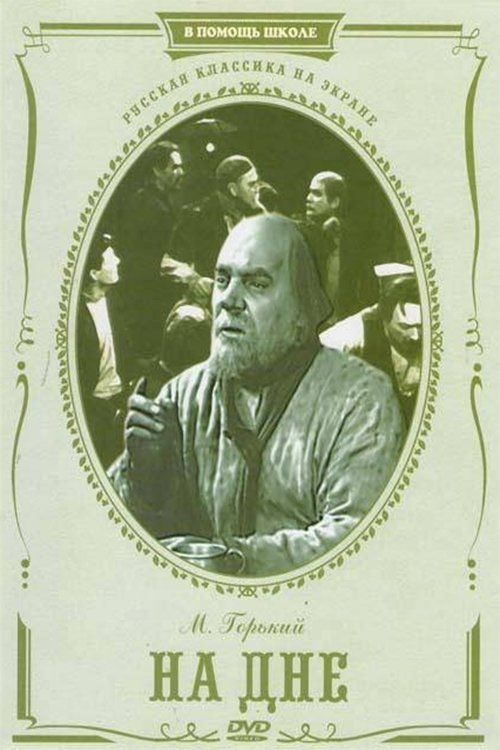

The Lower Depths

Plot

Set in a dilapidated flophouse near the Volga River, this Soviet adaptation of Maxim Gorky's classic play follows the lives of impoverished Russians who have fallen to the lowest rungs of society. The residents, including a dying alcoholic actor, a thief, a fallen nobleman, and various other outcasts, struggle to maintain their dignity while grappling with poverty, despair, and false hope. The arrival of a mysterious traveler who claims to believe in human goodness briefly inspires the inhabitants, but his philosophy is challenged by the harsh realities of their existence. As tensions rise and secrets are revealed, the film explores whether truth or comforting lies are more valuable for those living in such desperate circumstances. The narrative culminates in tragedy when one character commits suicide after losing faith in both humanity and the possibility of a better life.

About the Production

Filmed during the final years of Stalin's rule, the production had to navigate strict censorship requirements while adapting Gorky's controversial work. The filmmakers had to ensure the portrayal aligned with Soviet ideological principles, emphasizing social critique while avoiding excessive pessimism. Director Andrey Frolov took particular care in casting, selecting actors from the Moscow Art Theatre who were familiar with Gorky's work. The set design meticulously recreated the squalid conditions of a 19th-century Russian flophouse, with attention to period-accurate details.

Historical Background

The film was produced during the height of Stalin's regime in the Soviet Union, a period characterized by strict artistic censorship and socialist realism as the mandated artistic style. 1952 was a particularly tense year in Soviet history, coming just before Stalin's death and during the early stages of the Cold War. The decision to adapt Gorky's work was significant, as Gorky was officially celebrated as a founder of socialist realism despite his works often containing complex, ambiguous elements. The film's production occurred during the 'Zhdanov Doctrine' era, which demanded that all art serve political purposes. This context makes the film's exploration of poverty and despair particularly noteworthy, as it had to navigate between faithful adaptation and ideological compliance. The film's release just months before Stalin's death means it represents one of the final artistic statements of the Stalinist era.

Why This Film Matters

This adaptation holds an important place in Soviet cinema as one of the definitive film versions of Gorky's most famous play. It represents a bridge between the theatrical traditions of the Moscow Art Theatre and the cinematic language of Soviet film. The film contributed to the ongoing Soviet discourse about social justice and the role of art in society. Unlike many Western adaptations that emphasized individual tragedy, this version highlighted the collective nature of the characters' suffering and their potential for solidarity. The film also served as a cultural export, being shown in Eastern Bloc countries as an example of Soviet artistic achievement. Its preservation of Gorky's text helped maintain the playwright's cultural relevance for new generations of Soviet citizens. The film remains significant today as a document of how Soviet cinema handled complex literary works during a period of intense political pressure.

Making Of

The production faced significant challenges in adapting Gorky's notoriously difficult play for the screen. Director Frolov worked closely with screenwriters to condense the play's episodic structure while maintaining its philosophical depth. The casting process was rigorous, with Frolov insisting on actors who could convey both the physical and spiritual poverty of their characters. Many of the performers had experience with the play on stage, bringing theatrical intensity to their film performances. The cinematography employed chiaroscuro lighting to emphasize the claustrophobic atmosphere of the flophouse, a technique that was somewhat unusual for Soviet cinema of the period. The sound design was particularly innovative, using ambient noises from the Volga River and the creaking of the old building to create an immersive environment.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Ivan Turchaninov employed dramatic chiaroscuro lighting to create the claustrophobic atmosphere of the flophouse, using shadows to emphasize the psychological states of the characters. The camera work was relatively static for the period, focusing on composition and the interplay of light and dark rather than movement. Deep focus techniques were used to keep multiple characters in sharp relief within the cramped quarters, emphasizing their interconnected fates. The visual style drew inspiration from German Expressionism while remaining within the bounds of socialist realism. Particular attention was paid to the texture of decay, with close-ups highlighting the peeling paint, rotting wood, and worn objects that surrounded the characters. The color palette, though limited by the technology of the time, used muted tones to reinforce the sense of despair and poverty.

