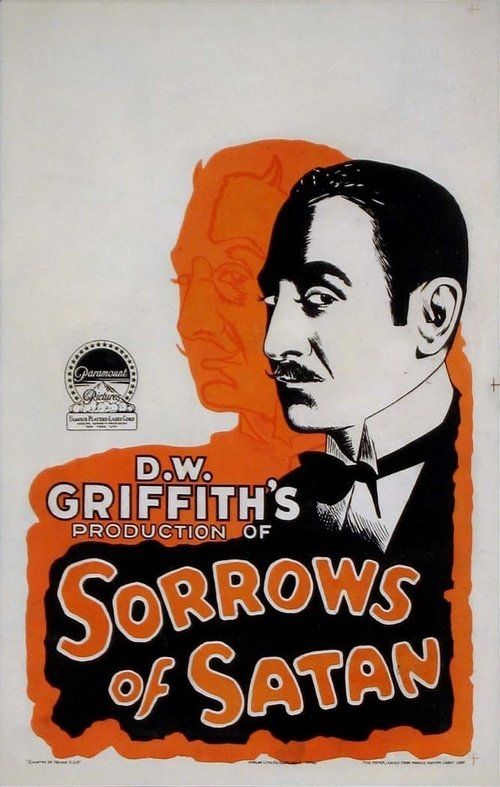

The Sorrows of Satan

"The Master Director's Greatest Triumph of Spectacle and Drama!"

Plot

Geoffrey, a struggling writer living in a boardinghouse, is desperately in love with fellow resident Mavis but cannot marry her due to his poverty. In a moment of despair, he curses God for abandoning him. Shortly after, he encounters the wealthy and sophisticated Prince Lucio de Rimanez, who reveals that Geoffrey has inherited a fortune but must place himself under the Prince's guidance to enjoy it. Unbeknownst to Geoffrey, Prince Lucio is actually Satan, and as Geoffrey indulges in his newfound wealth and success, he becomes entangled in a web of temptation, moral compromise, and spiritual conflict. The film follows Geoffrey's journey from poverty to luxury, his moral deterioration, and eventual realization that he has made a pact with the devil, forcing him to choose between earthly pleasures and eternal salvation.

About the Production

This was D.W. Griffith's first film for Paramount Pictures after leaving United Artists. The production featured elaborate sets including opulent ballrooms, luxurious mansions, and spectacular party scenes. Griffith spared no expense in creating visual spectacle, employing hundreds of extras for crowd scenes. The film's special effects, particularly for supernatural elements, were considered advanced for the time. Griffith worked closely with cinematographer Hendrik Sartov to achieve a more sophisticated visual style than his earlier works.

Historical Background

The Sorrows of Satan was produced during a pivotal transitional period in American cinema. 1926 was the year before 'The Jazz Singer' would revolutionize the industry with sound, and silent filmmakers were desperately trying to innovate visually to maintain audience interest. The film reflected the moral complexities of the Roaring Twenties, a period of unprecedented prosperity, changing social mores, and underlying spiritual anxiety. Griffith, once the undisputed master of American cinema, was struggling to maintain his relevance in an industry that was rapidly moving away from his Victorian sensibilities. The film's exploration of wealth, temptation, and moral compromise resonated with contemporary concerns about materialism and the American Dream. It was also made during the height of the studio system's power, when independent producers like Griffith were being squeezed out by major studios.

Why This Film Matters

The Sorrows of Satan represents an important but often overlooked chapter in American film history as one of the last major silent epics. It demonstrates D.W. Griffith's attempt to adapt his filmmaking style to the more sophisticated tastes of 1920s audiences, moving away from the moral simplicity of his earlier works like 'The Birth of a Nation' and 'Intolerance'. The film's exploration of religious themes through the lens of modern materialism reflects the cultural tensions of the Jazz Age. Its commercial failure signaled the end of Griffith's dominance in American cinema and highlighted the industry's shift toward more contemporary storytelling styles. The film also represents one of the earliest major Hollywood productions to deal directly with satanic themes, predating later films that would explore similar territory. Its preservation and restoration have been important for film scholars studying the transition from Griffith's pioneering early work to the more mature Hollywood studio system.

Making Of

The production of 'The Sorrows of Satan' was marked by both ambition and tension. Griffith, determined to prove he could still compete in the changing film landscape of the 1920s, pushed for unprecedented visual effects and set designs. The relationship between Griffith and Carol Dempster, both personal and professional, created some tension on set, particularly with other cast members. Adolphe Menjou, a seasoned professional by this time, reportedly had creative differences with Griffith over his interpretation of the Satan character, wanting to make him more charming and less overtly evil. The film's extensive party scenes required weeks of rehearsal and involved some of Hollywood's most expensive extras. Griffith experimented with new camera techniques, including complex tracking shots and innovative lighting effects to create the supernatural atmosphere. The production ran over budget and behind schedule, causing friction with Paramount executives who were already nervous about the film's commercial prospects.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Hendrik Sartov represented a significant evolution from Griffith's earlier work with Billy Bitzer. Sartov employed more sophisticated lighting techniques, including dramatic use of shadows to create atmosphere in the supernatural sequences. The film featured elaborate tracking shots and complex camera movements that were technically advanced for the time. The party sequences utilized multiple cameras and innovative angles to capture the scale and decadence of the settings. Sartov's work emphasized the contrast between the earthly opulence and spiritual darkness, using lighting and composition to reinforce the film's themes. The cinematography was praised for its technical polish even by critics who disliked the film itself.

