Entr'acte

"A film of contradictions and agreements"

Plot

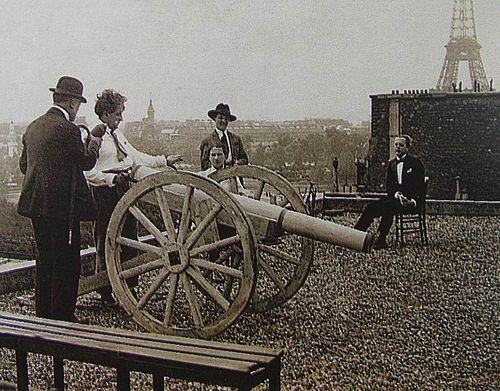

Entr'acte begins with a cannon fired from the roof of a building, setting in motion a series of absurdist vignettes that defy conventional narrative structure. The film features Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray playing chess on a Parisian rooftop, their game interrupted by a puff of smoke that transforms into a ballet dancer. We witness a hearse pulled by a camel being chased by pallbearers through the streets of Paris, a hunter tracking a feathered ostrich egg that hatches into a ballerina, and various other surreal sequences that play with speed, motion, and perception. The film culminates in a dizzying roller coaster ride that appears to threaten the audience itself, breaking the fourth wall in a revolutionary way. Throughout, the film employs experimental techniques including slow motion, fast motion, reverse motion, and stop-motion animation to create a dreamlike, nonsensical world that challenges viewers' expectations of cinema.

About the Production

Created as an intermission piece for the Ballets Suédois production of 'Relâche' at Théâtre des Champs-Élysées. The film was shot in just two days in November 1924. Many scenes were filmed on the rooftops of Paris and in the streets around Montmartre. The production involved prominent members of the Dada movement, with Francis Picabia serving as writer and artistic director alongside René Clair's direction.

Historical Background

Entr'acte was created during the height of the Dada movement in Paris, a period of intense artistic experimentation following World War I. The Dadaists, reacting against the rationalism and nationalism they believed led to the war, embraced absurdity, irrationality, and anti-art sentiments. Paris in the early 1920s was a melting pot of international artists, writers, and intellectuals, with figures like Picasso, Hemingway, Joyce, and Stravinsky all active in the city. The film emerged from this crucible of artistic rebellion, specifically from the Ballets Suédois, which had become a hub for avant-garde performance. The film's creation coincided with significant developments in cinema technology, including more portable cameras and film stocks, which enabled greater experimentation. It also reflected the growing influence of Freudian psychology and surrealist imagery in artistic circles. The post-war period saw a rejection of Victorian values and an embrace of modernity, speed, and technology, all themes that resonate throughout Entr'acte.

Why This Film Matters

Entr'acte represents a pivotal moment in cinematic history, marking one of the first truly avant-garde films and helping establish cinema as a legitimate artistic medium rather than mere entertainment. The film's rejection of narrative structure and its embrace of pure visual spectacle influenced generations of experimental filmmakers, from the Surrealists to the French New Wave. Its techniques of slow motion, fast motion, and reverse motion became standard tools in the cinematic vocabulary. The film's collaboration between different artistic disciplines prefigured multimedia art forms and the concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art). Entr'acte also exemplifies the Dadaist strategy of using humor and absurdity as political and social critique, a approach that would influence subsequent artistic movements from Surrealism to Situationism. The film's preservation and continued study demonstrate how avant-garde works, once considered ephemeral and disposable, can achieve lasting cultural significance. Its influence extends beyond cinema to music videos, advertising, and contemporary digital media that employ similar techniques of rapid cutting and visual discontinuity.

Making Of

Entr'acte emerged from the vibrant avant-garde scene of 1920s Paris, specifically from the collaboration between Francis Picabia (who wrote the scenario), René Clair (directing his first film), and Erik Satie (composing the score). The film was conceived as a deliberate attack on conventional cinema and bourgeois sensibilities, embodying the Dadaist philosophy of rejecting logic and reason. The production was remarkably spontaneous, with many scenes improvised on location. The famous rooftop chess scene between Duchamp and Man Ray was not staged but captured as the two artists genuinely played. The camel scene proved particularly challenging, as the animal proved difficult to control during filming. Clair employed innovative camera techniques, including mounting cameras on moving platforms and experimenting with various speeds, many of which were groundbreaking for the time. The collaboration between visual artists, musicians, and filmmakers represented a unique fusion of different artistic disciplines that characterized the avant-garde movement.

