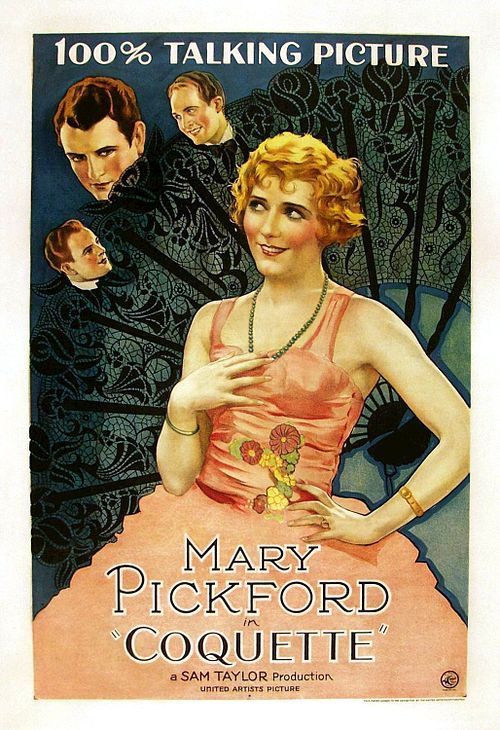

Coquette

"Mary Pickford's First Talking Picture!"

Plot

Norma Besant, a vivacious Southern belle and daughter of a respected doctor, enjoys her status as the most sought-after young woman in town. Despite being engaged to the wealthy and socially acceptable Stanley Wentworth, she finds herself drawn to Michael Jeffrey, a handsome but poor cotton mill worker. Their secret romance blossoms through clandestine meetings, but when her father discovers their relationship, he vehemently forbids it due to class differences. Tragedy strikes when Dr. Besant confronts Michael and shoots him in a fit of rage, leading to a courtroom drama where Norma must choose between protecting her father and revealing the truth about her relationship with Michael. The film culminates in a devastating emotional reckoning that exposes the rigid social hierarchies and destructive consequences of prejudice in the American South.

About the Production

This was Mary Pickford's first sound film, a risky transition for the silent film superstar who had built her career playing innocent young girls. The production faced significant technical challenges as early sound recording equipment was cumbersome and limited camera movement. Pickford, who was also a producer through her Pickford Corporation, insisted on extensive rehearsals before filming to ensure perfect dialogue delivery. The film was shot using the Movietone sound-on-film system rather than Vitaphone, which was still in development. The Southern setting was recreated on studio backlots and locations in California, as location shooting with sound equipment was nearly impossible in 1929.

Historical Background

The year 1929 marked a pivotal moment in American cinema history as the industry was in the midst of the rapid transition from silent to sound films. The Wall Street Crash of October 1929 occurred just months after the film's release, dramatically altering the entertainment landscape and audience spending habits. This period also saw significant social changes, with the flapper era challenging traditional Victorian values and women increasingly asserting their independence. The film's themes of class conflict and romantic rebellion reflected the growing tensions in American society between old money and working-class aspirations. The South depicted in the film was still grappling with the legacy of the Civil War and Reconstruction, while modernization was rapidly changing traditional ways of life. The Jazz Age was in full swing, bringing new attitudes toward sexuality and social relationships that were reflected in the film's relatively frank treatment of romantic desire.

Why This Film Matters

'Coquette' holds immense cultural significance as a document of Hollywood's transition to sound and as a showcase of Mary Pickford's evolution as an actress. The film demonstrated that silent film stars could successfully make the leap to talkies, though Pickford's career would ultimately never regain the heights of her silent era success. It represents one of the earliest examples of a major star deliberately breaking away from their established screen persona, a practice that would become increasingly common in later decades. The film's treatment of class divisions and romantic rebellion anticipated many of the social dramas that would become popular in the 1930s. Pickford's Academy Award win for this performance was controversial at the time and has remained so among film historians, as many felt her performance was not her strongest work. The film also serves as an important example of early sound techniques and the limitations directors faced during this transitional period.

Making Of

The making of 'Coquette' represented a crucial turning point in Hollywood's transition to sound. Mary Pickford, one of the most powerful figures in silent cinema, approached this project with both excitement and trepidation. The production required extensive soundproofing of studio sets, with cameras housed in bulky booths to prevent motor noise from being picked up by the microphones. Pickford, who had never spoken on screen before, took voice lessons for months and demanded multiple takes to perfect her delivery. The famous scene where she cuts her hair was actually done on camera, with Pickford making the decision to cut her signature curls as part of her character's transformation. Director Sam Taylor, who had worked with Pickford on several silent films, struggled with the technical limitations of early sound recording but managed to create some surprisingly intimate moments despite the equipment constraints. The courtroom scenes were particularly challenging to film, as the actors had to remain relatively still to stay within microphone range while still delivering emotionally charged performances.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Charles Rosher and Karl Struss represents a fascinating hybrid of silent and early sound techniques. The camera work is more static than in late silent films due to the technical limitations of early sound recording, but the visual composition remains sophisticated. The filmmakers used lighting to create dramatic shadows that enhance the film's emotional intensity, particularly in the romantic scenes between Pickford and Brown. The Southern setting is rendered through carefully composed shots that evoke a sense of place despite being filmed on California backlots. The courtroom scenes use deep focus to capture the entire dramatic space, a technique that would become more common in the 1930s. The film's visual style successfully bridges the gap between the expressive cinematography of the late silent era and the more naturalistic approach that would dominate sound cinema.

