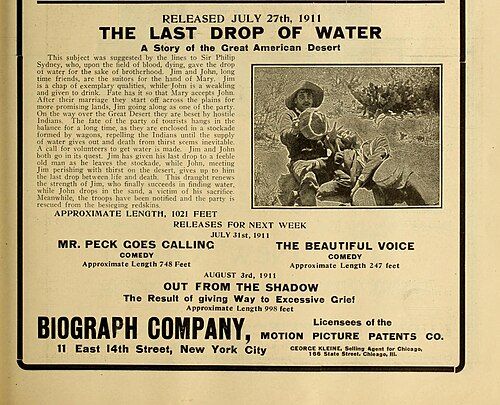

The Last Drop of Water

Plot

In this early Western short film, a wagon train traveling westward across the harsh desert finds themselves in a desperate situation when their water supply runs completely dry. As the group struggles with dehydration and despair, they face an additional threat when they are attacked by hostile Indians who surround their vulnerable position. With the wagon train's survival hanging in the balance, one brave man volunteers to undertake a perilous journey through the dangerous desert terrain in search of a water source that could save everyone. The film builds tension as the hero races against time and the elements, knowing that the lives of his fellow travelers depend entirely on his success in finding the last drop of water they need to survive.

About the Production

This film was one of hundreds of short films D.W. Griffith directed for the Biograph Company between 1908 and 1913. The production utilized the California landscape to simulate the American West, a common practice for early Westerns. The film was shot on 35mm film with the standard Biograph aspect ratio of the era. As with most Biograph productions of this period, the film was made quickly and efficiently, typically completed in just a few days of shooting.

Historical Background

The Last Drop of Water was released in 1911, during a pivotal transitional period in American cinema. The film industry was still largely based on the East Coast, but California was rapidly emerging as the new center of film production due to its favorable weather and diverse locations. This was the era before feature-length films became standard, when movie theaters typically presented programs of multiple short films. D.W. Griffith was at the height of his Biograph period, directing hundreds of short films that would help establish the language of cinema. The Western genre was already popular with audiences, reflecting America's ongoing fascination with frontier mythology and westward expansion. The film also predates the Motion Picture Patents Company's decline and the subsequent rise of independent filmmakers. In broader historical context, 1911 was just three years before the outbreak of World War I, during a period of relative peace and rapid technological advancement in the United States, including the burgeoning film industry.

Why This Film Matters

As an early example of the Western genre, The Last Drop of Water helped establish many of the tropes and narrative conventions that would define Western cinema for decades. The film's emphasis on survival against harsh natural elements and hostile threats reflected broader American cultural myths about the frontier experience and manifest destiny. D.W. Griffith's work during this Biograph period was instrumental in developing cinematic language, and even this relatively simple short film contributed to the evolution of film grammar. The film also represents an early example of cinema's ability to create suspense and emotional engagement through visual storytelling rather than relying on dialogue. Its preservation and study today provides valuable insight into the early development of American narrative cinema and the Western genre specifically. The film's themes of perseverance and sacrifice in the face of overwhelming odds resonated with early 20th century audiences and continue to influence how the American West is portrayed in media.

Making Of

The Last Drop of Water was produced during D.W. Griffith's formative years at the Biograph Company, where he developed many of the cinematic techniques that would later define his career. Griffith was known for his meticulous attention to detail even in these early short films, often pushing his actors to deliver more naturalistic performances than was typical for the period. The desert scenes were likely filmed on location in California, taking advantage of the state's diverse landscapes to stand in for the American West. Blanche Sweet, who was emerging as one of Griffith's favorite leading ladies, would later recall the demanding physical conditions of shooting these early Westerns. The film's production followed Griffith's typical efficient methods at Biograph, with minimal scripting and emphasis on visual storytelling over intertitles. This approach allowed Griffith to direct an enormous number of films while experimenting with techniques like cross-cutting, camera movement, and narrative structure that would revolutionize cinema.

Visual Style

The cinematography in The Last Drop of Water was typical of Biograph productions from 1911, utilizing the natural California landscape to stand in for the American West. The film was shot on 35mm black and white film using stationary cameras, as camera movement was still limited in this early period of cinema. The cinematographer, likely Billy Bitzer or another Biograph regular, would have focused on creating clear compositions that effectively told the story visually. The desert scenes would have emphasized the harshness of the environment through wide shots showing the vast, empty landscape surrounding the vulnerable wagon train. The film probably employed the emerging technique of cross-cutting between different actions to build suspense, a method Griffith was pioneering during this period. The visual style would have been straightforward and functional, prioritizing narrative clarity over artistic experimentation, though Griffith was already beginning to push the boundaries of what was possible in cinematic storytelling.

