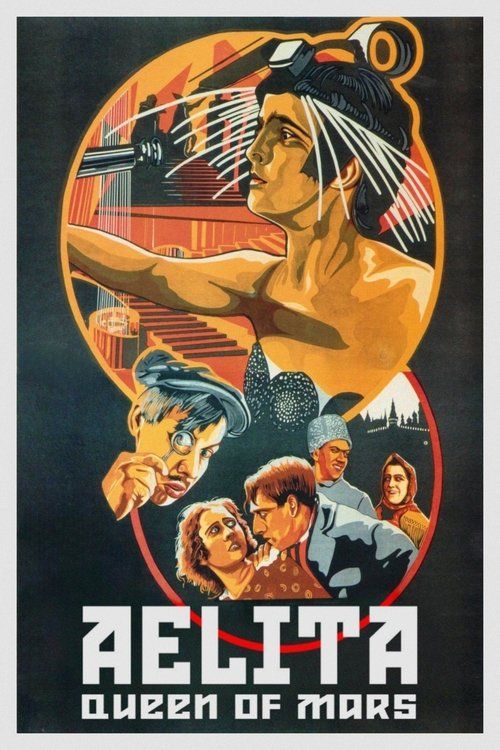

Aelita: Queen of Mars

"The First Soviet Science Fiction Epic - A Journey to the Red Planet!"

Plot

In post-revolutionary Moscow, engineer Los becomes obsessed with Mars after receiving mysterious radio signals, while his wife Natasha grows increasingly distant and involved with her colleague Kravtsov. Los constructs a spaceship and travels to Mars, where he discovers a rigidly stratified society ruled by the elderly Tuskub. Queen Aelita, who has been watching Los through a powerful telescope, has fallen in love with the Earthman and helps him lead a popular uprising against the Martian ruling class. The revolution on Mars parallels the ongoing revolutionary changes on Earth, but when Los discovers that Aelita has betrayed the revolution to maintain her power, he returns to Earth to find that Natasha has left him for Kravtsov. The film concludes with Los realizing that revolutionary change must begin at home, not in distant worlds.

About the Production

The film was shot during the NEP (New Economic Policy) period, allowing for greater artistic experimentation. The Martian sets were designed by prominent constructivist artists including Aleksandra Ekster, Isaac Rabinovich, and Sergei Kozlovsky. The production faced significant technical challenges creating the spaceship effects and Martian landscapes using available 1920s technology. The film's dual narrative structure, showing parallel events on Earth and Mars, was innovative for its time and required complex editing techniques.

Historical Background

Aelita was produced during the NEP (New Economic Policy) period in Soviet Russia (1921-1928), a time of relative cultural liberalization that allowed for artistic experimentation. The film emerged alongside other Soviet avant-garde masterpieces like Eisenstein's Strike and Kuleshov's The Extraordinary Adventures of Mr. West in the Land of the Bolsheviks. This was a crucial period for Soviet cinema, as filmmakers were developing new theories of montage and cinematic language. The film's themes of revolution and class struggle reflected ongoing debates about the direction of Soviet society following the 1917 revolution. The Martian society depicted in the film served as an allegory for contemporary Soviet concerns about bureaucracy, class divisions, and the challenges of building a socialist utopia.

Why This Film Matters

Aelita holds a pivotal place in cinema history as one of the earliest full-length science fiction films and a pioneering work of Soviet cinema. Its innovative use of constructivist design influenced countless later science fiction productions, from Metropolis to modern dystopian films. The film established many tropes that would become standard in science fiction: the alien queen fascinated by Earthlings, the revolutionary overthrow of an oppressive alien society, and the use of space travel as social commentary. Its visual style, particularly the Martian sets and costumes, became iconic representations of futurist design in the 1920s. The film also demonstrated how science fiction could serve as a vehicle for political and social commentary, a tradition that continues in the genre today. Despite being largely forgotten for decades, Aelita has been rediscovered by film scholars and recognized as a crucial link between silent cinema and modern science fiction.

Making Of

Director Yakov Protazanov had recently returned from exile in Berlin when he made this film, bringing Western cinematic techniques to Soviet cinema. The production involved some of the most prominent avant-garde artists of the Soviet avant-garde movement. Constructivist artist Aleksandra Ekster designed the revolutionary Martian costumes and sets, which featured sharp geometric patterns and metallic fabrics. The spaceship scenes were created using miniatures and clever camera work, with the actors suspended by wires. The film's dual narrative structure was revolutionary for its time, requiring complex editing to maintain parallel storylines. The production team built elaborate Martian sets in Moscow studios, using painted backdrops and forced perspective to create the illusion of an alien world. The film's controversial reception led to multiple cuts and revisions before its final release.

Visual Style

The cinematography, handled by Yuri Zhelyabuzhsky, was revolutionary for its time. The film employed innovative techniques to distinguish between Earth and Mars sequences, using different lighting styles and camera angles. Earth scenes were shot in a more conventional style with naturalistic lighting, while Martian sequences featured dramatic, angular lighting and unusual camera placements. The film made extensive use of superimposition and multiple exposure techniques to create the spaceship effects and otherworldly atmosphere. The cinematography emphasized the constructivist design elements through carefully composed shots that highlighted geometric patterns and spatial relationships. The film also featured some of the earliest uses of subjective camera work, particularly in scenes showing Aelita watching Earth through her telescope.

