The Shriek of Araby

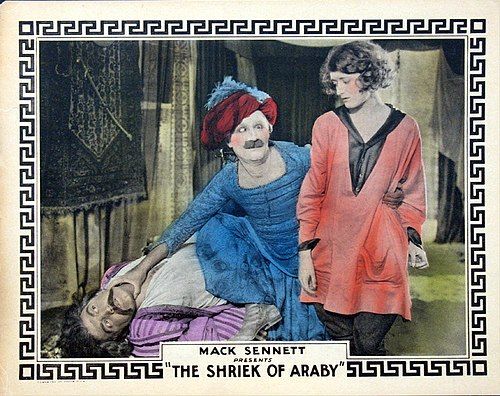

"The Comedy Sensation of the Year! A Hilarious Take-Off on 'The Sheik'!"

Plot

Ben Turpin plays a theater usher who becomes completely captivated while watching Rudolph Valentino's blockbuster film 'The Sheik.' During the screening, he drifts into an elaborate daydream where he imagines himself as the dashing Arab sheik, complete with flowing robes and dramatic romantic encounters. In his fantasy world, he pursues a beautiful princess (Kathryn McGuire) while battling rival suitors and navigating various comedic misadventures in the desert. The film cleverly interweaves reality and fantasy, showing the usher's increasingly outrageous daydreams contrasted with his mundane reality back at the theater. The parody reaches its climax when his dreams become so vivid that he begins acting out the scenes in real life, much to the confusion of the movie patrons and his fellow employees.

About the Production

This film was part of Mack Sennett's strategy to capitalize on popular trends through parody. The production used existing sets from other productions to save costs. Ben Turpin's famous crossed eyes were emphasized for comedic effect throughout the film. The desert sequences were created using painted backdrops and creative camera angles to simulate Arabian landscapes without leaving California.

Historical Background

The film was produced during the peak of the silent era's golden age, when Hollywood was churning out films at an unprecedented rate. 1923 was a significant year in cinema, marking the transition from short films to feature-length productions as the industry standard. The 'Arabian craze' had swept America following Valentino's 'The Sheik,' influencing fashion, music, and popular culture. This film represents the industry's tendency to quickly capitalize on trends through parody and imitation. The early 1920s also saw the rise of movie palaces and the establishment of cinema as America's primary entertainment medium. Comedy shorts like this were crucial components of theater programs, often serving as appetizers before the main feature.

Why This Film Matters

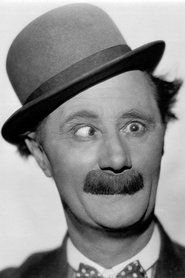

This film represents an important example of early Hollywood's parody tradition, demonstrating how quickly the industry could respond to and capitalize on cultural phenomena. It showcases the art of the movie parody, a genre that would become increasingly sophisticated throughout cinema history. The film also highlights the career of Ben Turpin, one of the silent era's most recognizable comic actors, whose crossed eyes became his trademark. As a satire of Valentino's exotic romanticism, it reflects American attitudes toward foreign cultures and the romanticization of the 'Orient' in the 1920s. The movie also serves as a time capsule of movie theater culture in the early 1920s, showing how films were exhibited and experienced by audiences of the period.

Making Of

The production was typical of Mack Sennett's fast-paced comedy factory approach. F. Richard Jones, a veteran Sennett director, worked quickly to complete the film in just a few days. The cast rehearsed minimally, relying on their established comic personas and improvisation skills. Ben Turpin, known for his professionalism, arrived on set with his own costume ideas to enhance the parody effect. The theater sequences were filmed first, using actual Sennett employees as extras to create authenticity. The desert fantasy sequences required creative solutions - the production team used smoke machines, wind machines, and carefully placed palm fronds to create the illusion of an Arabian desert. The film's editing was particularly innovative for its time, using quick cuts between reality and fantasy to emphasize the comedic contrast.

Visual Style

The cinematography, typical of Sennett productions, was functional but effective. The camera work employed basic techniques of the era including close-ups for comic effect, medium shots for dialogue scenes, and wide shots for the fantasy sequences. The cinematographer used lighting to create dramatic contrast between the mundane theater scenes and the romanticized desert sequences. The desert scenes utilized special filters and careful lighting to simulate the harsh Middle Eastern sun. The film also made effective use of the iris shot technique, popular in silent films, to focus audience attention on specific gags or reactions. The camera movement was minimal, as was typical for comedy shorts of the period, relying instead on staging and performance to create visual interest.

