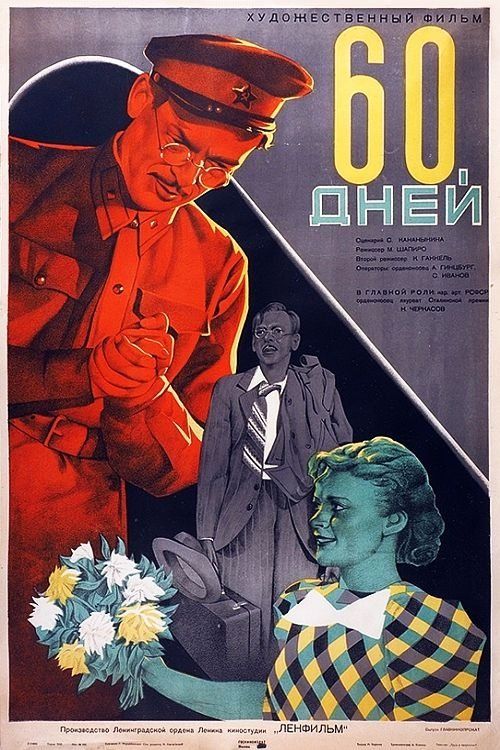

60 Days

"Even in wartime, laughter is the best medicine!"

Plot

Professor Zavadsky, a distinguished medical scientist, is called up for military reserve duty despite his advanced age and academic importance. During his 60-day service period, the absent-minded professor finds himself in numerous comical situations as he struggles to adapt to military discipline and routine. His scientific knowledge often clashes with military protocol, leading to misunderstandings and humorous encounters with commanding officers and fellow soldiers. The professor's unconventional approaches to military problems surprisingly yield positive results, earning him both respect and exasperation from his superiors. By the end of his service, Zavadsky has not only survived his military ordeal but has also contributed valuable medical innovations to the army, all while maintaining his endearing eccentricities.

About the Production

Remarkably filmed during the Siege of Leningrad, making this production particularly significant. The cast and crew worked under extreme conditions, with frequent air raids and shortages. Many scenes were shot in between bombing raids, and the film served as both entertainment and propaganda to boost civilian morale during one of the darkest periods of WWII. The production was evacuated from Leningrad to Moscow for completion due to worsening conditions.

Historical Background

Produced during the height of World War II, specifically during the brutal 900-day Siege of Leningrad (1941-1944), '60 Days' emerged as a testament to Soviet resilience and cultural determination. The film was created at a time when Leningrad was cut off from the rest of the Soviet Union, facing starvation, constant bombardment, and extreme cold. Cinema during this period served multiple purposes: entertainment for a suffering population, propaganda to maintain morale, and documentation of Soviet endurance. The comedy genre was particularly significant as it provided temporary escape from the horrors of war while reinforcing Soviet values of patriotism, sacrifice, and collective strength. The film's production itself became a symbol of cultural resistance, proving that even under the most adverse conditions, Soviet art and culture would not only survive but thrive.

Why This Film Matters

'60 Days' holds a unique place in Soviet cinema history as one of the few comedies produced during the darkest period of WWII. It demonstrated that humor could coexist with patriotism and that even in times of extreme crisis, the human spirit could find reasons to laugh. The film's portrayal of an intellectual serving his country helped bridge the gap between Soviet academia and the military, reinforcing the idea that all citizens had a role to play in the war effort. Its success paved the way for more sophisticated wartime comedies that balanced entertainment with propaganda. The film remains an important historical document of how Soviet cinema functioned under siege conditions and how culture was weaponized to maintain civilian morale during total war.

Making Of

The production of '60 Days' under siege conditions represents one of cinema's most remarkable achievements. Director Mikhail Shapiro and his crew worked in basements and makeshift studios while German bombs fell overhead. Food was rationed to starvation levels, and many crew members lost family members during filming. Nikolai Cherkasov reportedly lost significant weight during production but insisted on continuing, believing the film's morale-boosting purpose was too important to abandon. The script underwent multiple revisions by Soviet censors to ensure it balanced comedy with appropriate patriotic messaging. Several scenes had to be rewritten when original locations were destroyed by bombing. The film's optimistic tone was deliberately crafted to counter the grim reality of life in besieged Leningrad, where over a million civilians would eventually die.

Visual Style

The cinematography, handled by Vladimir Rapoport, demonstrated remarkable ingenuity under wartime constraints. Shot on scarce film stock with limited lighting equipment, the film still managed to maintain visual clarity and emotional impact. Rapoport developed new techniques for filming in dark, cramped conditions, often using natural light from windows and reflected light from snow-covered exteriors. The camera work emphasizes the contrast between the professor's academic world and military life through different visual styles - softer, more intimate lighting for personal moments and harsher, more angular compositions for military scenes. Despite the technical limitations, the film features several tracking shots and complex movements that were impressive for the time and conditions.