Visual Style

The cinematography of Entr'acte, primarily handled by Jimmy Berliet and Robert Guyer, was revolutionary for its time and remains visually striking today. The film employs a dizzying array of techniques including slow motion, fast motion, reverse motion, and stop-motion animation, often within the same sequence. The camera work is highly mobile, with tracking shots, Dutch angles, and unusual perspectives that contribute to the film's disorienting effect. The rooftop scenes make innovative use of Parisian architecture, creating striking visual compositions that play with depth and perspective. The cinematography deliberately breaks the rules of classical filmmaking, with jump cuts, mismatched shots, and deliberate continuity errors that reinforce the Dadaist rejection of conventional logic. The film's visual style ranges from documentary-like observation of real locations to highly stylized, almost abstract sequences. The use of extreme close-ups and distorted perspectives creates a sense of visual unease that complements the film's absurdist content. The black and white photography makes strong use of contrast and shadow, creating a graphic quality that enhances the film's surreal atmosphere.

Innovations

Entr'acte pioneered several technical innovations that would become standard in cinema. The film's extensive use of variable speed photography—ranging from extreme slow motion to rapid acceleration—was highly advanced for 1924. The cinematographers developed new techniques for mounting cameras on moving platforms to achieve dynamic tracking shots. The film's special effects, including the famous scene where a puff of smoke transforms into a dancer, were accomplished through in-camera techniques rather than post-production, requiring considerable technical ingenuity. The collaboration between live musicians and film projection represented an early form of multimedia synchronization. The film's editing style, with its rapid cuts and deliberate discontinuities, pushed the boundaries of what was considered acceptable in narrative cinema. The rooftop sequences required innovative camera rigging to achieve their distinctive perspectives. The roller coaster finale involved mounting cameras on the ride itself, creating a visceral sense of movement that was unprecedented. These technical achievements were particularly remarkable given the limited equipment available to independent filmmakers in the 1920s.

Music

The original score for Entr'acte was composed by Erik Satie, one of the most innovative composers of the early 20th century. Satie's music was groundbreaking in several respects: it was one of the first original scores composed specifically for a film, and it incorporated elements of jazz, popular music, and circus tunes alongside Satie's characteristically minimalist piano style. The score was structured to correspond with the film's visual rhythms, with Satie creating musical jokes and surprises that mirrored the film's visual gags. Notably, the score included parts for player piano, allowing for precise synchronization with the film's varying speeds. The original performance featured live musicians who would play during the film's screening, with the projectionist stopping the film at predetermined points to allow for musical transitions. Satie's score was lost for decades but was reconstructed from his manuscripts in the 1960s. The music embodies the same playful, anti-establishment spirit as the visuals, with its unexpected harmonic shifts and rhythmic surprises. Modern restorations of Entr'acte use reconstructed versions of Satie's score, though some screenings feature new compositions inspired by Satie's work.

Famous Quotes

'C'est un film de contradictions et d'accords' (It's a film of contradictions and agreements)

'The Dada spirit is the spirit of contradiction'

'Art is not serious. I assure you that if it were, we would have to find another name for it' - Francis Picabia about the film

'Cinema should be a visual experience, not a literary one' - René Clair

'We wanted to make a film that would be a pure visual spectacle, free from the constraints of narrative'

Memorable Scenes

- The opening cannon shot that launches the film into motion

- Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray playing chess on a Parisian rooftop

- The hearse pulled by a camel chased by pallbearers through Paris streets

- The hunter tracking an ostrich egg that hatches into a ballerina

- The dizzying roller coaster finale that appears to crash into the audience

- The puff of smoke transformation sequence

- The ballerina emerging from a champagne glass

- The synchronized diving sequence with multiple identical figures

Did You Know?