Innovations

The film featured several technical innovations for its time, including sophisticated special effects to create supernatural phenomena. The production employed advanced matte painting techniques for elaborate background scenes. The film's editing was more fluid than much of Griffith's earlier work, showing his adaptation to contemporary pacing. The soundstage construction for the film's interior sets was among the most ambitious of the silent era. The costume department developed new techniques for creating period-appropriate fabrics and accessories. The film's lighting setup was particularly complex, requiring innovative solutions to achieve the desired contrast between the earthly and supernatural elements.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Sorrows of Satan' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The score was likely compiled from classical pieces and popular music of the era, adapted to match the film's dramatic needs. Paramount would have provided cue sheets to theater musicians indicating appropriate music for different scenes. The film's supernatural elements would have called for dramatic, often dissonant musical passages during the satanic sequences, while romantic scenes would have featured more lyrical compositions. No original composed score survives, and modern screenings typically use newly commissioned scores or compilations of period-appropriate music.

Famous Quotes

I am Prince Lucio de Rimanez. I have come to offer you everything your heart desires.

God has abandoned you, but I never abandon those who seek power.

What is wealth without the power to enjoy it? What is love without the means to possess it?

Every soul has its price, and I am prepared to pay yours.

The path to salvation is narrow, but the road to damnation is paved with gold.

Memorable Scenes

- The elaborate masquerade ball where Geoffrey first experiences the decadent lifestyle Prince Lucio offers him, featuring hundreds of extras in extravagant costumes and sophisticated camera movements through the crowded ballroom.

- The supernatural confrontation scene where Prince Lucio reveals his true identity to Geoffrey, utilizing innovative special effects and dramatic lighting to create an otherworldly atmosphere.

- The final moral choice sequence where Geoffrey must decide between earthly pleasures with Mavis or spiritual redemption, intercutting visions of both possibilities.

Did You Know?

- This was D.W. Griffith's most expensive film to date, costing over half a million dollars

- The film was based on Marie Corelli's 1895 bestselling novel 'The Sorrows of Satan', which had been controversial for its time

- Adolphe Menjou's portrayal of Satan was considered one of his finest performances, though it was somewhat overshadowed by his later sound films

- Carol Dempster, who played Mavis, was Griffith's protégée and personal companion, and this was one of her final major film roles

- The film featured elaborate costume design with over 1,000 costumes created specifically for the production

- Griffith originally wanted to make this film in the early 1920s but couldn't secure financing until Paramount offered him a deal

- The film's failure at the box office marked a significant turning point in Griffith's career, accelerating his decline as a major director

- Despite its commercial failure, the film was praised for its technical achievements and visual spectacle

- The original negative was believed lost for decades before being rediscovered and partially restored

- Griffith considered this film his personal favorite among his later works

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception was mixed to negative. Many critics felt that Griffith had lost touch with modern audiences, with some reviews describing the film as old-fashioned and melodramatic. The New York Times criticized its excessive moralizing while acknowledging its technical achievements. Variety noted that despite spectacular production values, the story lacked the emotional impact of Griffith's earlier works. Modern reassessments have been more charitable, with film historians recognizing the film's artistic merits and its importance in understanding Griffith's career trajectory. Critics today appreciate the film's visual sophistication and Menjou's performance, though most agree it doesn't rank among Griffith's greatest achievements. The film is now studied as an example of late silent cinema's ambitions and limitations.

What Audiences Thought

Audience reception in 1926 was largely disappointing, contributing to the film's box office failure. Contemporary moviegoers, accustomed to the faster pace and more cynical tone of 1920s cinema, found Griffith's moralistic approach somewhat dated. The film's length and deliberate pacing tested the patience of some viewers. However, those who appreciated spectacle and grandeur were impressed by the production values and set designs. The film developed a cult following among silent film enthusiasts in later decades, with modern audiences showing renewed interest in its visual artistry and historical significance. Today, it's primarily viewed by film scholars and classic cinema devotees who appreciate its place in film history.

Awards & Recognition

- No major awards were won by this film

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Marie Corelli's novel 'The Sorrows of Satan' (1895)

- Goethe's 'Faust'

- Oscar Wilde's 'The Picture of Dorian Gray'

- Griffith's earlier moral epics like 'Intolerance'

This Film Influenced

- The Devil's Holiday (1930)

- Angel Heart (1987)

- The Devil's Advocate (1997)

- Bedazzled (1967 and 2000)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was believed lost for many years but a complete 35mm print was discovered in the 1970s. The film has been partially restored by film archives, though some sequences remain damaged. The restored version is available through select film archives and specialty distributors. The preservation status is considered stable, with copies held at major film archives including the Library of Congress and the Museum of Modern Art.