Earth

"The earth belongs to everyone"

Plot

In a Ukrainian village during the early Soviet period, young Komsomol member Vasyl returns with the community's first tractor, symbolizing the dawn of collectivization. With revolutionary zeal, Vasyl and his supporters use the tractor to plow down the private property boundaries that separate individual plots, angering the wealthy kulaks who resist collectivization. The kulaks, led by Khoma, plot against Vasyl and ultimately murder him in a brutal attack, but his martyrdom only strengthens the villagers' resolve. Despite Vasyl's tragic death, the collective farm (kolkhoz) is successfully established, with the film ending with a joyous celebration of the new communal life juxtaposed with Vasyl's funeral procession. The closing scenes feature Vasyl's grieving father accepting the new order and finding solace in the natural world, suggesting the eternal cycle of life and death.

About the Production

Filmed during the height of Stalin's collectivization campaign, the production faced significant political pressure. Many of the 'actors' were actual peasants from local villages, adding authenticity to the performances. The production team faced technical challenges with the imported Fordson tractor, which frequently broke down during filming. Dovzhenko had to make extensive cuts to appease Soviet censors who initially found the film 'too poetic' and 'insufficiently political.' The famous apple sequence was added late in production after Dovzhenko's wife suggested the film needed more symbolic imagery.

Historical Background

Earth was produced during Stalin's First Five-Year Plan (1928-1932), a period of rapid industrialization and forced collectivization that transformed Soviet society. The film captures the intense ideological battle between traditional peasant life and Soviet modernization, reflecting the real-world conflict between kulaks (wealthy peasants) and collectivization efforts. Made just before the catastrophic Holodomor (1932-1933), the Ukrainian famine that killed millions, the film's celebration of collectivization takes on tragic irony in hindsight. The late 1920s also saw the transition from silent to sound cinema, making Earth one of the last major silent productions and representing the pinnacle of silent Soviet artistry. The film emerged from the vibrant Ukrainian cultural renaissance of the 1920s, which was soon to be crushed by Stalinist repression. Dovzhenko was working within the constraints of Socialist Realism while trying to maintain artistic integrity, a balance that became increasingly impossible as the 1930s progressed.

Why This Film Matters

Earth stands as one of the most influential films in cinema history, revolutionizing visual storytelling through its poetic approach to political themes. The film transcended its propaganda purpose to become a universal meditation on life, death, and humanity's relationship with nature. Its innovative use of montage, symbolic imagery, and lyrical pacing influenced generations of filmmakers worldwide, from Sergei Parajanov to Andrei Tarkovsky. The film represents a unique synthesis of Ukrainian folk culture, Soviet ideology, and avant-garde artistic expression. It preserved elements of Ukrainian identity at a time when Soviet policy sought to suppress national cultures. Earth's visual language, particularly its treatment of landscape as character, has been referenced in countless films about rural life and social transformation. The film continues to serve as a testament to the possibility of creating art of universal value within political constraints, and its themes of modernization versus tradition remain relevant in contemporary discussions about agricultural policy and rural development.

Making Of

The production of 'Earth' occurred during one of the most turbulent periods in Soviet history. Dovzhenko, though a committed communist, struggled to balance artistic vision with political requirements. He frequently clashed with VUFKU officials and Soviet censors who demanded clearer propaganda messaging. The casting process was unusual - Dovzhenko sought authentic faces rather than professional actors, recruiting many peasants from nearby collective farms. The film's most controversial sequence showing Vasyl's naked body after death was nearly cut entirely. Dovzhenko fought to keep it, arguing it symbolized the unity of man with nature. The production faced numerous technical difficulties; the primitive camera equipment often failed in the harsh Ukrainian climate, and the crew had to improvise solutions. Despite these challenges, Dovzhenko's innovative approach to cinematography and his poetic vision resulted in what many consider his masterpiece.