Innovations

The film's primary technical achievement was its successful implementation of early sound recording technology. The production used the Movietone sound-on-film system, which offered better synchronization than the competing Vitaphone process. The filmmakers developed innovative solutions to common sound problems of the era, including the use of hidden microphones and creative camera placement to maintain visual interest while staying within recording range. The film also demonstrated early experiments with post-production dubbing, as some scenes were re-recorded to improve audio quality. The successful integration of music, dialogue, and sound effects in a dramatic context was considered groundbreaking for its time. The film's technical crew also developed new methods for reducing echo in large sets, a problem that plagued many early sound productions.

Music

The film's musical score was composed by Cecil Copping and performed by a full orchestra recorded using the Movietone system. As was common in early talkies, the music served both as underscoring and as scene-setting diegetic music. The score incorporates Southern folk melodies and popular songs of the era to establish the film's regional setting. The recording quality is typical of 1929, with noticeable hiss and limited frequency range, but the music remains clear and expressive. The film also uses source music strategically, particularly in scenes depicting social gatherings, to enhance the period atmosphere. The soundtrack represents an important example of how Hollywood adapted traditional film scoring techniques to the new demands of synchronized sound.

Famous Quotes

I'm not a child anymore, Father. I'm a woman who knows her own mind.

Love doesn't ask about bank accounts or family trees.

In the South, some things are more important than the truth.

You can't build happiness on someone else's misery.

Memorable Scenes

- The scene where Norma defiantly cuts her signature curls, symbolizing her transformation from girl to woman and her rejection of societal expectations.

- The clandestine meeting between Norma and Michael by the river, where their forbidden romance blossoms against the backdrop of Southern moonlight.

- The explosive confrontation between Dr. Besant and Michael, leading to the tragic shooting that changes everyone's lives forever.

- The climactic courtroom scene where Norma must choose between protecting her father and revealing the truth about her relationship.

Did You Know?

- Mary Pickford won the Academy Award for Best Actress for this performance, making her one of the few actresses to win for a role that was initially panned by critics.

- This film marked a dramatic departure for Pickford, who had built her career playing innocent young girls and was known as 'America's Sweetheart.' Here she played a sophisticated, sexually aware woman.

- The film was based on a 1927 Broadway play by Martin Flavin, which starred Helen Hayes in the lead role.

- Johnny Mack Brown, a former All-American football player, was cast against type as the romantic lead. He would later become famous as a Western star.

- Pickford famously cut her famous curls into a bob for this role, which was considered shocking to her fans and symbolized her transition from child star to adult actress.

- The film's success helped establish United Artists as a major player in the sound era, as Pickford was one of the studio's co-founders.

- Despite its box office success, Pickford considered this film one of her lesser works and rarely spoke about it in later years.

- The original Broadway production ran for 173 performances and was considered quite risqué for its time.

- Pickford's husband Douglas Fairbanks was reportedly uncomfortable with her kissing scenes in the film.

- The film's sound recording was so primitive that the orchestra had to be recorded separately and then synchronized with the actors' performances.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception was mixed, with many reviewers praising Pickford's courage in taking on such a different role while questioning whether she was suited for it. Variety noted that 'Pickford proves she can talk, but whether she can act in talking pictures remains to be seen.' The New York Times was more positive, calling it 'a brave and successful experiment' for the star. Modern critics have reevaluated the film more favorably, recognizing its historical importance and noting that Pickford's performance was actually quite nuanced for the early sound era. The film is now appreciated as a fascinating artifact of its time, showcasing the challenges and possibilities of early sound cinema. Film historians particularly value the courtroom scenes as examples of how directors adapted theatrical techniques for the new medium.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences flocked to see 'Coquette' out of curiosity to hear their beloved Mary Pickford speak for the first time. The film was a box office success, grossing over $1.4 million domestically, a substantial sum for 1929. However, many of Pickford's longtime fans were reportedly shocked by her mature performance and the film's relatively serious tone. The scene where she cuts her famous curls caused particular consternation among her traditional fan base. Despite these reactions, the film's commercial success proved that audiences would accept their silent idols in talking pictures, provided the material was compelling. The film's themes of romantic rebellion and class conflict resonated with young audiences during this period of social change, even if older viewers found the story somewhat scandalous.

Awards & Recognition

- Academy Award for Best Actress (Mary Pickford)

- Photoplay Medal of Honor

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The Broadway play 'Coquette' by Martin Flavin

- Southern Gothic literature

- Victorian melodrama

- Early social problem films

This Film Influenced

- Other early sound dramas

- Films about class conflict in America

- Southern-themed melodramas of the 1930s

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved in the Library of Congress and has been restored by the UCLA Film and Television Archive. A complete 35mm print exists in excellent condition, and the film has been released on DVD and Blu-ray with restored audio. The preservation work has significantly improved the sound quality from the original release, making the dialogue much clearer than in earlier home video versions.