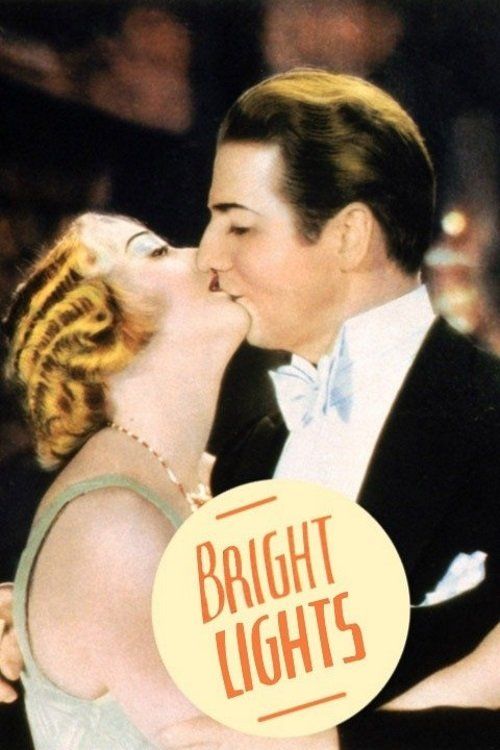

Bright Lights

"From queen of a thousand miners to belle of New York's smart set!"

Plot

Louanne, a celebrated Broadway star, is on the verge of retiring to marry the wealthy and aristocratic Emerson Fairchild. To maintain her new social standing, she provides the press with a sanitized, fictionalized account of her upbringing as a refined lady. However, the film uses flashbacks to reveal her true, gritty past as a hula dancer in sleazy African dives and a carnival performer alongside her loyal partner, Wally Dean, who is secretly in love with her. The situation turns perilous when Miguel Parada, a Portuguese smuggler from her past who bears a scar from their last violent encounter, appears in the audience seeking revenge. During a backstage confrontation, a struggle ensues and Parada is killed, forcing Louanne and Wally to navigate a murder investigation that threatens to expose her lies and destroy her future.

About the Production

The film was originally conceived as a 'roadshow' attraction and was one of the many lavish musicals produced during the early sound era. It was filmed entirely in two-strip Technicolor, a process that was expensive and technically demanding at the time. Director Michael Curtiz reportedly ordered the painting of live birds (parrots and canaries) because their natural colors did not appear 'deep' enough under the intense sun-arc lights required for the Technicolor cameras. Production began in late 1929 and was completed in early 1930, but the film's release was delayed and edited due to a sudden decline in public interest in musicals.

Historical Background

1930 was a pivotal year in Hollywood as the industry fully embraced 'talkies' while grappling with the onset of the Great Depression. 'Bright Lights' was produced during the 'Technicolor Fever' of 1929-1930, when studios believed color and sound would permanently revolutionize cinema. However, the high cost of color film and the economic downturn soon led studios to abandon Technicolor for several years. The film also exists in the 'Pre-Code' era, a brief window before the strict enforcement of the Motion Picture Production Code in 1934, allowing for the inclusion of murder, attempted rape, and suggestive costuming that would later be censored.

Why This Film Matters

The film is a significant artifact of the 'backstage musical' genre that would later be perfected by Busby Berkeley. It serves as a bridge between the silent era's melodramatic storytelling and the sound era's obsession with spectacle and music. It also highlights the career of Dorothy Mackaill, a major silent star who successfully transitioned to sound but whose career faded shortly after the Pre-Code era ended. The film's 'African' sequences are also noted by modern historians for their period-typical, albeit problematic, depictions of exoticism and race.

Making Of

The production of 'Bright Lights' was a transitionary effort for Michael Curtiz, who was then a rising 'journeyman' director at Warner Bros. Known for his efficiency, Curtiz managed a production that blended high-budget musical numbers with gritty, backstage melodrama. The use of Technicolor required massive amounts of light, making the sets incredibly hot and difficult for the actors. To achieve the desired 'exotic' look for the African flashbacks, the crew had to meticulously style the sets to contrast with the sleek, modern Broadway environments. The film also faced challenges with the changing tastes of the public; by the time it was ready for wide release, the 'musical craze' of 1929 had cooled, leading the studio to cut several musical numbers to focus more on the crime and drama elements.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Lee Garmes and Charles Edgar Schoenbaum was highly ambitious, utilizing the two-strip Technicolor process to create a vivid, if somewhat unnatural, color palette. The film uses 'sun-arcs' to illuminate the sets, creating deep shadows and high contrast. Notable visual techniques include the use of silhouettes for suggestive scenes and the 'Gilligan Cut' style of editing during Louanne's fictionalized retelling of her past, where the visuals humorously contradict her words.

