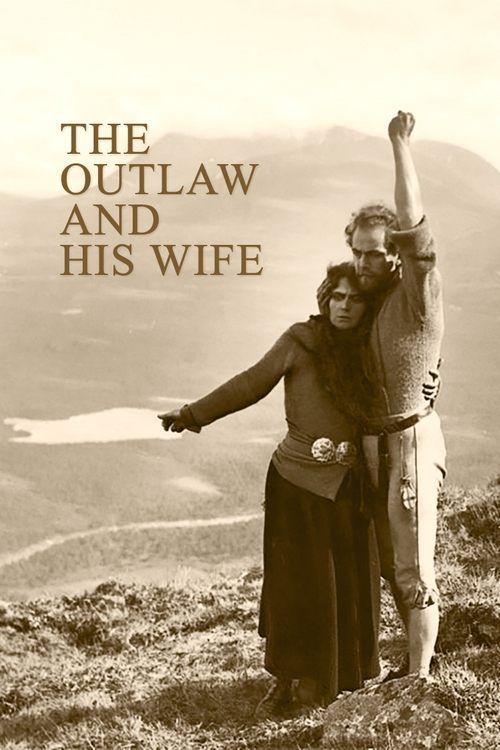

The Outlaw and His Wife

Plot

Halla, a wealthy widow living on a remote Icelandic farm, hires a mysterious stranger named Eyvind to work on her property. Despite initial reservations, they fall deeply in love and marry. However, their happiness is shattered when it's revealed that Eyvind is actually an infamous escaped thief who was forced into crime to save his starving family. When authorities arrive to arrest him, Halla makes the fateful decision to abandon her comfortable life and flee with him into the harsh Icelandic mountains. They join a community of outlaws living in the wilderness, facing brutal weather, starvation, and the constant threat of capture. Their love is tested by extreme hardship, betrayal by fellow outlaws, and the moral compromises required for survival, ultimately leading to a tragic climax where Halla sacrifices herself to save Eyvind during a blizzard, leaving him to face his fate alone.

About the Production

The film was shot during the summer of 1917 in extreme weather conditions. The production team faced significant challenges filming in the Swedish mountains, with cast and crew enduring harsh conditions to achieve authentic location shots. Director Victor Sjöström insisted on filming in actual wilderness rather than using studio sets, which was revolutionary for the time. The film's spectacular mountain sequences were achieved through dangerous location photography, with the crew carrying heavy equipment through difficult terrain.

Historical Background

The Outlaw and His Wife was produced during the final year of World War I, a period when neutral Sweden had become a major force in international cinema. While European film industries were devastated by the war, Sweden's studios thrived, producing sophisticated films that found eager audiences worldwide. This film emerged during what critics later called the 'Golden Age of Swedish Cinema' (1917-1924), characterized by psychological depth, naturalistic acting, and innovative use of landscape. The film's themes of outcast morality and the conflict between individual desire and social order resonated with post-war audiences questioning traditional values. Its production coincided with the Russian Revolution and the collapse of old European empires, making its story of characters forced outside society particularly relevant to contemporary audiences.

Why This Film Matters

The Outlaw and His Wife represents a pivotal moment in cinema history, demonstrating how film could achieve the artistic depth of literature while utilizing the unique visual language of the medium. The film's innovative use of landscape as a psychological element influenced generations of filmmakers, particularly in how natural environments could reflect characters' internal states. It helped establish the Scandinavian tradition of melancholic, nature-focused cinema that would later influence directors like Ingmar Bergman. The film's international success proved that art cinema could find commercial success outside Hollywood, encouraging other national cinemas to pursue artistic ambition. Its blend of romantic melodrama with philosophical questions about morality and redemption created a template for the art film genre that would flourish throughout the 20th century.

Making Of

The production of 'The Outlaw and His Wife' was groundbreaking for its time, representing a shift away from studio-bound filmmaking toward location shooting that captured the raw power of nature. Director Victor Sjöström, a pioneer of Swedish cinema, demanded authenticity in every aspect of the production. The cast and crew spent weeks in the harsh Swedish mountains, filming in extreme weather conditions that were not simulated. Sjöström developed innovative camera techniques to capture the vast landscapes, including long shots that emphasized the characters' vulnerability against nature. The relationship between Sjöström and Erastoff developed during filming and culminated in their marriage, adding authenticity to their on-screen chemistry. The film's production was part of what would later be recognized as the golden age of Swedish cinema (1917-1924), when Swedish films gained international recognition for their artistic quality and technical innovation.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Julius Jaenzon was revolutionary for its time, featuring extensive location photography in the Swedish mountains that captured the raw power and beauty of nature. Jaenzon employed innovative techniques including deep focus photography, dramatic contrasts between light and shadow, and sweeping panoramic shots that emphasized the isolation of the characters. The film's visual style uses the landscape as a psychological mirror, with the harsh, unforgiving mountains reflecting the moral wilderness inhabited by the outlaws. The cinematography achieves remarkable naturalism while maintaining a poetic quality, particularly in scenes where characters are dwarfed by their surroundings. The technical achievement of capturing these images with 1918 camera equipment in extreme weather conditions remains impressive to this day.

