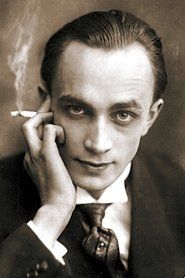

The Man Who Laughs

"The Man Whose Face Was His Curse!"

Plot

In 1690 England, Lord Clancharlie refuses to bow to the despotic King James II and is brutally executed. His young son Gwynplaine is abandoned by the king's order and falls into the hands of Dr. Hardquanonne, a comprachico who surgically carves a permanent grin onto the boy's face. Years later, Gwynplaine travels with a carnival sideshow where he performs as 'The Man Who Laughs' alongside the blind girl Dea, whom he loves deeply. When the carnival is shut down, Gwynplaine discovers he is the rightful heir to a peerage and is summoned to the House of Lords, where he must choose between aristocratic privilege and his true love. Ultimately, rejected by both the aristocracy who mock his appearance and the common folk who fear him, Gwynplaine returns to Dea, and they sail away together, finding acceptance in their love for each other.

About the Production

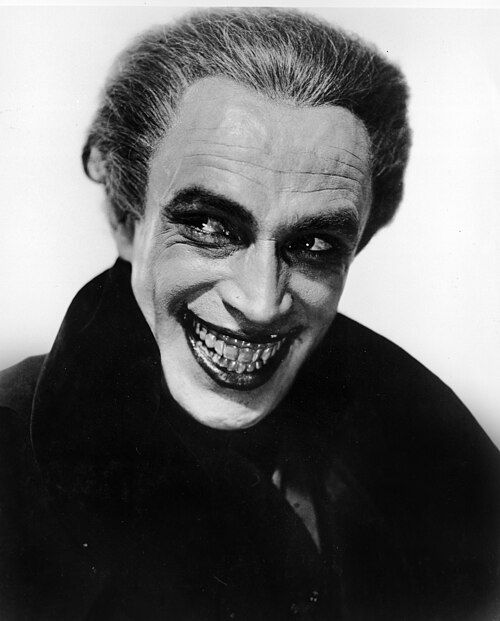

Conrad Veidt's makeup for the permanent grin was achieved using prosthetics and wire, causing him considerable discomfort during filming. The production invested heavily in elaborate sets to recreate 17th-century England, including detailed reproductions of the House of Lords. Director Paul Leni brought his German Expressionist background to the film's visual style, creating dramatic shadows and atmospheric lighting that enhanced the horror elements. The carnival sequences featured actual circus performers and were filmed on specially constructed sets.

Historical Background

Released in 1928, 'The Man Who Laughs' emerged during the transition period between silent and sound films, representing one of the last major silent productions before the talkies revolutionized cinema. The late 1920s saw the rise of German Expressionist influence in Hollywood, as directors like Paul Leni, F.W. Murnau, and others brought their distinctive visual styles to American studios. The film's themes of class struggle and political corruption resonated with audiences during a period of increasing social awareness preceding the Great Depression. Universal Pictures was establishing itself as the premier horror studio, building on successes like 'The Hunchback of Notre Dame' and 'The Phantom of the Opera.' The film's release also coincided with the waning days of the Jazz Age, making its Gothic romance and social commentary particularly striking against the backdrop of Roaring Twenties excess.

Why This Film Matters

'The Man Who Laughs' holds a unique place in cinema history as a bridge between German Expressionism and American horror cinema. Its most enduring legacy is its influence on the creation of the Joker, Batman's arch-nemesis, with the character's iconic grin directly inspired by Conrad Veidt's performance. The film represents a pinnacle of silent horror filmmaking, showcasing how visual storytelling could convey complex emotions without dialogue. Its exploration of themes like otherness, social prejudice, and the nature of happiness has made it a subject of academic study in film courses worldwide. The movie also exemplifies the transition of horror from gothic romance to more psychologically complex narratives that would define the genre in subsequent decades. Its restoration and preservation have become important projects for film archivists, recognizing its significance in cinematic history.

Making Of

The production faced significant challenges in creating the iconic grin for Conrad Veidt's character. Makeup artist Jack Pierce (who later created Frankenstein's monster) developed a complex prosthetic using dental wire and rubber appliances that had to be applied daily for hours. Veidt's commitment to the role was extraordinary - he maintained the pained expression even when cameras weren't rolling, studying people with genuine facial deformities to perfect his performance. Director Paul Leni, known for his meticulous visual style, used innovative camera techniques including dramatic low angles and extensive use of shadows to enhance the Gothic atmosphere. The cast and crew worked in extreme conditions during the winter scenes, with artificial snow causing visibility issues. Mary Philbin, who played the blind Dea, wore special contact lenses that obscured her vision to authentically portray blindness, though this sometimes led to accidents on set.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Gilbert Warrenton and Hal Mohr showcases the German Expressionist influence that Paul Leni brought from Europe. The film employs dramatic chiaroscuro lighting, with deep shadows and stark contrasts creating a Gothic atmosphere that enhances the horror elements. Innovative camera techniques include sweeping crane shots during the carnival sequences and intimate close-ups that capture the emotional turmoil of the characters. The visual composition frequently uses angular set designs and distorted perspectives to reflect the psychological states of the characters. The film's color-tinted sequences (a common practice in silent films) use amber for warm scenes and blue for night or somber moments, adding emotional resonance to the black and white photography. The cinematography also makes effective use of deep focus to create layered compositions that emphasize the social hierarchies depicted in the story.

