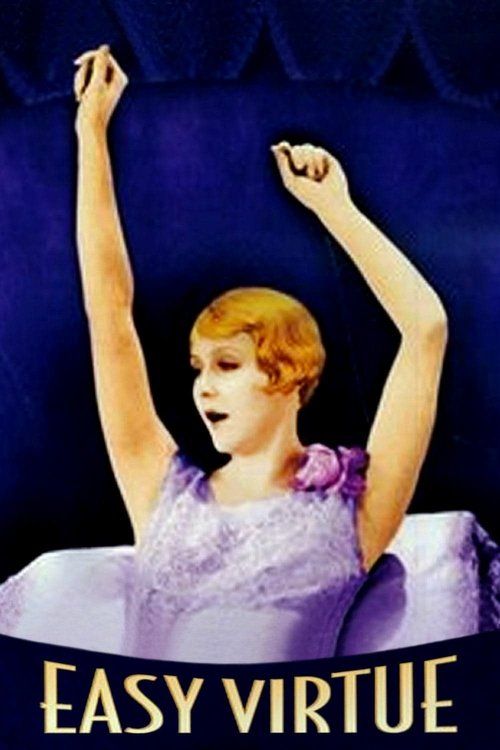

Easy Virtue

"A woman with a past... a man without a future!"

Plot

Larita Filton, a young British woman, finds herself at the center of a scandalous divorce trial when her husband accuses her of adultery. Despite her innocence, the sensationalized media coverage and public condemnation force her to flee England for the French Riviera, where she adopts a new identity. There, she meets and falls deeply in love with John Whittaker, a naive and wealthy young Englishman vacationing with his mother. After a whirlwind romance, they marry and return to England to meet John's disapproving aristocratic family, who immediately sense something amiss about Larita's past. As Larita struggles to fit into the rigid social expectations of the Whittaker household, her secret begins to unravel when a journalist recognizes her and threatens to expose her history, leading to a dramatic confrontation that tests the strength of their marriage and challenges the hypocrisies of British high society.

About the Production

This was Hitchcock's fifth film as director and his first adaptation of a Noël Coward work. The production faced challenges with British censorship boards due to its controversial themes of divorce and sexual double standards. Hitchcock employed innovative visual techniques including subjective camera angles and symbolic imagery to convey Larita's emotional state. The film was shot during the transition period from silent to sound cinema, which affected its commercial prospects. Hitchcock made significant changes from Coward's original play, adding visual storytelling elements and altering the ending to be more cinematic.

Historical Background

Easy Virtue was produced during a pivotal moment in both British cinema and society. 1928 was the final year of the silent film era, with 'The Jazz Singer' having already revolutionized the industry with sound. Britain was still recovering from World War I, and the film's themes of social change and questioning traditional values resonated with a society in transition. The 1920s saw the emergence of the 'flapper' generation and changing attitudes toward women's roles and sexuality, though conservative forces still dominated British culture. The film's treatment of divorce was particularly timely, as divorce rates were rising but remained socially stigmatized. In cinema, Hitchcock was part of a new generation of British directors working to establish a national film industry that could compete with Hollywood. British International Pictures, the production company, was one of the major studios attempting to create a sustainable British film culture. The film's release coincided with the passage of the Cinematograph Films Act of 1927, which was designed to protect and promote British cinema through quotas and exhibition requirements.

Why This Film Matters

Easy Virtue represents an important early example of Hitchcock's thematic preoccupations with social hypocrisy, the persecution of innocent protagonists, and the dark underbelly of respectable society. The film's critique of sexual double standards and social judgment was unusually progressive for its time, particularly in its sympathy for a woman judged for her sexuality. It demonstrates Hitchcock's early mastery of visual storytelling and his ability to convey complex psychological states through cinematic techniques rather than dialogue. The film is also significant as one of the earliest adaptations of Noël Coward's work to screen, helping to establish the pattern of translating theatrical wit to visual cinema. Its preservation and restoration have made it an important document of late silent era British filmmaking, showcasing the technical and artistic sophistication achieved before the transition to sound. The film's themes continue to resonate today, making it relevant to discussions about media sensationalism, public shaming, and the enduring power of social judgment.

