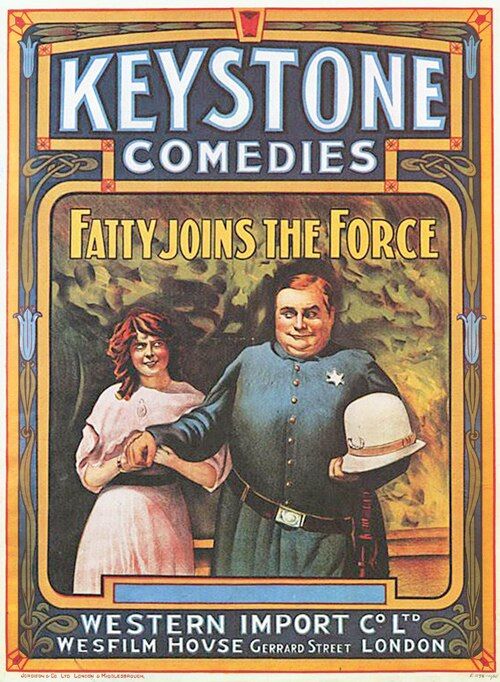

Fatty Joins the Force

"When Fatty becomes a cop, crime takes a holiday!"

Plot

In this classic Keystone comedy, Fatty (Roscoe Arbuckle) is a hapless young man who accidentally rescues the police commissioner's daughter from a runaway carriage, earning unexpected praise and a job offer as a police officer. Despite having no qualifications for law enforcement, Fatty accepts the position and immediately finds himself overwhelmed by the responsibilities and dangers of police work. His first assignment involves apprehending a group of thieves, but his bumbling nature and physical comedy lead to chaos rather than successful arrests. The film culminates in a wild chase sequence through the city streets where Fatty's incompetence somehow leads to the criminals' capture, albeit through pure accident rather than skill. By the end, Fatty has somehow managed to maintain his job despite demonstrating absolutely no aptitude for police work, reinforcing the film's comedic theme of the wrong man in the wrong profession.

About the Production

Filmed during Keystone's peak production period when they were releasing multiple shorts per week. The film was shot in just 1-2 days, typical for Keystone's rapid production schedule. The police uniforms were likely rented or borrowed props rather than custom-made. The chase sequence utilized real Los Angeles streets, creating authentic urban comedy settings that became a Keystone trademark.

Historical Background

1913 was a pivotal year in American cinema, marking the transition from short novelty films to more sophisticated narrative storytelling. The film industry was rapidly consolidating in Hollywood, with Keystone Studios leading the comedy genre. This was the year before Charlie Chaplin would join Keystone and revolutionize film comedy, so Arbuckle was one of the studio's major stars at the time. The film reflects the pre-World War I optimism and innocence of American culture, with its light-hearted treatment of authority figures like police officers. The motion picture industry was still establishing itself as a legitimate art form and business, with studios like Keystone pioneering production methods and distribution networks. 1913 also saw the rise of the feature film, though shorts like this one-reeler remained the dominant format for comedies. The film was made during the Progressive Era, when police reform was a real issue in American cities, adding an interesting layer to the comedy of incompetent law enforcement.

Why This Film Matters

This film represents an important early example of the 'fish out of water' comedy trope that would become a staple of American cinema. It helped establish Roscoe Arbuckle as a major comedy star before his later collaborations with Buster Keaton and his tragic downfall in the 1920s. The film's treatment of police authority as incompetent but well-meaning reflected Progressive Era attitudes toward institutional reform. As a Keystone production, it contributed to the development of American slapstick comedy, particularly the chase sequence format that would influence countless later films. The movie also represents an early example of physical comedy based on body type, with Arbuckle's size becoming central to his comic persona. The film's survival makes it an important historical document of early American comedy techniques and urban filming practices in the pre-Hollywood studio system era.

Making Of

The film was created during Mack Sennett's revolutionary period at Keystone, where he established the fast-paced, chaotic comedy style that would dominate American film comedy for years. George Nichols, the director, was one of Sennett's most reliable directors, capable of turning out quality comedies on extremely tight schedules. Arbuckle was still developing his screen persona at this point, having transitioned from stage work to film just the year before. The production utilized Keystone's signature approach of minimal scripting and maximum improvisation, allowing performers to create gags on set. The famous chase sequence was filmed guerrilla-style on Los Angeles streets without permits, a common practice for Keystone that often led to real confusion among bystanders who didn't realize they were watching a film being made. The relationship between Arbuckle and Durfee was genuine - they had married in 1908 and worked together frequently during this period, though their marriage would eventually end in divorce.