Innovations

The film broke new ground in several technical areas, most notably in its extensive use of location photography in extreme conditions. The production team developed special equipment to protect cameras and film from the cold, and created innovative camera mounts for filming on mountain slopes. The film features some of the earliest examples of what would later be called 'psychological editing,' using cuts and camera movements to reflect characters' emotional states. The lighting techniques, particularly in the mountain scenes, achieved remarkable naturalism while maintaining dramatic effect. The film's preservation and restoration in the 21st century also represented technical achievements in digital restoration of deteriorated nitrate film stock.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Outlaw and His Wife' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The typical score would have been provided by a theater organist or small orchestra, often using classical pieces adapted to fit the mood of each scene. Modern screenings of restored versions typically feature newly composed scores, with notable versions including music by Swedish composer Matti Bye. The original cue sheets, if they existed, have not survived, so contemporary musicians create their own interpretations based on the film's emotional arc and visual rhythm. The score traditionally emphasizes the film's Nordic setting with folk-inspired melodies during pastoral scenes and dramatic, dissonant passages during moments of conflict and tragedy.

Famous Quotes

"Better to die in the mountains with love than live without it." (intertitle)

"The law of men is not the law of God." (intertitle)

"In the wilderness, we are all equal before nature." (intertitle)

"Love makes criminals of us all, or saints." (intertitle)

Memorable Scenes

- The wedding scene in the remote farm chapel, where Halla and Eyvind exchange vows amidst the vast Icelandic landscape, symbolizing their union against the forces of society and nature.

- The desperate flight through the mountain pass as authorities close in, with the couple silhouetted against the snow-covered peaks in a sequence that combines breathtaking cinematography with heart-pounding suspense.

- The final sacrifice scene where Halla gives herself to the blizzard to save Eyvind, her body gradually disappearing into the white landscape in one of cinema's most poetic and tragic death scenes.

Did You Know?

- The original Swedish title 'Berg-Ejvind och hans hustru' translates to 'Mountain-Eyvind and His Wife'

- Based on a play by Icelandic playwright Jóhann Sigurjónsson, which itself was based on an Icelandic folk tale

- Victor Sjöström both directed and starred in the film, playing the lead role of Eyvind

- The film was a major international success and helped establish Swedish cinema's reputation in the 1910s

- Edith Erastoff, who played Halla, married Victor Sjöström the same year the film was released

- The mountain scenes were filmed in Abisko, Sweden, above the Arctic Circle, in sub-zero temperatures

- The film was one of the first to use natural landscapes as a central character in the narrative

- A restored version was completed in 2018 by the Swedish Film Institute to celebrate the film's 100th anniversary

- The film's success led to Sjöström being recruited by Hollywood, where he later directed major films including 'He Who Gets Slapped' (1924)

- The original negative was thought lost for decades but was discovered in the 1970s in a film archive

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics hailed the film as a masterpiece, with particular praise for its stunning cinematography and powerful performances. The New York Times called it 'one of the most remarkable films ever produced' upon its American release in 1920. Critics noted the film's unprecedented use of natural scenery not merely as background but as an active force in the drama. Modern critics continue to celebrate the film; in the 2012 Sight & Sound poll, it was ranked among the greatest films ever made. The film is particularly praised for its sophisticated narrative structure, psychological depth, and the way it transcends the melodramatic conventions of its era. Film historian Peter Cowie has called it 'perhaps the supreme achievement of the Swedish silent period,' noting its influence on subsequent European art cinema.

What Audiences Thought

The film was enormously popular with audiences upon its release, both in Sweden and internationally. Its combination of romance, adventure, and spectacular scenery appealed to a wide range of viewers. Contemporary audience reports describe emotional reactions to Halla's sacrifice, with many viewers reportedly weeping during the final scenes. The film's success at the box office helped establish Svenska Biografteatern as one of Europe's leading production companies. Despite its age, the film continues to move modern audiences when screened at film festivals and retrospectives, with its themes of love, sacrifice, and the struggle against nature remaining universally resonant.

Awards & Recognition

- Best Film of 1918 - Swedish Film Critics Association (retrospective award)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Icelandic Folk Tales

- Plays by Jóhann Sigurjónsson

- Swedish Literary Tradition

- Nordic Mythology

- Romantic Literature

- Naturalist Movement in Arts

This Film Influenced

- The Wind (1928)

- Way Down East (1920)

- The Song of the Scarlet Flower (1919)

- Wild Strawberries (1957)

- The Seventh Seal (1957)

- Days of Heaven (1978)

- The Revenant (2015)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has survived in relatively good condition for its age, with original elements held by the Swedish Film Institute. A major restoration was completed in 2018 for the film's centenary, using the best available elements from international archives. The restoration involved digital cleaning and color grading to approximate the original tinting schemes. While some scenes show signs of deterioration, the film remains largely complete and viewable. The restored version has been screened at major film festivals including Cannes and Venice, bringing this masterpiece to new audiences.