Innovations

The primary technical achievement was the use of full-length two-strip Technicolor in a feature-length 'talkie.' The production also utilized complex 'playback' technology for musical numbers, allowing actors to perform to pre-recorded tracks, which was a relatively new technique in 1930.

Music

The soundtrack features several original songs by Ned Washington, Ray Perkins, and others. Notable tracks include 'Nobody Cares If I'm Blue' (sung by Frank Fay), 'I'm Crazy for Cannibal Love' (a controversial 'exotic' number sung by Mackaill), 'Song of the Congo,' and 'Every Little Girl He Sees.' The music was recorded using the Vitaphone sound-on-disc system.

Famous Quotes

Louanne: 'I don't believe in misrepresenting myself to the press for the sake of publicity!'

Wally Dean: 'Why don't you marry that guy and forget him?'

Miguel Parada: 'No matter where you hide it, I'll find it!' (referring to her past)

Reporter: 'When I heard the shot, I fell right off his lap. Wanna see the bruise?'

Memorable Scenes

- The opening scene where Louanne is introduced lounging in a negligee with a parrot, establishing her 'star' persona.

- The 'Cannibal Love' musical number, featuring elaborate costumes and the controversial 'black body stocking' backup dancers.

- The flashback to the African dive where Louanne performs a 'fiery' hula and narrowly escapes an assault by Miguel Parada.

- The climactic backstage struggle where the villainous Parada is shot, followed by the frantic attempt to frame it as a suicide to save Louanne's reputation.

Did You Know?

- This film marks the uncredited screen debut of legendary character actor John Carradine, who appears as a photographer during the press conference scene.

- The film was originally titled 'Adventures in Africa' during production and was later retitled for its Broadway-themed marketing.

- Though filmed entirely in Technicolor, the film is primarily known today through a black-and-white print; only a three-minute fragment of the original color footage is known to survive in the Library of Congress.

- Dorothy Mackaill, a former Ziegfeld Follies girl, performed her own singing and dancing, including a provocative 'hula' number.

- The project underwent significant casting changes; originally, Lloyd Bacon was set to direct with Loretta Young in the lead role.

- A $25,000 copyright infringement lawsuit was filed by writer Margaret Drennen, who claimed the story was based on her original work.

- The film features a scene where Dorothy Mackaill undresses in silhouette, a classic example of 'Pre-Code' risqué content.

- Frank Fay, the male lead, was at the time a major vaudeville star and the husband of Barbara Stanwyck.

- The film was pulled from wide release in late 1930 and re-edited for a 1931 re-release because audiences were becoming 'tired' of musicals.

What Critics Said

At the time of its release, 'Bright Lights' received mixed reviews. The New York Times described it as a 'backstage yarn' with high-caliber cast performances but a familiar plot. Modern critics view it as a 'fascinating pre-code oddity,' praising Mackaill's vivacious performance while noting that the film struggles to balance its wildly different tones—ranging from lighthearted musical comedy to dark crime drama.

What Audiences Thought

Initial audience reception was lukewarm, largely due to 'musical fatigue' that hit the American public in 1930. While the 'roadshow' premiere in Los Angeles was a success, the general release was less impactful, leading to the film being re-edited. Today, it is a cult favorite among Pre-Code cinema enthusiasts who appreciate its bizarre plot shifts and vintage production values.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The Broadway Melody (1929)

- On With the Show! (1929)

This Film Influenced

- 42nd Street (1933)

- Singin' in the Rain (1952) - specifically the 'fictionalized biography' trope

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is considered partially lost in its original form. While the complete film survives in a black-and-white 1931 reduction print, the original 1930 Technicolor version is lost, save for a three-minute color fragment discovered in the Library of Congress.