Making Of

The production of 'Easy Virtue' marked a significant period in Hitchcock's career as he transitioned from novice director to established filmmaker. Working under contract with British International Pictures, Hitchcock had more creative freedom than on his earlier films. The adaptation process was challenging, as Noël Coward's play relied heavily on witty dialogue that couldn't be translated to silent film. Hitchcock and his screenwriters, Eliot Stannard and Michael Morton, had to invent visual equivalents for Coward's verbal sophistication. The director experimented with subjective camera techniques, particularly in the courtroom sequences where he used camera angles to reflect Larita's sense of being judged and trapped. The production team created elaborate sets to represent both the French Riviera and English country houses, though budget limitations meant many exteriors were shot on studio backlots. The film's controversial subject matter led to extensive negotiations with British censors, who demanded cuts to certain scenes they deemed too suggestive. Hitchcock fought to maintain the film's critical perspective on social hypocrisy, eventually reaching a compromise that preserved the core themes while satisfying censorship requirements.

Visual Style

The cinematography, handled by Jack E. Cox, demonstrates remarkable sophistication for a late silent film. Cox employed innovative camera techniques including subjective angles to represent Larita's psychological state, particularly during the courtroom scenes where low angles convey her sense of being overwhelmed by judgment. The film uses chiaroscuro lighting to create emotional atmosphere, with Larita often shot in soft focus during moments of vulnerability. The French Riviera sequences feature bright, high-key lighting to represent freedom and possibility, while the English country house scenes are dominated by darker, more constrained lighting reflecting social oppression. Cox utilized moving camera shots, which were still relatively uncommon in 1928, particularly in the tracking shots that follow Larita through the various social spaces. The film's visual composition frequently uses architectural elements to trap or frame characters, reinforcing themes of social confinement. The cinematography also incorporates symbolic imagery, including recurring motifs of mirrors and reflections to explore questions of identity and social perception.

Innovations

Easy Virtue showcased several technical innovations that were advanced for 1928. Hitchcock employed sophisticated editing techniques, including cross-cutting between past and present to reveal Larita's backstory through visual rather than expository means. The film features complex camera movements, including tracking shots that follow characters through spaces, creating a sense of continuous action and psychological immersion. The production used innovative special effects for certain sequences, particularly in the courtroom scenes where superimposition techniques were used to show press headlines and public reaction. The film's set design incorporated movable elements to allow for more dynamic camera movement and blocking. Hitchcock experimented with subjective point-of-view shots, placing the camera in positions that would later become hallmarks of his style. The film's editing rhythm was particularly sophisticated, with Hitchcock using varying shot lengths to control pacing and emotional intensity. The technical team also developed new techniques for creating the illusion of outdoor spaces within studio constraints, using painted backdrops and forced perspective.

Music

As a silent film, Easy Virtue originally featured live musical accompaniment that varied by theater. The typical score would have included classical pieces and popular songs of the era, selected to match the film's emotional tone. For the French Riviera sequences, theaters likely used lighter, more romantic music, while the dramatic confrontation scenes would have featured more intense classical compositions. When the film was restored in the 1980s, a new musical score was commissioned to accompany it for modern screenings. The contemporary score typically draws from 1920s popular music and light classical pieces to maintain the film's period atmosphere while enhancing the emotional narrative. The restored version's soundtrack has been praised for its sensitivity to the film's visual rhythms and emotional beats. Some modern screenings feature live musical accompaniment by silent film specialists who improvise based on the film's visual cues and emotional progression.

Famous Quotes

As a silent film, Easy Virtue contains no spoken dialogue, but features notable intertitles including: 'A woman's reputation is the one thing that can never be restored once it is lost.'

Intertitle during courtroom scene: 'The truth is no defense against public opinion.'

Opening intertitle: 'Some women are born to trouble - others find it without trying.'

Intertitle reflecting Larita's thoughts: 'In trying to escape my past, I have only found another prison.'

Concluding intertitle: 'Society forgives a man anything - but a woman, nothing.'