Innovations

While not groundbreaking technically, the film demonstrated efficient use of existing technology and techniques. The seamless transitions between reality and fantasy sequences were accomplished through clever editing and camera techniques. The production team created convincing desert environments using minimal resources, showcasing the ingenuity of silent era filmmakers. The film also employed effective use of superimposition for some of the dream sequence effects. The makeup and costume departments deserve credit for creating convincing parodies of Arabian costumes while maintaining the comedic tone. The film's pacing, achieved through editing, represents the sophisticated understanding of comic timing that had developed in Hollywood by the early 1920s.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Shriek of Araby' would have been accompanied by live musical performance in theaters. The score would typically have been compiled from various classical pieces and popular songs of the era, with theater organists or small orchestras improvising based on cue sheets provided by the studio. For the parody elements, musicians might have used dramatic Arabian-themed music during the fantasy sequences, contrasting with jaunty, comedic tunes for the reality scenes. The film likely included sound effects created by theater musicians using various instruments and noisemakers to enhance the comedy. No original composed score exists for this film, as was standard practice for short comedies of the period.

Famous Quotes

(Intertitle) 'When the Sheik appears on screen, even ushers become dreamers!'

(Intertitle) 'In his dreams, every man can be a Valentino!'

(Intertitle) 'Reality is a movie palace... Fantasy is an Arabian desert!'

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence showing Turpin as the theater usher, completely mesmerized by 'The Sheik' on screen, his crossed eyes comically wide with wonder

- The transition scene where Turpin falls asleep and his chair transforms into a magic carpet, carrying him into his Arabian fantasy

- The parody of the famous Valentino romantic scenes, with Turpin attempting to be suave and mysterious while his crossed eyes undermine his efforts

- The chase sequence through the 'desert' where Turpin, in full sheik costume, comically battles rival suitors for the princess's hand

- The final scene where Turpin is awakened by his angry theater manager, still partially in character as the sheik

Did You Know?

- The title is a clever pun on 'The Shriek' instead of 'The Sheik,' emphasizing the comedy aspect

- Ben Turpin was one of the highest-paid comedians of the silent era, earning up to $3,000 per week at his peak

- The film was rushed into production to capitalize on the massive success of Valentino's 'The Sheik' (1921) and its sequel 'The Son of the Sheik' (1926)

- Mack Sennett was famous for producing quick parodies of hit films, often releasing them within months of the original's success

- Kathryn McGuire was a regular Sennett player who also appeared in Buster Keaton's 'The Navigator' (1924)

- The film's release coincided with the height of 'sheik-mania' in American popular culture

- George Cooper was often cast as Turpin's straight man in Sennett comedies

- The theater scenes were filmed on actual Sennett studio sets designed to resemble movie palaces of the era

- This was one of the last films Turpin made for Sennett before his contract disputes began

- The film's poster featured Turpin in exaggerated Arab costume with his crossed eyes prominently displayed

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics generally praised the film as an effective parody, with Variety noting Turpin's 'hilarious interpretation of the Valentino persona.' The Motion Picture News called it 'a splendid two-reel comedy that capitalizes cleverly on the current sheik craze.' Modern critics and film historians view it as a typical but well-executed example of Sennett's rapid-fire comedy production style. While not considered a masterpiece of silent comedy, it's valued today for its historical significance as a parody of one of the most influential films of the 1920s. Film historian Kevin Brownlow has noted that while the film may seem simple by modern standards, it represents the sophisticated humor that could be conveyed through purely visual means in the silent era.

What Audiences Thought

The film was well-received by contemporary audiences who were familiar with 'The Sheik' and could appreciate the parody elements. Theater audiences of the 1920s loved seeing popular films and stars spoofed, and Turpin's recognizable face and comic timing made the short a reliable crowd-pleaser. The film performed particularly well in urban areas where moviegoers were more likely to have seen Valentino's original. Audience members reportedly laughed especially hard at the contrast between Turpin's comical appearance and his attempts to mimic Valentino's romantic intensity. The film's success led to increased demand for similar parodies, though few matched the effectiveness of this particular send-up.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The Sheik (1921)

- Mack Sennett comedy style

- Slapstick comedy tradition

- Arabian Nights literature

- Valentino's romantic persona

This Film Influenced

- Later Hollywood parodies of hit films

- Sennett's subsequent trend-based comedies

- Airplane! (1980) - as part of the parody tradition

- The Naked Gun series - continuing the spoof genre

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is partially preserved. While not completely lost, some elements may be missing or deteriorated. Prints exist in several film archives including the Library of Congress and the UCLA Film & Television Archive. The available versions show varying degrees of deterioration typical of nitrate film from the 1920s. Some restoration work has been done, but the film has not received a comprehensive digital restoration. The preservation status represents the fortunate survival of many Sennett comedies, though some remain lost.