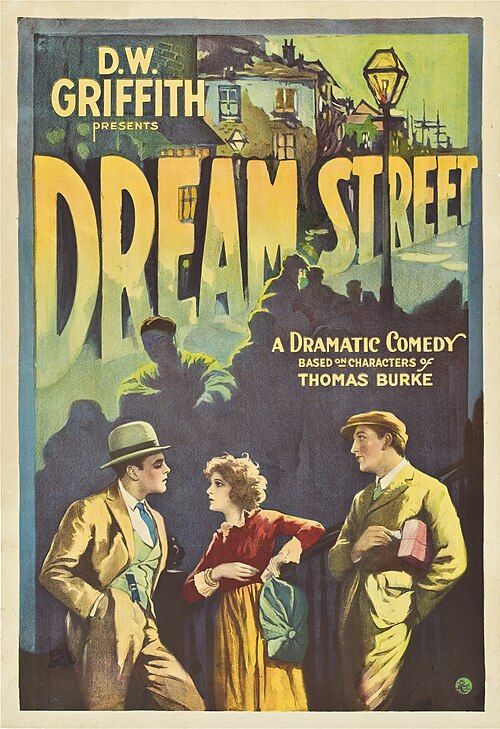

Dream Street

"A Story of the London Underworld"

Plot

Set in the impoverished London district of Limehouse, 'Dream Street' follows Gypsy Fair, a dance-hall girl who becomes the object of affection for three very different men. The suitors include a wealthy but kind-hearted American named William Jenkins, a brutish local prizefighter named Billy, and a gentle Chinese shopkeeper named 'The Yellow Man.' As the story unfolds, Gypsy must navigate her feelings while dealing with the harsh realities of her working-class existence. The narrative explores themes of love, sacrifice, and redemption as Gypsy ultimately makes a choice that will determine her fate. The film's climax involves a dramatic confrontation that tests the true nature of each suitor's love and character.

About the Production

Griffith built an elaborate London street set costing over $100,000, complete with authentic British props and architecture. The production faced challenges with Carol Dempster's performance, requiring extensive reshoots. Griffith experimented with new lighting techniques to create the moody atmosphere of London's Limehouse district. The film was one of Griffith's first productions after forming his own company following his departure from Famous Players-Lasky.

Historical Background

Released in 1921, 'Dream Street' emerged during a transitional period in American cinema and society. The film industry was consolidating with the formation of United Artists the previous year, giving directors like Griffith unprecedented creative control. Post-World War I America was experiencing the Roaring Twenties, with changing social mores reflected in cinema's more daring content. The film's depiction of London's Limehouse district tapped into contemporary American fascination with exotic urban settings and the underworld. Griffith, still riding the controversial legacy of 'The Birth of a Nation' (1915), was attempting to reclaim his artistic reputation with more socially conscious material. The early 1920s also saw cinema transitioning from short films to feature-length productions, with 'Dream Street' representing the industry's growing technical and narrative ambitions.

Why This Film Matters

'Dream Street' represents an important but often overlooked chapter in D.W. Griffith's filmography and early 1920s cinema. The film demonstrated Griffith's continued technical innovation, particularly in lighting and set design, influencing subsequent urban dramas. Its exploration of class dynamics and urban poverty contributed to the growing trend of socially conscious films in the early 1920s. The movie also reflects period attitudes toward race and internationalism, particularly in its portrayal of Chinese characters, which provides valuable insight into early Hollywood's representation of Asian culture. While not as historically significant as Griffith's earlier masterpieces, the film serves as an important example of post-war American cinema's evolution toward more complex narratives and sophisticated production values. Its experimentation with synchronized sound presaged the industry's eventual transition to talkies.

Making Of

The production of 'Dream Street' marked a significant transition in D.W. Griffith's career as he established his independence from major studios. Griffith invested heavily in creating an authentic London atmosphere, importing British cobblestones and hiring European consultants for set design. The relationship between Griffith and Carol Dempster became a source of tension on set, with Griffith giving her preferential treatment while other cast members felt neglected. The film's extensive reshoots and budget overruns strained Griffith's new production company. Notably, Griffith experimented with early sound technology, recording a synchronized musical score and sound effects that were groundbreaking for 1921, though this version is now considered lost. The production also faced censorship challenges due to its depiction of London's underworld and interracial romance elements.

Visual Style

The cinematography in 'Dream Street' showcases D.W. Griffith's continued innovation in visual storytelling. Hendrik Sartov served as cinematographer, employing sophisticated lighting techniques to create the moody atmosphere of London's Limehouse district. The film features extensive use of low-key lighting and shadows to enhance the dramatic tension, particularly in night scenes. Griffith experimented with camera movement and unusual angles, including some early examples of tracking shots that followed characters through the elaborate street sets. The production utilized multiple cameras for certain sequences, allowing for more dynamic editing. The film also featured carefully composed deep focus shots, maintaining clarity in both foreground and background elements. Visual motifs, particularly recurring images of street lamps and windows, create symbolic depth throughout the narrative.