Memorable Scenes

- The opening courtroom sequence where Larita is publicly shamed and judged, using innovative camera angles and editing to convey her sense of entrapment and humiliation

- The romantic meeting on the French Riviera where Larita and John first connect, featuring bright, optimistic cinematography that contrasts with later scenes

- The tense dinner scene at the Whittaker family home where Larita's presence creates palpable tension, demonstrated through blocking and composition

- The final confrontation scene where Larita's past is revealed, featuring rapid editing and dramatic close-ups to heighten emotional intensity

- The symbolic mirror sequence where Larita confronts her changing identity through reflections

Did You Know?

- This was Alfred Hitchcock's first adaptation of a Noël Coward play, though he would later work with Coward again on 'The Man Who Knew Too Much' (1934)

- The film was considered quite controversial for its time due to its frank depiction of divorce and sexual double standards

- Isabel Jeans reprised her stage role from the original West End production of Coward's play

- The original play was only 30 minutes long, requiring Hitchcock to significantly expand the story for feature length

- Hitchcock makes his traditional cameo appearance approximately 12 minutes into the film, walking past a tennis court

- The film was one of the last major British silent productions before the industry fully transitioned to sound

- Coward reportedly disliked Hitchcock's adaptation, feeling it lost the wit and sophistication of his original work

- The film's negative was considered lost for decades until a complete print was discovered in the 1970s

- The movie's themes of social hypocrisy and judgment of women's sexuality were unusually progressive for 1928

- The French Riviera sequences were actually filmed on studio sets due to budget constraints

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception was mixed, with many reviewers praising Hitchcock's technical direction but questioning the suitability of Coward's sophisticated play for silent adaptation. The Times noted that 'Hitchcock has done wonders with visual storytelling, but something of Coward's sparkle is inevitably lost in translation.' The Picturegoer magazine praised Isabel Jeans' performance as 'emotionally powerful and visually compelling.' Modern critics have reevaluated the film more favorably, with many considering it an underrated gem in Hitchcock's early filmography. The British Film Institute describes it as 'a visually sophisticated treatment of social hypocrisy that showcases Hitchcock's emerging mastery of cinematic language.' Film scholars have noted the film's innovative use of subjective camera angles and symbolic imagery as evidence of Hitchcock's developing artistic vision. The restoration in the 1980s allowed contemporary critics to fully appreciate the film's technical achievements and thematic depth.

What Audiences Thought

Initial audience reception in Britain was moderate, with the film finding more success with urban, sophisticated viewers who appreciated its social commentary. The controversial subject matter limited its appeal in more conservative markets, particularly in smaller towns where the themes of divorce and sexual scandal were considered inappropriate. The film performed better in London and other major cities where audiences were more accustomed to European cinema and more liberal social attitudes. International reception was limited, as the distinctly British social concerns didn't always translate to other markets. The transition to sound cinema shortly after its release also affected its long-term theatrical run. Modern audiences, particularly Hitchcock enthusiasts and silent film aficionados, have shown renewed interest in the film following its restoration and availability on home video and streaming platforms. Many contemporary viewers express surprise at the film's progressive themes and sophisticated visual storytelling for its era.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- German Expressionist cinema (particularly in visual style and psychological emphasis)

- Noël Coward's original 1924 stage play

- The social problem films of Victorian and Edwardian British literature

- F.W. Murnau's visual storytelling techniques

- The tradition of British social realism in theater and literature

This Film Influenced

- Hitchcock's later films dealing with wrongfully accused protagonists

- British social dramas of the 1930s

- Later adaptations of Noël Coward works

- Films exploring media sensationalism and public shaming

- The 2008 remake starring Jessica Biel

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

For decades, Easy Virtue was considered a lost film, with only fragments known to exist. A complete 35mm print was discovered in the 1970s in a private collection, though it showed signs of deterioration. The film was subsequently restored by the British Film Institute in the 1980s, with missing footage reconstructed from production stills and existing fragments. The restored version represents approximately 85% of the original film, with brief gaps where footage remains missing. The restoration has been preserved in the BFI National Archive and has been made available for theatrical screenings and home video distribution. Digital restoration in the 2000s further improved the image quality and stability. The film is now considered well-preserved compared to many other silent films of its era, though some sequences still show the effects of age and incomplete source material.