Twelfth Night

Plot

In this early adaptation of Shakespeare's comedy, twins Viola and Sebastian are separated during a violent shipwreck, each believing the other has perished. Viola washes ashore in Illyria and, fearing for her safety in a foreign land, disguises herself as a young man named Cesario and enters the service of Duke Orsino. The Duke, pining for the Countess Olivia, sends Cesario to plead his case, but Olivia falls deeply in love with the disguised Viola. Complications escalate when Sebastian, who has also survived, arrives in Illyria, creating mistaken identities, romantic confusion, and ultimately a joyful resolution as the twins are reunited and true love finds its proper course.

About the Production

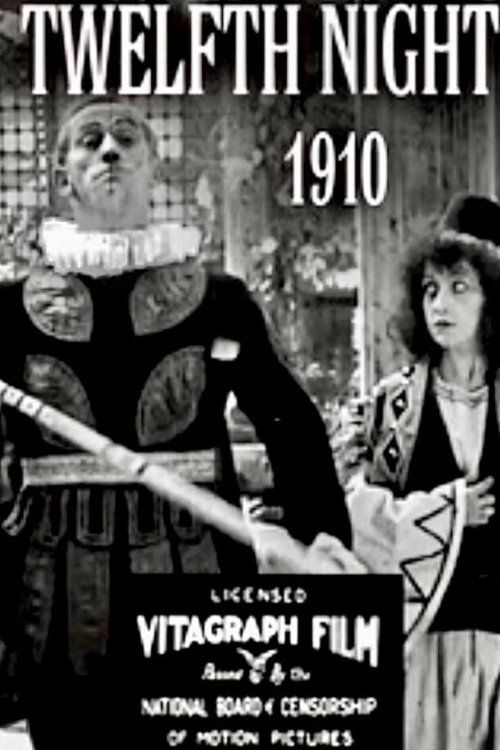

This was one of the earliest film adaptations of Shakespeare's work, produced during the pioneering era of American cinema. The film was created at Vitagraph's open-air studio in Brooklyn, utilizing natural lighting as artificial lighting technology was still primitive. The production faced the typical challenges of early cinema including the need for exaggerated acting to convey emotion without dialogue, and the technical limitations of cameras that could only film for short periods before needing to be reloaded.

Historical Background

This film was produced during the early years of American cinema's transition from novelty to art form. In 1910, the film industry was still establishing its language and conventions, with most films being short, simple narratives. The decision to adapt Shakespeare represented an ambitious attempt to legitimize cinema as a medium capable of handling sophisticated literary material. This period also saw the rise of the star system, with Florence Turner being one of the first actors to be promoted by name. The film emerged just as the Motion Picture Patents Company (the Edison Trust) was beginning to lose its monopoly on film production, allowing independent studios like Vitagraph to flourish. It was also a time when films were transitioning from vaudeville-style attractions to standalone theatrical presentations.

Why This Film Matters

As one of the earliest Shakespearean adaptations in American cinema, this film helped establish the precedent for bringing classical literature to the screen. It demonstrated that complex plots and sophisticated themes could be conveyed through the visual medium of silent film, paving the way for future literary adaptations. The film's success contributed to the growing acceptance of cinema as a legitimate art form rather than mere entertainment. It also helped solidify Florence Turner's status as America's first true movie star, influencing the development of the celebrity culture that would become central to Hollywood. The adaptation showed early audiences that familiar stories could be reimagined through film, helping to bridge the gap between traditional theater and the new medium of cinema.

Making Of

The production of 'Twelfth Night' took place during a transformative period in American cinema when studios were beginning to recognize the commercial potential of literary adaptations. Eugene Mullin, both director and adapter, faced the challenge of condensing Shakespeare's complex plot into a 12-minute runtime while maintaining the essence of the comedy. The cast, all Vitagraph regulars, were accustomed to the exaggerated acting style required for silent films, where facial expressions and body language had to convey what dialogue would in a stage production. The film was shot outdoors at Vitagraph's Brooklyn studio to take advantage of natural sunlight, as indoor lighting technology was still in its infancy. Makeup was applied heavily to ensure actors' features were visible on the relatively insensitive film stock of the era.

Visual Style

The cinematography, typical of the Vitagraph style of 1910, utilized static camera positions with careful composition to frame the actors and convey the narrative. The film was shot in natural light, which created soft, diffused illumination characteristic of outdoor filming of this era. The camera work was functional rather than artistic, focusing on ensuring the actors' performances were clearly visible. Long takes were employed to minimize editing, which was still a relatively primitive process. The visual style emphasized clarity and legibility over aesthetic innovation, reflecting the primary goal of early narrative cinema to tell stories comprehensibly. The use of medium shots allowed for the recognition of facial expressions and gestures crucial to silent film performance.