Visual Style

The cinematography was typical of Keystone productions in 1913, utilizing static cameras positioned for optimal viewing of the physical comedy. The film was shot in black and white on 35mm film, with the standard aspect ratio of the era. The camera work prioritized clarity of action over artistic composition, ensuring that gags and stunts were clearly visible to audiences. The chase sequence employed long takes to follow the action through streets, creating a sense of continuous movement. The lighting was natural and primarily outdoors, taking advantage of California sunshine. The cinematography, while technically simple by modern standards, was effective in capturing the rapid-paced comedy and spatial relationships essential to the gags.

Innovations

While not technically innovative, the film demonstrated Keystone's mastery of rapid production techniques and efficient location shooting. The chase sequence showed advanced understanding of spatial continuity and editing rhythm for comedy timing. The film's use of real urban locations for comedy represented an early example of location shooting becoming integral to narrative film. The physical stunts, while relatively simple by later standards, required careful timing and coordination that demonstrated the growing sophistication of film comedy techniques. The film's pacing and editing showed the emerging language of film comedy that would influence generations of filmmakers.

Music

As a silent film, 'Fatty Joins the Force' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during theatrical screenings. The typical accompaniment would have been a pianist or small theater orchestra playing popular music of the era, with selections chosen to match the mood of each scene. Chase sequences would have been accompanied by fast-paced, rhythmic music, while comic moments might have featured lighter, more whimsical tunes. No original score was composed specifically for this film, as was common practice for short comedies of this period. The music would have been selected from theater libraries or improvised by the musicians based on cue sheets provided by the studio or created by the musical director.

Famous Quotes

(Silent film - no dialogue, but intertitles would have included typical Keystone comedy text such as 'Fatty Saves the Day!' and 'Our Hero, the Policeman!')

Memorable Scenes

- The opening rescue sequence where Fatty accidentally saves the commissioner's daughter from a runaway carriage, establishing his undeserved hero status. The climactic chase through Los Angeles streets where Fatty's bumbling somehow leads to the criminals' capture, featuring multiple near-misses, collisions, and classic Keystone chaos with innocent bystanders getting caught up in the action.

Did You Know?

- This was one of the earliest films where Roscoe Arbuckle played a police officer, a character type he would revisit throughout his career

- Minta Durfee, who plays the commissioner's daughter, was Arbuckle's real-life wife at the time of filming

- Edgar Kennedy, who appears in the film, would later become famous as the 'Slow Burn' character in comedy shorts

- The film was produced during Keystone's first year of operation, when they were revolutionizing American comedy cinema

- Director George Nichols was a prolific Keystone director who worked extensively with both Arbuckle and Charlie Chaplin

- The runaway carriage sequence was performed without stunt doubles, with actors doing their own dangerous work

- Keystone's policy was to release films almost immediately after completion, sometimes within days of filming

- This film survives today in the Library of Congress collection, though some prints are incomplete

- The police station set was reused in multiple Keystone films to save production costs

- Arbuckle's character's weight was already a central comedic element, establishing his 'Fatty' persona early in his career

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews in trade publications like The Moving Picture World praised the film's energetic comedy and Arbuckle's performance. Critics noted the film's effective use of physical comedy and its well-executed chase sequence. The film was considered typical of Keystone's high-quality comedy output, with reviewers appreciating its fast pace and continuous gags. Modern film historians view the film as an important early example of Arbuckle's work and a representative sample of Keystone's house style. The film is often cited in studies of early American comedy as demonstrating the rapid development of film comedy techniques between 1912-1914. Critics today note how the film, while simple by modern standards, shows sophisticated understanding of visual comedy timing and spatial humor.

What Audiences Thought

The film was popular with audiences of 1913, who were growing accustomed to Keystone's brand of chaotic comedy. Arbuckle's relatable everyman character resonated with working-class audiences who found humor in the idea of an ordinary person suddenly elevated to a position of authority. The film's short length and continuous action made it ideal for the varied theater programs of the era. Audience reactions were typically enthusiastic, with reported laughter during screenings being a common measure of a comedy's success. The film's popularity helped establish Arbuckle as a bankable star for Keystone, leading to more starring vehicles for him in subsequent years. Modern audiences viewing the film in retrospectives and archives often appreciate its historical significance and the charm of early silent comedy.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Earlier Mack Sennett comedies

- French comedy films of the era

- Vaudeville comedy traditions

- Stage farce conventions

This Film Influenced

- Later Arbuckle police comedies

- Keystone cop films

- Charlie Chaplin's police comedies

- The Three Stooges shorts

- Laurel and Hardy police films

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in various archives including the Library of Congress and the Museum of Modern Art. While not considered lost, some prints are incomplete or in poor condition. The film has been included in several DVD collections of early comedy and Keystone shorts. Restoration efforts have preserved much of the film, though some deterioration is evident in existing prints. The survival of this 1913 one-reeler is notable given that many films from this early period have been completely lost.