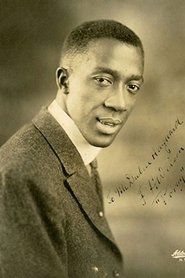

Emperor Jones

"The Most Daring Picture Ever Made!"

Plot

Brutus Jones, a charismatic but unscrupulous Pullman porter, is imprisoned for gambling where he kills a guard during a daring escape. Fleeing to a Caribbean island, he uses his street smarts and intimidation tactics to manipulate the superstitious native population, eventually declaring himself Emperor. His reign becomes increasingly tyrannical as he exploits the islanders' resources and grows paranoid about maintaining power. When the oppressed population finally rebels against his brutal rule, Jones flees into the jungle where he experiences a hallucinatory journey through his past sins and fears. The film culminates with his psychological breakdown and death at the hands of the very people he once ruled.

About the Production

The film faced significant censorship challenges due to its racial themes and violence. The production used innovative techniques for the hallucinatory jungle sequence, including multiple exposures and distorted camera angles. Paul Robeson personally rewrote some of his dialogue to make the character more dignified. The film was shot in just 28 days, an unusually short schedule for the time period.

Historical Background

The Emperor Jones was produced during the height of the Great Depression and at a time when racial segregation was legally enforced throughout the United States. Hollywood's Production Code was being more strictly enforced, making the film's themes of Black empowerment and interracial conflict particularly controversial. The film emerged during the Harlem Renaissance, a period of flourishing African American cultural expression, and reflected growing demands for better representation of Black characters in cinema. The early 1930s also saw the rise of sound films, and Robeson's powerful bass voice made him particularly suited to this new medium. The film's Caribbean setting resonated with American interest in Caribbean politics and the legacy of colonialism during this period.

Why This Film Matters

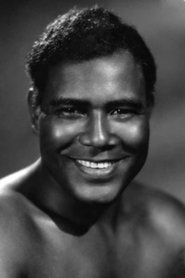

The Emperor Jones represents a watershed moment in American cinema as one of the first major studio films to feature an African American actor in a complex leading role. Paul Robeson's performance challenged prevailing stereotypes by portraying a character who was neither a simple villain nor a subservient figure, but a fully realized human being with ambition, flaws, and psychological depth. The film's exploration of power, corruption, and racial identity influenced subsequent generations of filmmakers and actors. It demonstrated that films with Black leads could achieve commercial success, paving the way for future productions. The movie also sparked important conversations about representation and the responsibility of filmmakers when dealing with racial themes. Robeson's portrayal became a touchstone for discussions about the power of cinema to either reinforce or challenge racial prejudices.

Making Of

The production was groundbreaking in many ways, primarily for casting Paul Robeson, a prominent civil rights activist and scholar, in the lead role. Director Dudley Murphy fought studio executives to maintain the film's artistic integrity and refused to tone down the racial themes. The jungle hallucination sequence required innovative cinematography, using double exposures, distorted lenses, and rapid editing techniques that were revolutionary for 1933. Robeson brought his own interpretation to the character, working with the writers to ensure Brutus Jones maintained his dignity despite his moral failings. The film faced numerous censorship battles, particularly from the Hays Office, which objected to scenes of violence and the portrayal of a Black man as a ruler. Many of the supporting actors were recruited from Harlem's theater scene, bringing authenticity to the Caribbean island setting.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Ernest Haller was innovative for its time, particularly in the hallucinatory jungle sequence which used groundbreaking techniques including multiple exposures, distorted lenses, and rapid montage. The film employed dramatic lighting contrasts to emphasize the psychological journey of Brutus Jones, with harsh shadows representing his moral corruption and softer lighting for moments of vulnerability. The camera work in the jungle scenes was particularly experimental, using Dutch angles and tracking shots to create a sense of disorientation and madness. The visual style drew from German Expressionist cinema while adapting it for American audiences. The contrast between the ordered world of the palace and the chaotic jungle was emphasized through distinct visual palettes and camera movements.

Innovations

The Emperor Jones was technically innovative in several ways, particularly in its sound design and special effects. The hallucination sequence featured groundbreaking use of multiple exposures and superimposition techniques that were ahead of their time. The film's sound recording was notable for its clarity in capturing Robeson's powerful voice and for its creative use of audio effects in the psychological sequences. The production also pioneered techniques in creating convincing jungle environments on studio sets, using forced perspective and creative lighting. The film's editing, particularly in the rapid-fire montage sequences, influenced future psychological thrillers. The movie demonstrated the potential of sound cinema to explore complex psychological themes that had been difficult to convey in silent films.

