The Life and Death of King Richard III

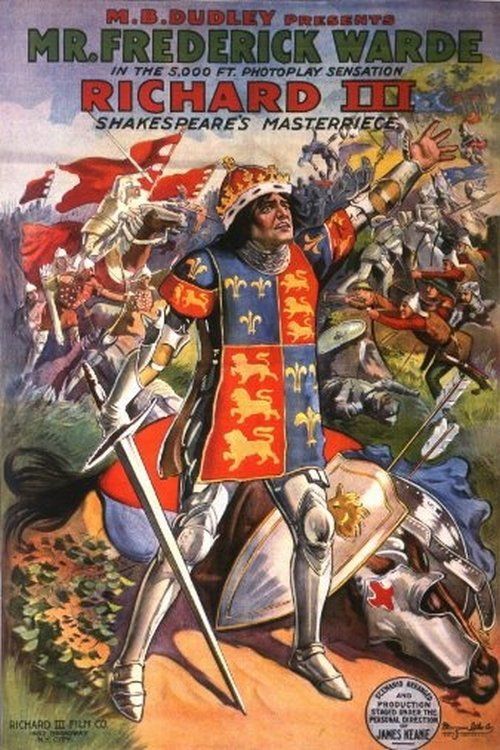

"The Sensation of the Century!"

Plot

The film follows the ruthless ascent of Richard, Duke of Gloucester, a manipulative and physically deformed nobleman who orchestrates a series of murders to seize the English throne. Beginning with the assassination of King Henry VI and the subsequent death of King Edward IV, Richard systematically eliminates his rivals, including his own brother Clarence and his young nephews, the Princes in the Tower. He successfully woos Lady Anne, the widow of a man he killed, and uses political chicanery to convince the public to demand his coronation. His tyrannical reign is ultimately challenged by the Earl of Richmond, leading to the climactic Battle of Bosworth Field where Richard is defeated and killed. The narrative concludes with the rise of the Tudor dynasty, promising a new era of peace for England.

About the Production

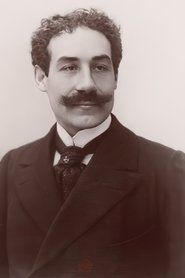

The film was a massive undertaking for 1912, featuring what were then considered 'epic' production values. Marketing materials claimed the production utilized 1,000 people, 200 horses, and five distinct battle scenes. It was an international co-production between French company Film d'Art and American interests. Notably, the film was designed as a 'prestige' vehicle for stage star Frederick Warde, who used the film to tour the country without the expense of a full theatrical troupe. The production famously included a three-masted warship on real water to enhance the historical scale.

Historical Background

In 1912, the American film industry was in a state of transition from 'nickelodeon' shorts to feature-length 'prestige' pictures. This was the first year that feature-length films were produced in the United States, and 'Richard III' was at the forefront of this movement. Culturally, there was a significant push to 'legitimize' cinema as a high art form capable of handling literary giants like Shakespeare. This film was released just a few years before D.W. Griffith's 'The Birth of a Nation' (1915), which would further revolutionize the feature format.

Why This Film Matters

The film's significance lies in its status as a 'missing link' in cinema history. For decades, historians believed early American features were largely lost, but the discovery of 'Richard III' proved that sophisticated narrative techniques—such as cross-cutting, camera pans, and deep-space composition—were already being utilized as early as 1912. It served as a bridge between the 19th-century theatrical tradition and the 20th-century cinematic language.

Making Of

The production was a landmark in early narrative ambition, moving away from short 'vignettes' toward complex, multi-act storytelling. Director James Keane, making his feature debut, had to choreograph massive crowds and horses in open-air locations in New York, a stark contrast to the cramped studio sets of the era. Frederick Warde, a 61-year-old veteran of the stage, embraced the new medium despite the skepticism of his peers, seeing it as a way to preserve his legacy. The 'battle' scenes were filmed with a level of scale rarely seen before 1912, utilizing the natural landscapes of Westchester to simulate the English countryside. The film also features a unique framing device where Warde appears in modern dress at the beginning and end to bow before a theatrical curtain, emphasizing the film's roots in high theater.