Innovations

The film featured innovative set design that created a fully realized flophouse environment, allowing for complex camera movements within the confined space. The production used advanced sound recording techniques for the period, capturing both dialogue and ambient environmental sounds with clarity. The makeup and costume departments achieved remarkable authenticity in depicting the physical toll of poverty on the characters. The film's editing successfully maintained the play's dramatic tension while adapting its theatrical structure for cinematic pacing. Special attention was paid to historical accuracy in props and set dressing, with the production team consulting historical experts to ensure 19th-century authenticity. The film also demonstrated sophisticated use of lighting equipment to create mood and atmosphere within the challenging indoor locations.

Music

The musical score was composed by Vano Muradeli, who created a somber, atmospheric soundtrack that underscored the tragic elements of the story without overwhelming the dialogue. Muradeli incorporated elements of Russian folk music, particularly in scenes that referenced the characters' past lives or hopes for redemption. The score made subtle use of leitmotifs for different characters, with the Baron's theme containing echoes of forgotten nobility while the thief's music had more restless, urban rhythms. The sound design was particularly effective in creating the ambient atmosphere of the flophouse, with the constant background noise of the Volga River, creaking floorboards, and distant city sounds. The film's use of silence was also notable, with several key scenes featuring minimal music to emphasize the weight of the characters' words and thoughts.

Famous Quotes

Man - that sounds proud! Yes! Man! It has a ring to it... Man! It's magnificent! It's all there is!

The truth is the god of the free man!

All people are superfluous on this earth.

Even a beast can feel! But a man - he must think!

I don't need a God, but I need a belief!

Memorable Scenes

- The Baron's monologue about his lost dignity and aristocratic past, delivered while polishing his worn boots

- The climactic confrontation between the traveler and the other residents about the nature of truth and illusion

- The final scene where the characters react to the suicide, their faces revealing different forms of despair and resignation

- The opening sequence establishing the flophouse atmosphere with its dim lighting and crowded conditions

- The scene where the dying actor delivers his final performance, mixing theatrical grandeur with genuine pathos

Did You Know?

- This was the third Soviet adaptation of Gorky's play, following versions in 1912 and 1936

- Director Andrey Frolov was a student of Vsevolod Pudovkin, one of the pioneers of Soviet montage theory

- The film was released just one year before Stalin's death, making it one of the last major literary adaptations of his era

- Sergei Blinnikov, who played the Baron, was a People's Artist of the USSR and had previously appeared in Eisenstein's 'Alexander Nevsky'

- The production faced initial resistance from Soviet censors who were concerned about the play's pessimistic elements

- Unlike Kurosawa's 1957 adaptation, this version remained faithful to the original Russian setting and period

- The film was rarely shown outside the Soviet Union during the Cold War due to its perceived ideological content

- Maxim Gorky had personally approved the first Soviet film adaptation in 1912, though he died long before this version

- The flophouse set was so realistically constructed that some actors reported feeling genuinely depressed during filming

- This adaptation was used in Soviet film schools as an example of literary adaptation techniques

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics praised the film for its faithful adaptation of Gorky's work and its powerful performances, particularly Sergei Blinnikov's portrayal of the Baron. Pravda newspaper commended director Frolov for successfully translating the play's philosophical depth to the screen while maintaining ideological clarity. Western critics who saw the film at international festivals noted its technical competence but sometimes criticized it for being too literal in its adaptation. Modern film historians have reassessed the work, recognizing it as a sophisticated example of Soviet literary adaptation that managed to preserve the ambiguity of Gorky's original while working within strict ideological constraints. The film is now appreciated for its atmospheric cinematography and the ensemble cast's nuanced performances, which avoided the caricature sometimes found in Soviet films about the pre-revolutionary era.

What Audiences Thought

The film was well-received by Soviet audiences, who were familiar with Gorky's work from school curricula and theatrical productions. Many viewers praised the authenticity of the performances and the film's unflinching look at poverty, which resonated with those who remembered or had heard about pre-revolutionary conditions. The film ran successfully in Soviet cinemas for several months, particularly in major cities like Moscow and Leningrad. In later years, it became a staple of Soviet television programming during literary festivals and Gorky commemorations. Among Eastern Bloc audiences, the film was appreciated for its artistic merit and its confirmation of Soviet cultural superiority in adapting classic literature. Modern Russian audiences who have discovered the film through retrospectives and film archives often comment on its timeless relevance and the power of its social commentary.

Awards & Recognition

- Stalin Prize (State Prize of the USSR) for Sergei Blinnikov (1952)

- Vasilyev Brothers State Prize of the RSFSR for Andrey Frolov (1952)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Maxim Gorky's original 1902 play

- Konstantin Stanislavski's Moscow Art Theatre productions

- Soviet montage theory

- German Expressionist cinema

- Socialist realist aesthetic principles

- 19th-century Russian literary tradition

This Film Influenced

- The Lower Depths (1957) - Akira Kurosawa's adaptation

- Soviet films of the 1950s dealing with social themes

- Later Russian adaptations of Gorky's works

- Films about poverty and social marginalization in Soviet cinema

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved in the Gosfilmofond of Russia, the state film archive, where it has been maintained in good condition. A digital restoration was completed in 2010 as part of a broader project to preserve classic Soviet cinema. The restored version has been shown at various film retrospectives and is available in high quality for archival purposes. Original film elements, including the camera negative, are stored under controlled conditions to prevent further deterioration. The film has also been preserved through international film archives, including copies at the Library of Congress and the British Film Institute, ensuring its survival for future generations.