Visual Style

The cinematography of Earth, led by Danylo Demutskyi, revolutionized visual storytelling through its innovative use of landscape as narrative element. The film employs sweeping shots of Ukrainian fields that serve both as beautiful imagery and as symbols of the land's importance to the people. Demutskyi and Dovzhenko developed a unique visual language using deep focus, dramatic low angles, and expressive close-ups that capture both the grandeur of nature and intimate human emotions. The famous sequence of the apple falling from the tree demonstrates their mastery of symbolic imagery, using simple natural events to convey profound philosophical ideas. The film's visual style combines documentary realism with poetic abstraction, creating scenes that feel both authentic and mythic. The cinematography makes innovative use of natural light, particularly in outdoor scenes where the changing Ukrainian sky becomes part of the narrative. The camera work during the tractor sequence creates a sense of mechanical power overwhelming traditional ways of life, while the funeral procession scenes use slow, solemn movements to convey collective grief.

Innovations

Earth pioneered several technical innovations that influenced cinema for decades. The film's editing techniques, particularly its use of rhythmic montage to create emotional and symbolic meaning, advanced beyond the political montage of Eisenstein to create a more poetic form of expression. The production team developed new methods for outdoor location shooting in difficult weather conditions, creating portable equipment modifications that allowed filming in remote Ukrainian villages. The film's special effects, while simple by modern standards, were innovative for their time, particularly in the sequence showing the tractor's supernatural power as it breaks through boundaries. The cinematography employed experimental techniques including extreme close-ups of natural elements and innovative camera movements that created a sense of organic flow. The film's preservation and restoration over the decades have also contributed to technical knowledge about preserving nitrate film stock. Earth's visual effects in the death scene, using superimposition and creative lighting, created haunting imagery that influenced horror and art cinema. The production team's ability to achieve professional results with limited resources demonstrated remarkable technical ingenuity.

Music

As a silent film, Earth originally relied on live musical accompaniment during screenings, with theaters providing their own scores. The first official composed score was created by Vyacheslav Ovchinnikov in the 1970s for a restored version of the film. Various composers have since created new scores for different restorations and screenings, including modern interpretations by contemporary artists. The most acclaimed modern score was composed by Michael Nyman in the 1990s, which emphasized the film's poetic qualities while respecting its Soviet origins. Some screenings feature traditional Ukrainian folk music, connecting the film to its cultural roots. The absence of dialogue in the original version forces viewers to focus on visual storytelling, making the musical accompaniment particularly important in setting emotional tone. Recent digital restorations have included multiple soundtrack options, allowing viewers to experience the film with different musical interpretations. The sound design in later versions includes subtle natural sounds that enhance the film's connection to the earth and rural life.

Famous Quotes

"The earth belongs to everyone" (opening intertitle)

"We will build a new life" (Vasyl's declaration)

"The sun rises for everyone" (closing intertitle)

"Death is not the end" (narrative intertitle)

"The tractor will bring us happiness" (villager's intertitle)

"We must break the old boundaries" (Vasyl's intertitle)

"The kulak is the enemy of progress" (party official's intertitle)

"From the earth we come, to the earth we return" (philosophical intertitle)

Memorable Scenes

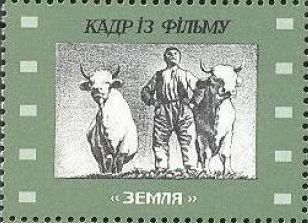

- The dramatic arrival of the tractor in the village, with peasants running alongside in awe and excitement

- Vasyl's passionate speech about collectivization, silhouetted against the Ukrainian sky

- The iconic sequence of the apple falling from the tree after Vasyl's death, symbolizing the cycle of life

- The powerful montage of the tractor breaking through property boundaries, accompanied by rhythmic editing

- Vasyl's murder scene, shot with haunting chiaroscuro lighting that creates a sense of tragic inevitability

- The extended funeral procession, with villagers carrying Vasyl's body through the fields he helped transform

- The final celebration of the collective farm, juxtaposing joy and grief in a complex emotional tableau

- The elderly father's silent communion with nature, finding peace in the earth that claimed his son

- The symbolic scene of sunflowers turning toward the light, representing hope and renewal

- The closing montage of faces, young and old, suggesting the continuity of life and the revolutionary struggle

Did You Know?