Visual Style

The cinematography is characterized by wide, static 'proscenium' shots that capture the full bodies of the actors, though it features notable innovations for the time. These include early camera pans to follow action and the use of deep focus to show characters approaching from the far distance. The film also utilized tinting and toning—using blue for night scenes and amber for interiors—to convey mood and setting to the audience.

Innovations

The film is a technical marvel for 1912 due to its 55-minute length (five reels), which was unprecedented for an American production at the time. It successfully integrated large-scale outdoor battle sequences with interior palace scenes. The use of hand-stenciled color in certain sequences and the complex (for the time) editing within scenes to show movement between rooms marked a significant step forward in film grammar.

Music

As a silent film, it originally had no synchronized soundtrack, but was intended to be accompanied by live music and Warde's live narration. For the 1996 restoration premiere, Robert Israel composed a chamber orchestra score. In 2001, the film received a high-profile score by Ennio Morricone for its DVD release, which added a modern, atmospheric layer to the vintage visuals.

Famous Quotes

My kingdom for a horse! (Presented via intertitle during the final battle)

A horse! A horse! My kingdom for a horse! (Recited live by Frederick Warde during screenings)

I am determined to prove a villain. (Context: Richard's opening soliloquy, often recited by Warde before the film started)

Memorable Scenes

- The opening scene where Frederick Warde, in modern 1912 attire, steps from behind a velvet curtain to bow to the camera, bridging the gap between theater and film.

- The murder of the Princes in the Tower, which is depicted with a chilling, shadowy atmosphere that was quite advanced for the period.

- The Battle of Bosworth Field, featuring hundreds of extras and horses, showcasing a scale of production that was revolutionary for 1912.

- The scene where Richard woos Lady Anne over the coffin of her father-in-law, captured in a long, unbroken take that emphasizes the actors' physical performances.

Did You Know?

- It is the oldest surviving American feature-length film known to exist in its entirety.

- The film was considered lost for over 70 years until a print was discovered in 1996 in the private collection of William Buffum.

- Frederick Warde, the star, would often appear in person at screenings to give lectures and recite Shakespearean monologues during reel changes.

- The film uses the 'Film d'Art' style, which aimed to bring high-brow theatrical prestige to the 'lowly' medium of motion pictures.

- The intertitles use the phonetic spelling 'Duke of Gloster' instead of 'Gloucester' to make it more accessible to general audiences.

- It is believed to be the first feature-length adaptation of a William Shakespeare play ever made.

- The film includes scenes from 'Henry VI, Part 3' to provide backstory for Richard's villainy, a technique borrowed from Colley Cibber's 1699 stage adaptation.

- The 1996 restoration by the AFI was likened by CEO Jean Picker Firstenberg to finding a 'lost Rembrandt.'

- The film features an early color process of tinting and toning, with specific hand-stenciled sequences.

- A new score for the 2001 DVD release was composed by the legendary Ennio Morricone.

What Critics Said

In 1912, the film was hailed as a 'Sensation of the Century' and a triumph of 'historically correct' detail. Modern critics, upon its 1996 rediscovery, noted that while the acting is rooted in the broad, pantomime style of the era, the film is surprisingly engaging and technically advanced. Kevin Thomas of the Los Angeles Times described it as a 'surprisingly engaging example of the well-filmed play,' praising its choreography and scale.

What Audiences Thought

Original audiences were reportedly enthralled by the spectacle and the opportunity to see a famous stage star like Frederick Warde for a fraction of the price of a theater ticket. The film was a success on the 'states rights' distribution circuit, where it toured extensively. Modern audiences generally view it as a fascinating historical artifact, though the lack of close-ups and the theatrical acting style can be a barrier for those unaccustomed to early silent cinema.

Awards & Recognition

- Special Plaque from the AFI Board of Trustees (awarded to William Buffum in 1996 for preservation)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- William Shakespeare's play 'Richard III'

- Colley Cibber's 1699 stage adaptation

- The 'Film d'Art' movement in France

This Film Influenced

- Richard III (1955)

- Richard III (1995)

- The Hollow Crown (2012)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Fully restored. After being lost for decades, a near-pristine nitrate print was found in 1996. It was restored by the American Film Institute and is now preserved at the Library of Congress.