Innovations

While not technically innovative by modern standards, the film represented several achievements for its era. The successful adaptation of a complex Shakespearean plot into a 12-minute format demonstrated emerging skills in cinematic narrative compression. The production utilized Vitagraph's improved film stock, which offered better image quality than earlier films. The costume design successfully evoked Elizabethan period detail while accommodating the practical needs of film production. The film's editing, though simple by today's standards, showed growing sophistication in maintaining narrative continuity across scenes. The use of intertitles to convey essential plot points and dialogue represented an important development in silent film storytelling techniques.

Music

As a silent film, 'Twelfth Night' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during theatrical exhibition. The typical accompaniment would have consisted of a pianist or small ensemble playing appropriate classical and popular pieces selected to match the mood of each scene. Vitagraph often provided musical cue sheets with their films, suggesting specific pieces for theaters to use. For a Shakespeare adaptation, the music likely included selections from classical composers and possibly period-appropriate melodies. The score would have emphasized the comedic elements with lighter, more playful music during scenes of mistaken identity, while using more romantic themes for the love scenes. The musical accompaniment was essential for conveying emotional tone and narrative pacing in the absence of recorded sound.

Famous Quotes

'I am not what I am' - Viola (as Cesario)

'If music be the food of love, play on' - Duke Orsino

'Some are born great, some achieve greatness, and some have greatness thrust upon them' - Malvolio

'Love sought is good, but given unsought is better' - Olivia

Memorable Scenes

- The opening shipwreck sequence establishing the separation of the twins

- Viola's transformation into Cesario and her introduction to Duke Orsino

- The first meeting between Olivia and the disguised Viola, where Olivia falls in love

- The final revelation scene where the twins are reunited and all identities are clarified

Did You Know?

- This was the first American film adaptation of Shakespeare's Twelfth Night, predating all other versions by several years.

- Florence Turner, who played Viola, was known as 'The Vitagraph Girl' and was one of America's first film stars, earning approximately $100 per week at a time when the average worker made $12 per week.

- Director Eugene Mullin was also a noted Shakespearean scholar who adapted several of the Bard's plays for the screen.

- The film was released as a split-reel, meaning it shared a reel with another short film to maximize theater programming efficiency.

- Charles Kent, who played Duke Orsino, was also a director at Vitagraph and directed over 100 films during his career.

- The entire production was completed in just two days, which was typical for short films of this era.

- This film was part of Vitagraph's prestigious 'Quality Films' series, which aimed to bring literary classics to the screen.

- The costumes were designed to evoke Elizabethan England while being practical for the physical demands of silent film acting.

- Julia Swayne Gordon, who played Olivia, was married to Vitagraph executive Harry A. Gant.

- The film was distributed internationally, with special title cards created for foreign markets.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film for its ambitious attempt to bring Shakespeare to the screen, with The Moving Picture World noting that 'the spirit of the Bard has been well captured in this Vitagraph production.' Critics of the era particularly commended Florence Turner's performance as Viola, describing her as 'captivating' and 'perfectly suited to the dual nature of the role.' The film was recognized as a technical achievement for its time, with reviewers noting the clarity of the storytelling despite the condensed runtime. Modern film historians view the adaptation as an important historical document that demonstrates the early cinema industry's aspirations toward cultural legitimacy, while acknowledging the limitations inherent in the technology and acting conventions of the period.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1910 responded enthusiastically to the film, which was considered a prestige production by Vitagraph. The familiarity of Shakespeare's story, combined with the growing popularity of Florence Turner, made the film a commercial success in the short film market. Contemporary theater-goers, who were still the primary audience for films, appreciated the connection to respected literary material. The film's release coincided with a period when audiences were becoming more sophisticated in their understanding of cinematic storytelling, and they were able to follow the complex plot of mistaken identities despite the absence of dialogue. The film was particularly popular in urban areas where Shakespeare's works were well-known, helping to establish cinema's appeal to middle-class and educated audiences.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- William Shakespeare's play 'Twelfth Night' (1601-1602)

- Stage traditions of Shakespearean performance

- Earlier literary adaptations in cinema

- Commedia dell'arte traditions of mistaken identity

This Film Influenced

- The 1914 Italian silent adaptation of Twelfth Night

- The 1922 German adaptation 'Was geschah in dieser Nacht?'

- Subsequent Shakespeare adaptations in early cinema

- The development of romantic comedy tropes in silent film

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is believed to be lost, as is common with the vast majority of films from this early period. The nitrate film stock used in 1910 was highly unstable, and many Vitagraph productions from this era have not survived. No complete copies are known to exist in major film archives such as the Library of Congress, the Museum of Modern Art, or the British Film Institute. Only still photographs and contemporary reviews remain to document the film's existence. This loss is representative of the broader crisis in early film preservation, with estimates suggesting that over 90% of American silent films have been lost.