A Page of Madness

Plot

A former sailor takes a janitorial job at a mental asylum where his wife is institutionalized after attempting to drown their child. Through flashbacks and dream sequences, we learn the tragic backstory of how the wife's mental breakdown occurred following the suicide of her sister. The janitor desperately tries to free his wife, plotting to break her out during a chaotic dance performance by the patients. The film blurs reality and hallucination, showing the asylum through distorted perspectives that mirror the characters' fractured psyches. In a surreal climax, the janitor's escape plan fails, and he remains trapped in the asylum with his wife, unable to distinguish between his actual situation and his delusions of freedom.

About the Production

The film was created independently by the Shingekiga (New Drama School) movement, with funding from the cast and crew themselves. Kinugasa sold his personal belongings to help finance the production. The film was shot in secret without studio approval, using borrowed equipment and filming in actual locations including a real mental institution. The production took approximately three months to complete, with innovative techniques achieved through practical effects like mirrors, rapid editing, and experimental camera movements.

Historical Background

The film emerged during Japan's Taishō period (1912-1926), a time of significant cultural modernization and Western influence. This era saw the rise of avant-garde movements in Japanese art and literature, with artists increasingly experimenting with modernist forms. The film reflected growing interest in psychology and mental health treatment in Japan, as well as the influence of European Expressionist cinema. It was created during a period when Japanese cinema was transitioning from traditional theatrical forms toward more realistic and experimental approaches. The film's production coincided with the Great Kantō earthquake of 1923, which had devastated Tokyo and influenced many artists to explore themes of destruction and rebirth.

Why This Film Matters

A Page of Madness is considered a landmark in avant-garde cinema and one of the most innovative Japanese films of the silent era. It demonstrated that Japanese filmmakers could create work on par with European experimental cinema, influencing subsequent generations of Japanese directors. The film's psychological depth and visual innovation predated many similar techniques in Western cinema. It represents a crucial bridge between traditional Japanese theatrical forms and modern cinematic language. The film's rediscovery in the 1970s sparked renewed interest in Japan's lost cinematic heritage and inspired filmmakers worldwide with its bold visual experimentation.

Making Of

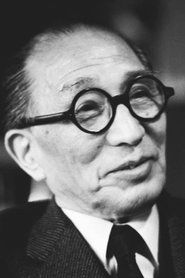

The film was created as an underground project outside the Japanese studio system, with director Teinosuke Kinugasa collaborating with the avant-garde literary group Shinkankakuha (New Sensation School). The production faced numerous challenges including lack of funding, studio disapproval, and technical limitations. The crew developed innovative techniques to achieve surreal effects, such as shooting through textured glass, using rapid montage sequences, and employing unusual camera angles. The asylum scenes were filmed in an actual psychiatric hospital, with some patients participating as extras. The famous dance sequence was choreographed to appear chaotic and disturbing, requiring multiple takes to achieve the desired effect of madness.

Visual Style

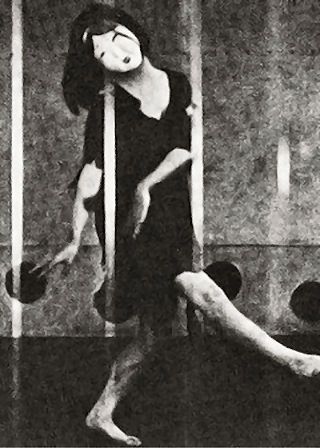

The cinematography by Kohei Sugiyama employed revolutionary techniques including rapid montage sequences, superimpositions, distorted camera angles, and subjective point-of-view shots. The film used mirrors and reflections to create disorienting visual effects that mirrored the characters' mental states. The camera work incorporated handheld movements and unusual framing to convey madness and confusion. The visual style drew heavily from German Expressionism, with dramatic shadows and distorted perspectives. The famous dance sequence used rapid editing and multiple exposures to create a sense of chaos and hysteria.