Innovations

'Dream Street' featured several technical innovations for its time, most notably its early use of synchronized sound. The Phonofilm system used for the sound version represented a significant step toward the talkie revolution that would transform cinema in the late 1920s. The film's elaborate London street set was a marvel of production design, featuring working gas lamps, cobblestone streets, and detailed facades that could be reconfigured for different scenes. Griffith's team developed new lighting techniques to create authentic London atmosphere, including specialized filters and lighting rigs for night scenes. The production also experimented with multiple camera setups and sophisticated editing techniques that enhanced narrative flow. The film's use of color tinting for different times of day and moods, while not revolutionary, demonstrated the growing sophistication of film presentation techniques in the early 1920s.

Music

The original release of 'Dream Street' featured a synchronized musical score composed by Louis F. Gottschalk, representing one of the earliest examples of feature films with recorded sound. The score utilized the Phonofilm process, which allowed for synchronization of music and sound effects with the projected image. The soundtrack included popular songs of the era, original compositions, and atmospheric sound effects like street noises and crowd sounds. For the dance-hall sequences, contemporary jazz and ragtime music was incorporated to enhance the period authenticity. The musical accompaniment emphasized the film's emotional beats, with romantic themes for love scenes and dramatic motifs for confrontations. Unfortunately, the sound version of the film is believed lost, with only silent versions surviving. Modern screenings typically feature newly composed scores or period-appropriate music.

Famous Quotes

"In this world of shadows, love is the only light that never fades." - Opening intertitle

"The streets may be dirty, but some hearts remain clean." - Gypsy Fair

"Love knows no borders, no class, no color - only truth." - Intertitle

"In Limehouse, every dream has its price." - Narrator intertitle

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence establishing the Limehouse district with atmospheric fog and gas-lit streets

- The dance-hall competition where the three suitors attempt to win Gypsy's affection

- The dramatic rooftop confrontation between the American and the prizefighter

- The tender scene between Gypsy and the Chinese shopkeeper in his tea shop

- The final chase through the London streets at dawn

Did You Know?

- This was D.W. Griffith's first film for United Artists, which he co-founded with Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford, and Douglas Fairbanks

- Carol Dempster, Griffith's protégé and rumored romantic partner, received top billing despite being relatively unknown

- The film featured an early use of color tinting, with amber tones for day scenes and blue-green for night sequences

- Original prints included a synchronized musical score and sound effects using the Phonofilm system, though most surviving versions are silent

- The Chinese character 'The Yellow Man' was played by white actor Ralph Graves in yellowface, common for the period but controversial today

- Griffith reportedly spent more time on the film's elaborate sets than on directing the actors

- The dance-hall sequences featured authentic period choreography researched by Griffith's team

- A fire at Griffith's studio destroyed some of the original footage, requiring reshoots

- The film was released in both silent and sound versions to accommodate different theaters

- Contemporary critics noted the film's technical achievements but criticized its melodramatic plot

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics gave 'Dream Street' mixed reviews, praising Griffith's technical mastery and atmospheric direction while criticizing the film's melodramatic plot and Dempster's performance. The New York Times noted the film's 'impressive sets and lighting effects' but found the story 'somewhat conventional.' Variety appreciated Griffith's ambition but felt the film lacked the emotional impact of his earlier works. Modern critics have reassessed the film more favorably, recognizing its technical achievements and historical importance while acknowledging its problematic elements. Film historians view it as an important transitional work in Griffith's career, demonstrating his adaptation to changing cinematic tastes. The surviving version's incomplete nature has made definitive critical assessment challenging, though scholars generally agree it represents an underrated example of early 1920s filmmaking.

What Audiences Thought

Audience response to 'Dream Street' was moderate, with the film achieving reasonable box office returns but failing to match the success of Griffith's previous epics. Contemporary theater reports indicated that audiences responded well to the film's visual spectacle and dramatic moments, though some found the pacing slow compared to more action-oriented films of the era. The dance-hall sequences were particularly popular with viewers, showcasing Dempster's performance abilities. The film's exploration of urban poverty resonated with working-class audiences, though its romantic elements appealed more to middle-class viewers. Over time, the film has largely faded from public consciousness, known primarily among silent film enthusiasts and Griffith scholars. Modern audiences who have seen the restored version often express appreciation for its atmospheric qualities while noting its dated elements.

Awards & Recognition

- No major awards were recorded for this film

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Broken Blossoms (1919) - Griffith's own earlier film about interracial romance in London

- The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) - for expressionistic lighting techniques

- Way Down East (1920) - Griffith's previous film exploring similar themes of female virtue

This Film Influenced

- The Wind (1928) - for its atmospheric depiction of harsh environments

- Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927) - for urban romance themes

- The Crowd (1928) - for its portrayal of urban life

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is partially preserved with incomplete versions held in several archives. The original sound version is considered lost, while silent versions survive at the Library of Congress, the Museum of Modern Art, and the UCLA Film and Television Archive. The most complete version runs approximately 58 minutes, missing some footage from the original 70-minute release. Some scenes exist only in fragmentary form. The George Eastman Museum holds a restored version with tinted elements. Preservation efforts have been ongoing, though the incomplete nature of surviving materials makes full restoration impossible.