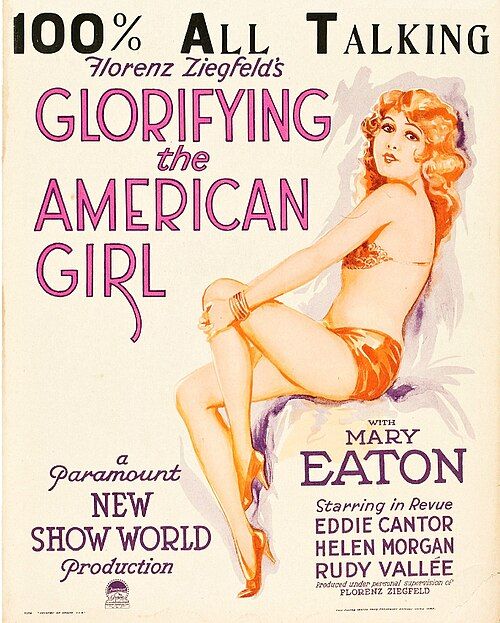

Glorifying the American Girl

"A Musical Romance of the Stage!"

Plot

Barbara (Mary Eaton) works in a department store's sheet music department, singing the latest hits while dreaming of stardom in the Ziegfeld Follies. Her childhood boyfriend Bill (Dan Healy) accompanies her on piano and loves her unrequitedly, but Barbara's single-minded focus on her career blinds her to his devotion. When vaudeville performer Patch Gallagher (Eddie Cantor) discovers her talent and offers her a partnership, Barbara sees it as her big break and follows him to New York City. Upon arrival, she discovers Gallagher's true intentions - he demands sexual favors as the price for making her a star, forcing Barbara to choose between her dreams and her integrity. Despite this setback, