Different from the Others

Plot

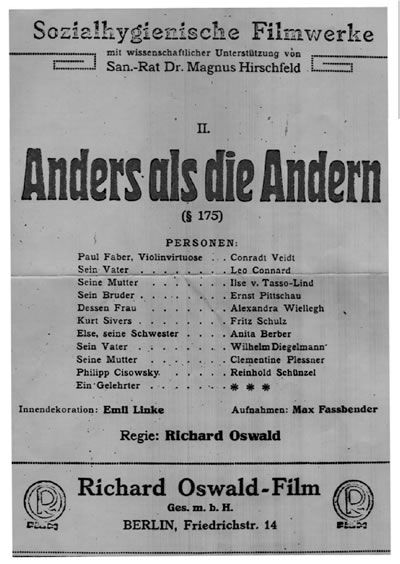

Paul Körner, a celebrated concert violinist, falls deeply in love with his talented young student Kurt Sivers. Their romantic relationship is discovered by Franz Bollek, a former lover of Paul who becomes a malicious blackmailer, threatening to expose Paul under Germany's Paragraph 175 law criminalizing homosexuality. Despite attempts to resist the blackmail and seek help from a sympathetic doctor, Paul is eventually arrested, tried, and convicted, leading to complete social ostracization and professional ruin. The film culminates in Paul's suicide, followed by a direct address to the audience by Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld (playing himself), who passionately argues for the abolition of Paragraph 175 and greater scientific understanding of homosexuality as a natural variation of human sexuality.

About the Production

The film was a collaborative effort between director Richard Oswald and sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld, who co-wrote the screenplay and appeared in the film. It was produced as part of Hirschfeld's educational efforts to combat prejudice against homosexuals. The production faced censorship challenges from the start, requiring multiple cuts to secure approval from German film censors. The film was shot during the relatively liberal period of the Weimar Republic, when such subject matter could still be addressed, albeit with significant restrictions.

Historical Background

The film emerged during the Weimar Republic's early years, a period of unprecedented cultural and social liberalism in Germany following World War I. This era saw the flourishing of LGBTQ communities, particularly in Berlin, which had become known as a haven for sexual minorities. Paragraph 175, the law criminalizing male homosexuality, had been in place since 1871, but its enforcement varied. Magnus Hirschfeld had been campaigning for its repeal since the 1890s, founding the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee in 1897. The film was produced amid growing scientific understanding of sexuality, though still facing widespread social prejudice. Its release came just as conservative and nationalist forces were beginning to organize against the perceived decadence of Weimar culture, foreshadowing the Nazi crackdown that would come a decade later.

Why This Film Matters

Different from the Others represents a landmark in LGBTQ cinema history as the first feature-length film to present homosexuality in a sympathetic, non-judgmental manner. It broke ground by portraying gay characters as complex, sympathetic human beings rather than caricatures or villains. The film's direct political message—advocating for the repeal of anti-homosexuality laws—was unprecedented in cinema. Its influence extends far beyond its initial release, as surviving fragments have become crucial historical documents for understanding early LGBTQ representation and activism. The film demonstrated cinema's potential as a tool for social change and education, particularly regarding taboo subjects. Its destruction by the Nazis and partial recovery decades later has made it a powerful symbol of both the fragility of LGBTQ cultural heritage and the resilience of queer history.

Making Of

The collaboration between Richard Oswald and Magnus Hirschfeld was groundbreaking for its time. Oswald, already known for his 'enlightenment films' (Aufklärungsfilme) about social issues, partnered with Hirschfeld to create what was essentially a propaganda film for gay rights. The production faced immediate censorship challenges, with German authorities demanding cuts to any scenes that might 'corrupt public morals.' The filmmakers strategically included Hirschfeld's scientific explanations and direct-to-camera address to frame the film as educational rather than purely entertainment. Conrad Veidt's casting was significant, as he was already a rising star in German cinema, lending credibility to the controversial subject matter. The film's production coincided with the brief flowering of LGBTQ culture in Weimar Berlin, making it both a product of and contributor to this progressive moment in German history.

Visual Style

The surviving fragments reveal competent but conventional cinematography typical of German films of the late 1910s. The visual style employs standard techniques of the era including intertitles, medium shots, and occasional close-ups to convey emotion. The film uses lighting to create mood, particularly in scenes depicting Paul's isolation and despair. The camera work is relatively static, as was common in early cinema, but shows some sophistication in its composition and use of space. The visual presentation of Paul's musical performances suggests attempts to convey artistic passion through gesture and expression. The cinematography, while not technically revolutionary, effectively serves the film's dramatic and educational purposes.

Innovations

While not technically innovative in terms of cinematic techniques, the film's achievement lies in its pioneering approach to controversial subject matter. The integration of educational content within a dramatic narrative was relatively sophisticated for its time. The film's use of a real scientist (Hirschfeld) playing himself to deliver direct addresses to the audience was an innovative approach to blending documentary and fiction. The surviving footage shows competent use of cross-cutting and narrative structure to build emotional engagement. The film's technical aspects served its primary purpose of advocacy and education, using established cinematic techniques to make its controversial content more accessible to audiences.

Music

As a silent film, Different from the Others would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The specific musical arrangements used have not been documented, but they likely included classical pieces appropriate to the protagonist's career as a violinist. Modern restorations and screenings typically feature newly composed scores or period-appropriate classical music. The film's central character being a musician suggests that music was meant to play an important thematic role, though the original musical choices are unknown. Contemporary screenings often use composers like Edvard Grieg or other romantic era composers whose work would have been familiar to 1919 audiences.

Famous Quotes

We must abolish the infamous paragraph 175, which has brought so much unhappiness to so many people.

Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld (direct address to audience)

Love is not a crime.

Paul Körner

Science has proven that homosexuality is a natural variation of human sexuality.

Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld

The law must protect, not persecute.

Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld

We are different from others, but not less than others.

Paul Körner

Memorable Scenes

- The opening scene where Paul Körner performs his violin concert, establishing his artistic brilliance and social standing before his secret is revealed

- The tense blackmail scene where Franz Bollek threatens to expose Paul under Paragraph 175, capturing the fear and vulnerability of gay men in this era

- The courtroom sequence where Paul is tried and convicted, showing the legal system's persecution of homosexuality

- Paul's suicide scene, a powerful moment depicting the tragic consequences of social intolerance

- The final scene where Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld breaks the fourth wall to directly address the audience about sexual science and legal reform

- The tender scenes between Paul and Kurt showing their genuine love and affection, revolutionary for their time

Did You Know?

- This is considered the first film in cinema history to openly and sympathetically portray homosexual characters and relationships

- The film was co-written by Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld, a pioneering sexologist who founded the world's first gay rights organization

- Conrad Veidt, who played the lead role, later became famous for starring in 'Casablanca' (1942) as Major Strasser

- The film was produced with the specific goal of campaigning against Paragraph 175, the German law criminalizing homosexuality

- Most copies of the film were destroyed by the Nazis in the 1930s, with only fragments surviving in archives

- The surviving footage was discovered in the 1970s in the Soviet Union, where it had been archived as 'degenerate art'

- Anita Berber, who plays the sister, was a notorious dancer and actress of the Weimar era known for her scandalous lifestyle

- The film was banned in many cities and countries upon release, including Austria and parts of Germany

- Hirschfeld's Institute for Sexual Science, which co-produced the film, was destroyed by Nazi students in 1933

- The film's title 'Different from the Others' was carefully chosen to suggest natural variation rather than deviance

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception was mixed but largely positive among progressive circles. Liberal newspapers praised the film's courage and educational value, with some reviewers noting its artistic merits despite its didactic purpose. However, conservative press condemned it as immoral and dangerous propaganda. Modern critics and film historians have recognized the film as a groundbreaking work of queer cinema, praising its boldness and historical importance despite the limitations of the surviving footage. The film is now studied as a crucial document of early LGBTQ representation and Weimar-era sexual politics, with scholars noting its sophisticated approach to narrative and its integration of educational content within a dramatic framework.

What Audiences Thought

Initial audience reception was divided along political and social lines. Progressive audiences, particularly in Berlin's more liberal districts, reportedly responded positively to the film's sympathetic portrayal of homosexuality. Many LGBTQ individuals found validation in seeing their experiences represented on screen for the first time. However, conservative audiences often reacted with hostility, and the film faced protests in some cities. The film's limited release due to censorship restrictions meant it never reached a mass audience. In the decades since its rediscovery, it has found new audiences among LGBTQ communities, film scholars, and those interested in queer history, who view it as an important ancestor of modern queer cinema.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Magnus Hirschfeld's scientific writings on sexuality

- German enlightenment film tradition

- Weimar-era sexual liberation movements

- Early 20th century sexology research

- German Expressionist cinema (in visual style)

This Film Influenced

- Mädchen in Uniform (1931)

- Victim (1961)

- The Children's Hour (1961)

- The Boys in the Band (1970)

- Paris Is Burning (1990)

- Philadelphia (1993)

- Brokeback Mountain (2005)

- The Danish Girl (2015)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is partially preserved with approximately 40 minutes of footage surviving from the original 50-minute runtime. Most copies were systematically destroyed by the Nazis in the 1930s as part of their campaign against 'degenerate art.' The surviving fragments were discovered in the 1970s in the Gosfilmofond archive in the Soviet Union. The film has been partially restored by film archives including the UCLA Film and Television Archive and the Museum of Modern Art. Some scenes exist only in transcript form from original censorship documents. The restored version includes intertitles reconstructed from these documents and other historical sources.