Innovations

The film pioneered several technical innovations in makeup effects, with Jack Pierce's prosthetic work on Conrad Veidt representing a breakthrough in creating realistic facial deformities for cinema. The production utilized the then-new Mitchell camera system, allowing for more fluid camera movements that enhanced the expressionistic visual style. The film's elaborate set designs, particularly the recreation of the House of Lords, showcased advances in studio construction techniques. The carnival sequences featured complex rigging systems for aerial shots and stunts. The film also experimented with multiple exposure techniques to create ghostly visual effects that enhanced the supernatural elements of the story. The preservation of the film's nitrate prints has demonstrated remarkable durability, with surviving elements showing excellent detail retention despite the medium's inherent instability.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Man Who Laughs' was originally accompanied by live musical performances in theaters. The original score was composed by William Axt and included themes that corresponded to different characters and emotional moments. Modern restorations have featured newly composed scores by contemporary musicians who specialize in silent film accompaniment. The most acclaimed modern score was composed by Donald Sosin in 2015, which premiered at the San Francisco Silent Film Festival. The music typically features dramatic orchestral arrangements that enhance the Gothic atmosphere, with leitmotifs for Gwynplaine's tragedy and the tender romance between Gwynplaine and Dea. The soundtrack's effectiveness in conveying emotion without dialogue has been praised by modern critics, demonstrating how well the film was constructed for musical accompaniment.

Famous Quotes

Why was I born if not to love you? - Gwynplaine to Dea

A man's face is his autobiography. A woman's face is her work of fiction. - Opening title card

Compassion is a luxury of the powerful. - Lord Clancharlie

The world is a comedy to those that think, a tragedy to those that feel. - Intertitle

I am not a monster. I am a man. - Gwynplaine

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence showing the execution of Lord Clancharlie and the abandonment of his son in the snow

- The horrifying scene of young Gwynplaine being surgically given his permanent grin by Dr. Hardquanonne

- Gwynplaine's first performance as 'The Man Who Laughs' in the carnival, where the audience's laughter turns to horror

- The tender scene where blind Dea touches Gwynplaine's face, feeling his 'smile' without seeing its grotesque nature

- Gwynplaine's dramatic entrance into the House of Lords, where his appearance shocks the aristocrats

- The final scene on the ship where Gwynplaine and Dea embrace, finding acceptance and love away from society

Did You Know?

- Conrad Veidt's portrayal of Gwynplaine with the permanent grin directly inspired the creation of the Joker character in Batman comics, with Jerry Robinson and Bill Finger citing the film as a major influence.

- The prosthetic makeup used on Veidt was so uncomfortable that he could only eat liquids between takes and suffered from jaw pain throughout the production.

- Director Paul Leni was a prominent figure in German Expressionist cinema before moving to Hollywood, and this film was considered his American masterpiece.

- Mary Philbin also starred in 'The Phantom of the Opera' (1925) opposite Lon Chaney, making her one of the few actresses to star in two major horror films of the silent era.

- The film was based on Victor Hugo's 1869 novel 'L'Homme qui rit,' which Hugo wrote as a critique of aristocratic privilege and social injustice.

- Universal Carl Laemmle Jr. personally greenlit the expensive production, believing it could replicate the success of their earlier horror hits.

- The original cut was reportedly longer, but several scenes were trimmed for release, including some political content that might have been controversial.

- The film's European premiere was delayed due to concerns about its political themes criticizing monarchy.

- A sound version was briefly considered but abandoned as Universal felt the story worked better as a silent film.

- The film was one of the last major silent horror productions before the transition to sound.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film's visual artistry and Conrad Veidt's powerful performance, with many reviews highlighting Paul Leni's masterful direction and atmospheric cinematography. The New York Times called it 'a remarkable achievement in silent cinema' and noted Veidt's 'haunting portrayal of a man cursed by his appearance.' Modern critics have reevaluated the film as a masterpiece of silent horror, with Rotten Tomatoes showing a 92% approval rating from critics. Film historians often cite it as one of the most artistically successful Universal horror productions of the silent era. The film's visual style has been extensively analyzed in academic papers on German Expressionism's influence on American cinema. Recent reviews have emphasized its relevance to contemporary discussions about appearance-based discrimination and social alienation.

What Audiences Thought

Initial audience response was mixed, with some viewers finding the film's tone too dark and Veidt's appearance unsettling, while others were captivated by the tragic romance story. The film performed moderately well at the box office, particularly in urban areas where art-house cinema was appreciated. Over time, the film has developed a cult following among classic horror enthusiasts and silent film aficionados. Modern audiences who discover the film often express surprise at its emotional depth and visual sophistication, with many noting how effectively it conveys complex emotions without dialogue. The film has gained renewed interest through its connection to the Joker character, attracting Batman fans to silent cinema. Film festival screenings in recent decades have shown that contemporary audiences respond strongly to its themes of acceptance and love transcending physical appearance.

Awards & Recognition

- No major awards were won, as the film was released before the Academy Awards expanded to include many technical categories

Film Connections

Influenced By

- German Expressionist cinema

- Victor Hugo's novel 'L'Homme qui rit'

- The works of F.W. Murnau

- Universal's earlier horror productions like 'The Hunchback of Notre Dame'

- Gothic literature tradition

- Commedia dell'arte character archetypes

This Film Influenced

- Batman (through the Joker character)

- Freaks (1932)

- The Phantom of the Opera (various adaptations)

- Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street

- The Elephant Man

- The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1939)

- Beauty and the Beast (various adaptations)

- The Dark Knight (Joker's visual design)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved by the Universal Studios film archives and the Library of Congress. A restoration was completed in the 1970s, and a more comprehensive digital restoration was undertaken in 2015 by Universal in collaboration with film preservation organizations. The film survives in its complete form with excellent image quality, though some minor deterioration is visible in certain scenes. The restoration has made the film available on Blu-ray and for theatrical screenings at film festivals. The preservation effort included finding the original camera negatives and combining them with the best available print elements to create the most complete version possible.