Innovations

The film pioneered numerous technical innovations including rapid montage sequences, superimposition techniques, and subjective camera work that would not become common for decades. The production achieved surreal effects through practical means including shooting through textured materials, using multiple exposures, and employing unusual camera movements. The film's editing techniques were particularly advanced for the time, with jump cuts and rhythmic editing patterns that created psychological effects. The production also developed new methods for creating distorted visuals without modern optical effects, using mirrors, prisms, and other optical devices.

Music

As a silent film, it was originally accompanied by live musical performance, typically featuring traditional Japanese instruments mixed with Western orchestral elements. The benshi (narrator) would have provided commentary during screenings, though the film's visual nature made it less dependent on narration than typical Japanese films of the era. Modern restorations have been scored by various composers, with most using experimental music to match the film's avant-garde visuals. Some contemporary screenings feature live improvisation by musicians responding to the film's surreal imagery.

Famous Quotes

As a silent film, it contains no spoken dialogue, but its visual poetry creates powerful emotional statements without words

Memorable Scenes

- The chaotic dance sequence where patients perform an erratic ballet, filmed with rapid cuts and distorted angles to convey madness; The opening sequence showing the asylum through a rain-streaked window; The flashback scenes depicting the wife's breakdown through superimposed images; The climactic escape attempt during a storm; The surreal sequence where the janitor sees his wife's face in various objects around the asylum

Did You Know?

- The film was considered lost for over 45 years until Kinugasa discovered a copy in his garden shed in 1971

- It was influenced by German Expressionist cinema and Surrealist art movements

- The original screenplay was written by Yasunari Kawabata, who later won the Nobel Prize in Literature

- The film contains no intertitles, relying purely on visual storytelling

- Only one complete print exists today, held by the National Film Center of Japan

- The dance sequence was inspired by actual therapy sessions at mental institutions

- Kinugasa used multiple exposures and rapid editing techniques decades before they became common

- The film was banned in some regions for its disturbing content and portrayal of mental illness

- The cast largely consisted of avant-garde theater actors from the Shingekiga movement

- The film's title was originally 'Kurutta Ippēji' which translates literally to 'A Crazy Page'

What Critics Said

Upon its initial release, the film received mixed reviews from Japanese critics, with many finding it too experimental and difficult to understand. Mainstream audiences were largely unresponsive, leading to its commercial failure and eventual loss. After its rediscovery in 1971, international critics hailed it as a masterpiece of avant-garde cinema. The film is now regarded by scholars as one of the most important Japanese films of the 1920s, praised for its technical innovation and psychological depth. Modern critics often compare it favorably to European Expressionist works like 'The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari' and 'Un Chien Andalou'.

What Audiences Thought

Contemporary audiences in 1926 largely rejected the film due to its experimental nature and lack of conventional narrative structure. Many viewers found the imagery disturbing and the plot confusing without intertitles. The film's poor reception contributed to its disappearance from theaters and eventual loss. Modern audiences, particularly cinephiles and film students, have embraced the film as a groundbreaking work of art. Contemporary screenings at film festivals and cinematheques typically draw enthusiastic responses, with viewers marveling at the film's visual inventiveness and psychological intensity.

Awards & Recognition

- Kinema Junpo Award for Best Film of the Year (1926)

- Rediscovered as a masterpiece at the 1971 Cannes Film Festival

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920)

- German Expressionist cinema

- Surrealist art movement

- Japanese Noh theater

- Kabuki theater traditions

- Un Chien Andalou (1929) - though released later, shares similar sensibilities

This Film Influenced

- Meshes of the Afternoon (1943)

- Persona (1966)

- The Tenant (1976)

- Tetsuo: The Iron Man (1989)

- Perfect Blue (1997)

- Requiem for a Dream (2000)

- Black Swan (2010)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was considered lost for decades until director Teinosuke Kinugasa discovered a single complete print in his garden shed in 1971. This print is now preserved at the National Film Center of the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo. The film has undergone restoration efforts to preserve its deteriorating elements, though some damage remains visible. It is one of the few surviving examples of Japanese avant-garde cinema from the 1920s, as most films from this period were lost due to natural disasters, war damage, and neglect.