- This was the third and final part of Dovzhenko's 'Ukrainian Trilogy,' following 'Zvenigora' (1928) and 'Arsenal' (1929)

- Charlie Chaplin considered 'Earth' one of his favorite films and praised its poetic vision

- The film was initially condemned by Soviet authorities for 'formalism' and 'nationalist deviation' and was nearly banned

- The tractor used in the film was an actual Fordson imported from America, symbolizing Soviet industrialization

- Director Dovzhenko's wife, Yuliya Solntseva, not only starred in the film but also served as assistant director

- The famous scene of the apple falling from the tree was inspired by Newton and became one of cinema's most enduring metaphors

- The film was one of the last major Soviet silent productions, released just as sound cinema was taking over

- In 1958, 'Earth' was named one of the 12 greatest films of all time at the Brussels World's Fair

- Many of the outdoor scenes were shot in extreme weather conditions, with cast and crew enduring harsh Ukrainian winters

- The film's title 'Zemlya' (Earth) refers both to the physical land and to the spiritual connection Ukrainians have with their soil

- Dovzhenko faced threats of arrest during production due to the film's perceived insufficient ideological clarity

What Critics Said

Initial Soviet reception was mixed to hostile, with critics like Viktor Shklovsky praising its artistry while party officials condemned it as 'formalist' and ideologically suspect. Pravda initially criticized the film for focusing too much on nature and not enough on class struggle. However, international critics immediately recognized its genius, with foreign reviews hailing it as a masterpiece of poetic cinema. Over time, Soviet critical opinion evolved, and by the 1950s, Earth was celebrated as a classic of Soviet cinema. Modern critics universally praise the film as one of the greatest ever made, with particular admiration for its visual poetry and complex treatment of political themes. The film is now studied in film schools worldwide as a prime example of how political cinema can achieve artistic transcendence. Contemporary scholars continue to debate the film's relationship to Soviet ideology, with some seeing it as subversive and others as genuine propaganda elevated to art.

What Audiences Thought

Initial Soviet audience reactions were divided - some peasants found the film authentic and moving, while urban viewers sometimes found it too slow and poetic. The film's abstract symbolism confused many viewers expecting straightforward propaganda. International audiences, particularly at European film festivals, responded more enthusiastically to its artistic merits. Over decades, Earth has gained appreciation from global cinema enthusiasts, who now recognize it as a groundbreaking work. Modern audiences often find the film visually stunning and emotionally powerful, though some struggle with its slow pacing by contemporary standards. The film has developed a cult following among cinephiles and is frequently screened at art house cinemas and film retrospectives. Ukrainian audiences today view the film with complex emotions, recognizing both its artistic brilliance and its problematic relationship to the tragic history of collectivization.

Awards & Recognition

- Named one of the 12 greatest films of all time, Brussels World's Fair (1958)

- Voted among the top 10 films in Sight & Sound's critics' poll (multiple times)

- Special recognition at the Venice Film Festival retrospective (1970)

- Honored at the Moscow International Film Festival retrospective (1959)

- Included in the UNESCO Memory of the World Register (1994)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Soviet montage theory (Eisenstein, Pudovkin, Vertov)

- Ukrainian folk traditions and mythology

- Marxist-Leninist ideology

- European avant-garde cinema of the 1920s

- German Expressionism

- Ukrainian poetry and literature

- Documentary realism

- Symbolist art and literature

- Traditional Ukrainian visual arts

- Political theater of the 1920s

This Film Influenced

- Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors (1964)

- The Color of Pomegranates (1969)

- Stalker (1979)

- The Ascent (1977)

- Come and See (1985)

- Urga (1991)

- The Wind That Shakes the Barley (2006)

- The Milk of Sorrow (2009)

- Leviathan (2014)

- Atlantis (2019)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Earth has been preserved through multiple restoration projects, though some original footage remains lost. The film exists in various versions, with different running times reflecting cuts made for different audiences. The most complete restoration was undertaken by the Gosfilmofond of Russia in collaboration with international archives. The British Film Institute and the Criterion Collection have both produced restored versions with improved image and sound quality. Original nitrate elements are preserved in Russian and Ukrainian state archives. The film was added to the UNESCO Memory of the World Register in 1994, ensuring its preservation for future generations. Digital restoration efforts in the 2010s used advanced technology to repair damage and enhance visual clarity while maintaining the film's original aesthetic. Some scenes exist only in lower-quality copies, as original negatives were lost during World War II. The film's preservation has been prioritized by international film organizations due to its historical and artistic significance.