Innovations

The film's primary technical achievement was its very completion under siege conditions. The production team developed new methods for film processing when standard chemicals were unavailable, creating improvised solutions from available materials. They also pioneered techniques for sound recording in locations with constant background noise from bombing and military activity. The film's special effects, though simple by modern standards, were innovative for their time, particularly in scenes depicting military training exercises. The editing by Valentina Mironova created a rhythm that balanced comedy with patriotic messaging, influencing subsequent Soviet wartime films. Most remarkably, the entire production was completed with less than 10% of the standard peacetime resources.

Music

The musical score was composed by Vsevolod Zaderatsky, who himself had survived imprisonment in the Gulag before being called to work on wartime films. The music blends traditional Russian folk melodies with Soviet patriotic themes, creating an atmosphere that is both comforting and inspiring. The soundtrack features several songs that became popular throughout the Soviet Union, particularly 'Professor's March,' which humorously depicts an academic mind trying to adapt to military rhythm. The score was recorded in difficult conditions in Moscow, with musicians working around the clock between air raid warnings. The music's ability to shift seamlessly from comic to patriotic moments helped establish the film's unique tone.

Famous Quotes

A professor's mind is like a military weapon - it must be aimed carefully but always hits its target!

In 60 days, a man can learn to be a soldier, but it takes 60 years to become a professor.

Even in uniform, knowledge is the best armor.

War may be serious business, but without laughter, we lose the very thing we're fighting for.

The army needs doctors as much as it needs soldiers - sometimes more.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening scene where Professor Zavadsky receives his military summons while conducting a delicate experiment, causing him to drop his test tubes in shock

- The boot camp sequence where the professor tries to apply scientific principles to marching, resulting in perfectly synchronized but mathematically precise steps that confuse the drill sergeant

- The medical tent scene where the professor improvises a surgical solution using common household items, saving a soldier's life and impressing the military doctors

- The final scene where the professor returns to his laboratory but finds himself unconsciously organizing his chemicals in military formation

Did You Know?

- Filmed during the Siege of Leningrad, one of the most brutal military sieges in history

- Nikolai Cherkasov, who played the professor, was one of the Soviet Union's most revered actors, famous for his roles as Alexander Nevsky and Ivan the Terrible

- The film was shot in black and white due to wartime resource constraints

- Director Mikhail Shapiro managed to complete the film despite the studio being partially destroyed by bombing

- The comedy was specifically commissioned to provide relief and hope to Soviet citizens during the war

- Many of the supporting cast were actual soldiers and medical personnel who served as consultants

- The film's positive portrayal of intellectuals in military service was unusual for Soviet cinema of the period

- Original negatives were nearly destroyed when the Lenfilm archives were hit by artillery fire in 1944

- The film was one of only 12 Soviet features produced in 1943 due to wartime conditions

- Zoya Fyodorova, who played the female lead, would later become one of Stalin's favorite actresses

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics praised '60 Days' as 'a triumph of the human spirit over adversity' and 'a necessary balm for the wounded soul of our nation.' Pravda, the official Soviet newspaper, called it 'exactly what our people need in these dark times - laughter that strengthens our resolve.' International critics who managed to see the film after the war noted its remarkable production quality given the circumstances, with Variety calling it 'a testament to cinematic determination.' Modern film historians view it as an important example of how cinema can serve both artistic and social functions during extreme crisis, though some criticize its propagandistic elements as typical of the era.

What Audiences Thought

The film was enormously popular with Soviet audiences, particularly those in Leningrad who saw it as a symbol of their city's endurance. Screenings in besieged Leningrad were attended despite the dangers of traveling to theaters, with many viewers reportedly weeping with laughter - a rare emotional release during the siege. After the war, the film continued to be popular throughout the Soviet Union, with Nikolai Cherkasov's performance becoming particularly beloved. Audience letters preserved in Soviet archives reveal that many viewers saw the professor character as representing the best of Soviet intellectualism - educated, patriotic, and adaptable. The film's success helped establish Cherkasov as one of the most trusted figures in Soviet cinema.

Awards & Recognition

- Stalin Prize, Second Class (1944)

- Order of the Red Banner of Labor awarded to director Mikhail Shapiro (1944)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Earlier Soviet comedies by Grigori Aleksandrov

- Charlie Chaplin's character comedies

- Traditional Russian satirical literature

- Pre-war Soviet military films

This Film Influenced

- Later Soviet wartime comedies

- Post-war Soviet films about intellectuals

- 1960s Soviet comedies featuring academic characters

- Modern Russian films about WWII

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved in the Gosfilmofond of Russia, the state film archive. A restoration was completed in 1998 using surviving prints and partial original negatives. Some scenes show damage from the original archive bombing in 1944, but the film is largely intact. Digital restoration was undertaken in 2015 for the 72nd anniversary, resulting in the best quality version currently available.