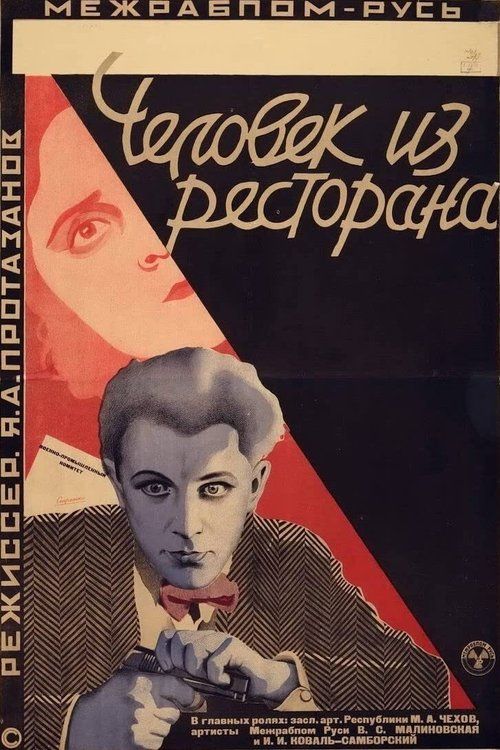

The Man from the Restaurant

Plot

The film follows Skvortsov, a dedicated and proud waiter working in an elegant Moscow restaurant during the final years of the Russian Empire. He takes immense satisfaction in serving the wealthy aristocratic clientele with impeccable precision and dignity, despite his humble social position. However, his personal life is marked by profound tragedy - his son was killed fighting in the Russian Civil War, and his wife subsequently died of grief, leaving him alone to navigate the turbulent times. When the October Revolution occurs and the restaurant is transformed into a workers' canteen, Skvortsov must adapt to serving a completely different clientele and operating under the new Soviet system. The film powerfully contrasts the opulent, decadent world of pre-revolutionary Russia with the emerging socialist society, using the waiter's experiences to explore themes of class consciousness, human dignity, and the personal costs of social transformation.

About the Production

The film was based on a story by Ivan Shmelyov and was one of the few Soviet films of the 1920s that depicted pre-revolutionary Russia with relative nuance rather than pure condemnation. Director Yakov Protazanov, who had worked extensively before the revolution and temporarily emigrated, brought a unique perspective to the material. The production faced ideological challenges as it portrayed a servant character with dignity rather than as a mere victim of the old regime. The restaurant scenes were meticulously recreated to show the stark contrast between pre- and post-revolutionary dining experiences.

Historical Background

The film was produced during the New Economic Policy (NEP) period in the Soviet Union, a time of relative cultural liberalization that allowed for more artistic experimentation. This was the golden age of Soviet silent cinema, with directors like Eisenstein, Pudovkin, and Vertov creating groundbreaking works. However, 'The Man from the Restaurant' stood apart from the more explicitly propagandistic works of its contemporaries by focusing on individual human experience rather than collective revolutionary struggle. The film's production coincided with the tenth anniversary of the October Revolution, a time when Soviet cinema was increasingly being used to legitimize the new regime. The film's nuanced approach to depicting pre-revolutionary Russia reflected the complex relationship many Soviet artists had with the country's past. By 1927, the Soviet film industry had recovered from the chaos of the revolution and civil war, establishing state studios like Goskino that could produce sophisticated productions with international appeal.

Why This Film Matters

'The Man from the Restaurant' represents a crucial moment in Soviet cinema's development, demonstrating that films could explore complex human experiences while still serving ideological purposes. The film's sympathetic portrayal of a working-class character who maintained his dignity under both regimes helped establish a template for Soviet cinema's approach to the 'positive hero.' Its international success proved that Soviet films could compete artistically with Western productions without abandoning their cultural identity. The film's exploration of class dynamics through the microcosm of a restaurant influenced countless later Soviet and international films. Michael Chekhov's performance set new standards for acting in silent cinema, particularly in his ability to convey complex emotions through subtle gestures rather than broad melodrama. The film also contributed to the cultural memory of pre-revolutionary Russia, providing one of the most detailed cinematic records of the country's social hierarchy before the revolution.

Making Of

The making of 'The Man from the Restaurant' was particularly significant because director Yakov Protazanov had returned to the Soviet Union in 1923 after several years working in Europe. This gave him a unique perspective on both pre- and post-revolutionary Russia. The casting of Michael Chekhov was considered a coup, as he was already a celebrated stage actor from the Moscow Art Theatre. Chekhov brought method acting techniques to his performance, which was unusual for silent cinema of the era. The production team spent months researching authentic restaurant settings and service protocols of the pre-revolutionary era to ensure historical accuracy. The film's most challenging sequence was the revolutionary transformation scene, where the luxury restaurant is converted into a workers' canteen - this required extensive set changes that had to be filmed in continuity. The production faced scrutiny from Soviet cultural authorities who were concerned about the film's nuanced portrayal of the old regime, but Protazanov successfully argued that the film ultimately supported Soviet values by showing the superiority of the new social order.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Vladimir Siversen was notable for its sophisticated use of lighting to contrast the opulent pre-revolutionary restaurant with the stark simplicity of the workers' canteen. The film employed innovative camera techniques including tracking shots that followed the waiter through the restaurant, creating a sense of continuous space and movement. Siversen used soft focus techniques to create dreamlike sequences representing the waiter's memories of his family. The film's visual style was influenced by German expressionism in its use of shadows and angles, but maintained a distinctly Russian realist approach in its depiction of social environments. The transformation sequence from luxury restaurant to workers' canteen was particularly praised for its visual storytelling without intertitles. The cinematography also made effective use of close-ups to capture the subtle emotions of Michael Chekhov's performance, a technique that was still relatively new in Soviet cinema.