Innovations

While The Last Drop of Water may not represent major technical innovations, it was part of D.W. Griffith's ongoing development of cinematic language during his Biograph period. The film likely employed cross-cutting techniques to build tension between multiple simultaneous actions, a method Griffith was pioneering in these years. The use of location shooting in California to simulate the American West was becoming more common but still represented a technical challenge in 1911. The film's production utilized the standard 35mm film format of the era, with the typical projection speed of 16-18 frames per second. The desert scenes required careful planning to capture the harsh environmental conditions effectively. While not groundbreaking, the film represents the steady refinement of narrative filmmaking techniques that would soon revolutionize cinema with Griffith's later feature films.

Music

As a silent film from 1911, The Last Drop of Water had no synchronized soundtrack. Musical accompaniment would have been provided live during theatrical screenings, typically by a pianist or small orchestra using stock music appropriate to the on-screen action. The score would have included dramatic music for the Indian attack scenes, tense music during the search for water, and triumphant music during the resolution. The specific musical selections would have varied by theater and musician, as there was no standardized score for the film. Some larger theaters might have used cue sheets provided by the Biograph Company suggesting appropriate musical pieces for different scenes. The musical accompaniment was essential to the silent film experience, providing emotional context and helping to maintain audience engagement throughout the narrative.

Famous Quotes

As a silent film, The Last Drop of Water contains no spoken dialogue. Any quotes would come from intertitles, which are not widely documented for this specific film.

Memorable Scenes

- The desperate scene where the wagon train realizes they have completely run out of water, showing the panic and despair of the pioneers facing death in the harsh desert; The tense sequence where Indians attack the vulnerable wagon train, creating a dual threat of both human enemies and natural dehydration; The hero's perilous journey across the desert landscape in search of water, emphasizing the vast emptiness and danger of the environment; The climactic moment when water is finally found, representing salvation and survival for the entire wagon train.

Did You Know?

- This was one of the earliest Western films directed by D.W. Griffith, who would later direct the controversial but technically groundbreaking 'The Birth of a Nation' (1915)

- Blanche Sweet, who stars in the film, was just 17 years old when this was made and would become one of Griffith's favorite actresses

- The film was shot in California, which would soon become the center of the American film industry with Hollywood's rise

- Like many films of this era, it was released as part of a program with multiple short films rather than as a standalone feature

- The Biograph Company, which produced the film, was one of the most important early American film studios before being absorbed into larger conglomerates

- This film was made during Griffith's most prolific period, when he directed dozens of films per year for Biograph

- The film's theme of survival in the harsh American West would become a staple of the Western genre for decades to come

- Charles West, who appears in the film, was a regular in Griffith's Biograph productions, appearing in over 100 of the director's films

- The film was released before the standardization of feature-length films, when most movies were 10-20 minutes long

- Joseph Graybill, another cast member, died tragically young in 1913 at age 27, making this one of his surviving film appearances

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception for The Last Drop of Water is difficult to trace due to the limited film criticism infrastructure of 1911. Most newspapers of the era focused more on general movie theater listings rather than detailed film reviews. The film was likely received as a solid example of the popular Western genre that audiences expected. Modern film historians and critics recognize the film as an important artifact from Griffith's Biograph period, though it's generally considered less significant than his more ambitious works from the same era. The film is valued today primarily for its historical importance rather than its artistic merits, though it demonstrates Griffith's growing mastery of cinematic techniques even in this relatively simple production. Film scholars have noted that even in these early Western shorts, Griffith was experimenting with cross-cutting to build tension and create emotional impact.

What Audiences Thought

Audience reception in 1911 would have been positive for The Last Drop of Water, as Westerns were among the most popular genres of early American cinema. The film's themes of survival, heroism, and conflict with Native Americans (though portrayed through the stereotypical lens of the period) would have resonated with contemporary audiences. The 17-minute runtime was standard for the era, and the film would have been shown as part of a varied program of shorts rather than as a standalone attraction. Modern audiences viewing the film today, primarily through film archives and special screenings, tend to appreciate it more for its historical value than for entertainment. The film provides a window into early 20th century American cultural attitudes and cinematic techniques, making it valuable for film enthusiasts and scholars interested in the evolution of the Western genre and American cinema generally.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Early Western literature

- Stagecoach melodramas

- Frontier stories

- Previous Biograph Westerns

This Film Influenced

- Later D.W. Griffith Westerns

- Classic Hollywood Westerns

- Desert survival films

- Wagon train Westerns

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The Last Drop of Water is believed to survive in film archives, though it may not be widely accessible to the public. As a Biograph production from 1911, it would have been printed on 35mm nitrate film, which deteriorates over time. The film is likely preserved through paper prints submitted to the Library of Congress for copyright purposes, a common practice for Biograph films of this era. These paper prints have been used to restore many early films. The Museum of Modern Art and other film archives may hold copies of the film. However, like many films from this period, it may not be available on home media or streaming platforms, limiting access primarily to researchers and specialized screenings.