- The title 'Entr'acte' literally means 'between the acts' in French, reflecting its original purpose as an intermission piece

- The film was commissioned by Rolf de Maré, director of Ballets Suédois, to be shown during the intermission of the ballet 'Relâche'

- The word 'Relâche' means 'cancelled' or 'day off' in French, and the ballet itself was a Dadaist work that mocked traditional ballet

- Marcel Duchamp, who appears in the film playing chess, was one of the most influential figures in the Dada movement

- The famous opening cannon shot was inspired by the tradition of firing cannons to announce royal births

- The roller coaster finale was filmed on the Scenic Railway at Luna Park in Paris

- The film's score was composed by Erik Satie, who also composed the music for 'Relâche'

- Satie's score for Entr'acte was one of the first film scores composed specifically for a film

- The film was initially shown with the projectionist stopping the film at various points to allow Satie's live musicians to play

- Man Ray, who appears in the chess scene, was a pioneering Dada and Surrealist photographer

- The camel pulling the hearse was rented from a Parisian circus for the shoot

- The film was restored in 2004 by the Cinémathèque Française from original nitrate materials

What Critics Said

Initial critical reception to Entr'acte was divided, reflecting the controversial nature of Dadaist art. Mainstream critics were often bewildered or dismissive, with some dismissing it as meaningless nonsense. However, avant-garde circles immediately recognized its significance, with publications like Littérature and transition praising its revolutionary approach to cinema. Over time, critical opinion has shifted dramatically, and Entr'acte is now regarded as a masterpiece of early avant-garde cinema. Modern critics celebrate its technical innovation, its playful subversion of cinematic conventions, and its historical importance. The film is frequently cited in film studies as a crucial example of pure cinema and anti-narrative filmmaking. Contemporary scholars often analyze Entr'acte in the context of Dadaist philosophy, examining how its visual jokes and absurd sequences embody the movement's anti-rationalist stance. The film's restoration in 2004 brought renewed critical attention, with many reviewers noting how well its playful spirit and visual inventiveness have endured.

What Audiences Thought

The original audience for Entr'acte consisted primarily of the sophisticated, avant-garde crowd attending Ballets Suédois performances, many of whom were already familiar with Dadaist concepts. Their reception was generally enthusiastic, with many appreciating the film's humor and technical innovations. However, when the film was shown to more general audiences, reactions were often confused or hostile, with some viewers walking out or demanding their money back. Over the decades, as audiences became more accustomed to experimental cinema techniques, appreciation for Entr'acte has grown. Modern audiences viewing the film in film studies contexts or art cinema screenings tend to respond positively to its playful energy and historical significance. The film's brevity and visual humor make it more accessible than many other avant-garde works of the period. Today, Entr'acte is often enjoyed for its historical value as much as its artistic merits, with viewers fascinated by its glimpse into the revolutionary artistic world of 1920s Paris.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Dadaist art and philosophy

- Surrealist imagery

- Ballets Suédois productions

- Erik Satie's musical innovations

- Marcel Duchamp's readymades

- Man Ray's photography

- Francis Picabia's mechanistic art

- Futurist fascination with speed and motion

- Commedia dell'arte traditions of physical comedy

- Early cinema tricks by Georges Méliès

This Film Influenced

- Un Chien Andalou (1929)

- L'Âge d'Or (1930)

- Meshes of the Afternoon (1943)

- A Movie (1958)

- Scorpio Rising (1963)

- Wavelength (1967)

- La Jetée (1962)

- Screen (1970)

- Film (1965)

- The Last Days of Pompeii (2012)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Entr'acte has been well-preserved and restored. The original nitrate materials were preserved by the Cinémathèque Française, which conducted a major restoration in 2004. The restored version was scanned in high definition and has been included in numerous DVD and Blu-ray collections of avant-garde cinema. The film is considered to be in excellent condition for its age, with most sequences intact and clear. The restoration work has ensured that future generations will be able to study and enjoy this important work of early avant-garde cinema. The film is part of the permanent collections of several major film archives worldwide, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the British Film Institute.