Innovations

The film was notable for its sophisticated use of editing to create temporal transitions between pre- and post-revolutionary periods. The restaurant transformation sequence was achieved through innovative set design that allowed for continuous filming during the radical change in environment. The film employed early forms of montage theory, though less radically than Eisenstein's works of the same period. The production pioneered techniques for filming in confined spaces, using specially designed camera mounts to navigate the restaurant set. The film's makeup effects, particularly the aging of the main character, were considered advanced for their time. The lighting design was particularly innovative, using different color gels (tinting) to distinguish between time periods and emotional states. The film also featured some of the earliest uses of camera movement to follow a character through complex spaces, influencing later Soviet and international cinema.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Man from the Restaurant' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The typical score would have combined classical pieces for the restaurant scenes with more revolutionary songs for the post-revolution sequences. The film's original cue sheets, if they existed, have not survived, but contemporary orchestral reconstructions have been created for modern screenings. These reconstructions typically feature works by Russian composers like Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninoff for the pre-revolutionary scenes, transitioning to Soviet composers like Prokofiev and Shostakovich for the revolutionary sequences. The contrast between the musical styles helps emphasize the film's themes of social transformation. Modern restorations have featured newly composed scores by contemporary musicians who specialize in silent film accompaniment.

Did You Know?

- Michael Chekhov, who played the lead role of Skvortsov, was Anton Chekhov's nephew and a renowned acting teacher who later influenced Hollywood stars like Marilyn Monroe and Clint Eastwood

- Director Yakov Protazanov was one of the few prominent pre-revolutionary Russian directors who successfully continued working under the Soviet regime

- The film was based on a short story by Ivan Shmelyov, a writer who had emigrated after the revolution and was critical of the Soviet regime

- This was one of the rare Soviet films of the 1920s that portrayed pre-revolutionary life with some degree of complexity rather than simple caricature

- The restaurant set was so detailed and realistic that it became one of the most expensive sets built in Soviet cinema up to that point

- The film's international success helped establish Soviet cinema's reputation beyond propaganda pieces

- Vera Malinovskaya, who played one of the aristocratic customers, was one of the most popular actresses of early Soviet cinema

- The film was temporarily banned in some regions for its supposedly sympathetic portrayal of the old regime's servants

- The transformation scenes from luxury restaurant to workers' canteen were achieved without special effects, relying entirely on set dressing and props

- The film's title became a cultural reference in Soviet Russia for someone who had served the old regime but adapted to new times

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics praised the film for its artistic merit while questioning whether it sufficiently condemned the old regime. Pravda's review noted the film's technical excellence but warned against 'excessive nostalgia' for pre-revolutionary times. Western critics were generally enthusiastic, with Variety praising its 'universal human appeal' and technical sophistication. Modern film historians consider the film a masterpiece of silent cinema, particularly admiring its nuanced social commentary and Chekhov's performance. The film is now recognized as an important example of how Soviet cinema could balance artistic expression with ideological requirements during the NEP period. Recent retrospectives have highlighted the film's relevance to contemporary discussions about service work, class mobility, and social change. The restoration of the film in the 1990s led to renewed critical appreciation, with many scholars noting its influence on later films about social transformation.

What Audiences Thought

The film was highly popular with Soviet audiences upon its release, particularly appealing to older viewers who remembered pre-revolutionary Russia. Many viewers appreciated the film's realistic portrayal of restaurant life and its complex protagonist. The film's success at the domestic box office was significant for a Soviet production of its time. International audiences also responded positively, with the film achieving commercial success in several European countries. However, some younger Soviet viewers criticized the film for not being revolutionary enough in its approach. The film's popularity endured through the 1930s despite changing cultural policies, suggesting its themes resonated beyond its immediate historical context. Modern audiences at film festivals and retrospectives continue to respond strongly to the film's humanistic approach and technical artistry.

Awards & Recognition

- No major awards were given to Soviet films in 1927 as the international film festival circuit was not yet established

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Works by Ivan Shmelyov

- German Expressionist cinema

- Soviet montage theory

- Pre-revolutionary Russian literature

- European realist cinema of the 1920s

This Film Influenced

- later Soviet films about the revolution

- international films about service workers

- movies exploring class dynamics through workplace settings

- films contrasting pre- and post-revolutionary societies