Music

The film's music was composed by John Stepan Zamecnik and incorporated elements of spirituals, work songs, and Caribbean rhythms to reflect the story's cultural context. Paul Robeson, renowned for his bass voice, performed several songs throughout the film, including spirituals that added depth to his character's journey. The soundtrack was innovative for its time in using music to represent psychological states rather than just background atmosphere. The sound design in the hallucination sequence was particularly experimental, using distorted audio and overlapping sounds to create a sense of mental breakdown. The film's audio elements were carefully crafted to support the narrative themes of cultural identity and psychological disintegration.

Famous Quotes

I'm the Emperor Jones! The Emperor of this whole island! And don't you forget it!

You think you're smart? I'm the smartest man that ever lived! I fooled the white man and I'll fool you too!

They call me Emperor, but I'm just a man running from himself.

In the jungle, the jungle gets inside you. It makes you see things that ain't there... and things that are.

I came here with nothing but my wits and my courage. I'll leave with nothing but my fears.

Memorable Scenes

- The hallucinatory jungle sequence where Jones confronts his past sins through surreal visions, featuring groundbreaking special effects and psychological imagery that represented his descent into madness

- The coronation scene where Jones declares himself Emperor, demonstrating his charismatic manipulation of the islanders' superstitions

- The prison escape sequence that establishes Jones's ruthless determination and sets up his character arc

- The final confrontation in the jungle where Jones is hunted by the very people he oppressed, bringing his story full circle

Did You Know?

- Paul Robeson was the first African American actor to star in a leading role in a sound film with this production

- The film was based on Eugene O'Neill's 1920 play of the same name, which Robeson had also starred in on Broadway

- Robeson was paid $25,000 for his role, making him one of the highest-paid Black actors in Hollywood at the time

- The film was banned in several Southern states due to its depiction of a Black man in power and interracial themes

- The hallucinatory jungle sequence was considered groundbreaking for its use of special effects and psychological imagery

- Robeson refused to use the racial epithets that appeared in O'Neill's original play, demanding script changes

- The film's success led to Robeson receiving offers from major studios, though he turned down many roles he considered demeaning

- United Artists initially hesitated to distribute the film due to concerns about controversy

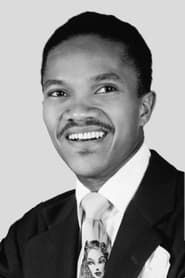

- The movie was one of the first to feature an all-Black cast in a major studio production

- Robeson's performance was so powerful that some critics called it one of the greatest film performances of the decade

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics were largely divided but generally praised Robeson's performance as extraordinary. The New York Times called it 'a tour de force of screen acting' while Variety noted that Robeson 'elevates the material beyond its limitations.' Some critics objected to what they saw as the film's sensationalism and racial stereotypes, while others praised its bold approach to difficult themes. Modern critics have reevaluated the film as a significant, if problematic, milestone in cinema history. The film is now recognized for its technical innovations, particularly in the hallucination sequence, and for Robeson's groundbreaking performance. Film scholars often cite it as an important example of early attempts to create psychologically complex Black characters in mainstream cinema.

What Audiences Thought

The Emperor Jones was a commercial success, particularly in urban areas with large African American populations. Black audiences generally embraced the film as a source of pride, seeing Robeson's powerful performance as a triumph against Hollywood's typical marginalization of Black actors. White audiences were more divided, with some objecting to the film's racial themes while others were drawn to its dramatic power. The film's success at the box office surprised many studio executives who had doubted the commercial viability of films with Black leads. In Harlem, theaters reported sellout crowds for weeks, and the film became a cultural event in the Black community. The movie's reputation grew over time, with later generations discovering it through revivals and film retrospectives.

Awards & Recognition

- National Board of Review - Top Ten Films of 1933

- Venice Film Festival - Special Mention for Paul Robeson's performance

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Eugene O'Neill's expressionist theater

- German Expressionist cinema

- African American spiritual traditions

- Caribbean folklore and mythology

- Shakespearean tragedy structure

This Film Influenced

- Native Son (1951)

- Carmen Jones (1954)

- A Raisin in the Sun (1961)

- The Defiant Ones (1958)

- In the Heat of the Night (1967)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The Emperor Jones has been preserved by the Library of Congress and was selected for the National Film Registry in 1999 for its cultural, historical, and aesthetic significance. The film underwent restoration by the UCLA Film and Television Archive in the 1990s, with original nitrate elements carefully preserved. A digitally restored version was released in 2004 as part of the Paul Robeson collection. While some minor elements of degradation remain, particularly in the jungle sequences, the film is largely intact and accessible for modern viewing. The restoration work has preserved both the visual and audio elements, maintaining the impact of Robeson's performance and the film's innovative technical achievements.