Innovations

Aelita featured several groundbreaking technical achievements for 1924. The film pioneered the use of elaborate miniatures and forced perspective to create its Martian landscapes. The spaceship sequences utilized innovative special effects techniques including multiple exposures and matte paintings. The production team developed new methods for creating the distinctive Martian atmosphere through lighting filters and chemical processes. The film's dual narrative structure required advanced editing techniques to maintain parallel storylines, influencing later Soviet montage theory. The constructivist sets incorporated moving elements and mechanical devices, making them some of the most technically advanced film sets of their time. The film also experimented with color tinting, using different tints to distinguish between Earth (sepia) and Mars (blue-green) scenes.

Music

As a silent film, Aelita originally had no recorded soundtrack but was accompanied by live musical performances in theaters. The recommended score was composed by Vladimir Deshevov, a prominent Soviet composer known for his avant-garde works. The music featured dissonant harmonies and rhythmic complexity to match the film's futuristic themes. Different theaters often used their own arrangements, with some incorporating popular songs of the era while others used more classical selections. Modern restorations have been accompanied by newly composed scores, including works by contemporary composers specializing in silent film music. The original score emphasized the contrast between Earth and Mars through different musical themes and instrumentation.

Famous Quotes

I see you! I see you through my telescope! You are building something... something that will fly to me!

On Earth, there is a revolution. On Mars, there must be a revolution too!

The revolution is not a garden party!

We have watched you for so long, we have learned your ways, your dreams, your revolutions.

To build a new world, we must first destroy the old!

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence showing Aelita watching Earth through her massive telescope, with the revolutionary imagery reflected in her eye

- The construction and launch of the spaceship, featuring innovative special effects and miniature work

- The Martian uprising sequence with thousands of extras in constructivist costumes storming the palace

- The final revelation that Aelita has betrayed the revolution, with her dramatic transformation from revolutionary to tyrant

- The parallel montage showing simultaneous revolutionary activities on Earth and Mars

Did You Know?

- This was one of the first full-length science fiction films ever made, predating Metropolis by three years

- The film was based on a novel by Alexei Tolstoy (distant relative of Leo Tolstoy) published just one year before filming

- Queen Aelita's iconic geometric headdress became a symbol of constructivist fashion in the 1920s

- The Martian language was created specifically for the film, though it was mostly conveyed through gestures and intertitles

- The spaceship design was influenced by early rocketry concepts of Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, the father of Soviet rocket science

- Despite being a Soviet film, it was briefly banned for its 'bourgeois' elements and escapist themes

- The film was one of the first Soviet productions to be exported internationally, showing in Europe and the United States

- Yuliya Solntseva, who played Aelita, later became a prominent film director herself

- The film's Martian society was an allegory for contemporary Soviet class struggles

- Original prints were tinted in various colors to distinguish between Earth (sepia) and Mars (blue-green) scenes

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics were divided about Aelita. Some praised its technical achievements and artistic innovation, while others criticized its 'bourgeois' tendencies and escapist themes. Pravda initially condemned the film for distracting workers from building socialism with its fantastic elements. However, Western critics were more enthusiastic, with Variety praising its visual imagination and technical prowess. Modern critics have reevaluated the film much more positively, recognizing its historical importance and artistic achievements. The film is now considered a masterpiece of early science fiction and a key work of Soviet avant-garde cinema. Film historians particularly praise its innovative set design, dual narrative structure, and sophisticated use of visual metaphor.

What Audiences Thought

Initial Soviet audience reception was mixed, with many viewers confused by the film's complex dual narrative and allegorical elements. However, the film was popular enough to achieve international distribution, unusual for Soviet productions of the time. Audiences were particularly impressed by the spectacular Martian sets and the novelty of seeing a full-length science fiction story. The romantic subplot between Los and Aelita resonated with viewers, despite the film's revolutionary themes. In later years, as the film gained cult status among science fiction enthusiasts, audience appreciation grew significantly. Modern audiences at revival screenings and film festivals have responded enthusiastically to the film's visual creativity and historical significance.

Awards & Recognition

- No major awards were given to Soviet films in 1924, as the Soviet film award system was not yet established

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Alexei Tolstoy's novel 'Aelita' (1923)

- Early Soviet revolutionary cinema

- Constructivist art movement

- Fritz Lang's German expressionist films

- Konstantin Tsiolkovsky's rocketry theories

- Soviet montage theory

- Georges Méliès's early fantasy films

This Film Influenced

- Metropolis (1927)

- The Woman in the Moon (1929)

- Things to Come (1936)

- Flash Gordon serials

- Solaris (1972)

- Stalker (1979)

- Blade Runner (1982)

- The Fifth Element (1997)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved and restored by the Gosfilmofond of Russia. Several versions exist, including the original 1924 cut and later re-edited versions. The most complete restoration was completed in the 1990s, incorporating surviving footage from various archives. Some scenes remain lost or incomplete, particularly from the Earth sequences. The restored version features reconstructed intertitles based on original scripts and production documents. The film has been released on DVD and Blu-ray by several specialty distributors, including Criterion and Kino Lorber.