illusion of supernatural events. The film's massive sets, including a 300-foot reconstruction of Jerusalem, represented new achievements in production design and art direction. The cinematography employed innovative camera movements and lighting techniques, including the use of an actual solar eclipse for dramatic effect during the crucifixion sequence. The film's sound synchronization for its 1928 re-release was among the earliest successful attempts to add synchronized sound to a previously silent film. These technical achievements not only served the film's artistic vision but also pushed the boundaries of what was possible in cinema.

Music

The original release featured a specially composed musical score by Hugo Riesenfeld, one of the era's most prominent film composers. The score incorporated traditional hymns, classical pieces, and original compositions to enhance the film's emotional impact. For the 1928 re-release, the film was synchronized with a Movietone soundtrack featuring music and sound effects, making it one of the first films to bridge the silent and sound eras. The musical score was designed to reflect the film's dual nature as both spectacle and spiritual drama, using grand orchestral passages for the crowd scenes and more intimate, reverent music for Jesus's teachings. The soundtrack also featured choral arrangements that emphasized the film's religious themes. The music was so popular that it was published as sheet music and performed in concert halls, demonstrating the film's cultural impact beyond cinema.

Famous Quotes

Jesus: 'I am the resurrection and the life: he that believeth in me, though he were dead, yet shall he live.'

Jesus: 'Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do.'

Jesus: 'It is finished.'

Mary Magdalene: 'Master, I have seen the Lord!'

Pontius Pilate: 'I find no fault in this man.'

Jesus: 'Love one another, as I have loved you.'

Jesus: 'Blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit the earth.'

Judas: 'What will you give me, and I will deliver him unto you?'

Jesus: 'Verily I say unto you, one of you shall betray me.'

Jesus: 'Behold, I make all things new.'

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence in two-color Technicolor showing Mary Magdalene's decadent party, which dramatically contrasts with the introduction of Jesus

- The resurrection scene, where Jesus rises from the tomb with spectacular special effects and ascends to heaven

- The crucifixion sequence filmed during an actual solar eclipse, creating haunting visual imagery

- The Last Supper scene, carefully composed to mirror Leonardo da Vinci's famous painting

- The healing of the blind man sequence, demonstrating Jesus's miraculous powers

- The temptation in the wilderness scene, showing Jesus's spiritual strength

- The triumphal entry into Jerusalem with thousands of extras and elaborate sets

- The scene where Jesus drives the moneychangers from the temple, showing his righteous anger

Did You Know?

- H.B. Warner, who played Jesus, was so dedicated to the role that he refused to be photographed out of costume and maintained a reverent demeanor throughout filming.

- The film's opening sequence was shot in two-color Technicolor, making it one of the earliest films to use color technology for dramatic effect.

- Dorothy Cumming, who played Mary, was a devout Christian in real life and often prayed with cast members between takes.

- The film was banned in some countries for decades due to its religious content and depiction of Christ.

- Cecil B. DeMille consulted with religious leaders and biblical scholars to ensure accuracy, though he took some dramatic liberties.

- The massive Jerusalem set was so elaborate that it was left standing for years and used in other films.

- During filming of the crucifixion scene, temperatures reached over 100 degrees, causing several extras to faint.

- The film's success helped establish the biblical epic as a profitable genre in Hollywood.

- A young Cary Grant can be spotted as one of the Roman soldiers in the crucifixion sequence.

- The film was re-released in 1928 with a synchronized musical score and sound effects using the Movietone system.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film's spectacular production values, sincere performances, and reverent treatment of its subject matter. The New York Times called it 'a magnificent achievement' and 'the most important religious film ever made.' Critics particularly lauded H.B. Warner's performance as Jesus, describing it as 'dignified, powerful, and deeply moving.' The film's technical aspects, especially its cinematography and special effects, were considered groundbreaking. Modern critics continue to appreciate the film's ambition and artistry, with many considering it one of the greatest silent films ever made. Some contemporary reviewers note that while the film reflects the dramatic conventions of its era, its emotional power and visual spectacle remain impressive. The film is often cited as DeMille's masterpiece and a high point of silent cinema.

What Audiences Thought

The film was a tremendous commercial success, attracting both religious and secular audiences. Church groups organized special screenings, and many theaters reported that audiences were moved to tears during the crucifixion and resurrection sequences. The film's popularity was unprecedented for a religious film, proving that sacred subjects could attract mass audiences. Many viewers reported having spiritual experiences while watching the film, and some theaters reported increased church attendance in the weeks following screenings. The film's success led to it being re-released multiple times, including a 1928 version with sound effects and music. Despite its length and serious subject matter, the film appealed to a broad cross-section of American society, from urban sophisticates to rural churchgoers. Its box office success helped establish the biblical epic as a profitable genre and encouraged other studios to invest in similar productions.

Awards & Recognition

- Academy Honorary Award for Cecil B. DeMille (1929) - For distinguished creative achievement in the art of motion pictures

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ (1925)

- The Ten Commandments (1923)

- Intolerance (1916)

- Passion plays and medieval religious dramas

- Classical Hollywood epic tradition

- Biblical illustrations and religious art

- D.W. Griffith's epic filmmaking techniques

This Film Influenced

- The Ten Commandments (1956)

- Ben-Hur (1959)

- The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965)

- Jesus of Nazareth (1977)

- The Passion of the Christ (2004)

- Samson and Delilah (1949)

- Quo Vadis (1951)

- The Robe (1953)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved by the Library of Congress and selected for the National Film Registry in 1999 for its cultural, historical, and aesthetic significance. Multiple restoration efforts have been undertaken, with the most complete version available on Blu-ray from Kino Lorber featuring both the original 1927 version and the 1928 sound re-release. The Technicolor opening sequence survives in excellent condition, though some scenes exist only in lower-quality copies. The George Eastman Museum holds original nitrate elements of the film, ensuring its preservation for future generations.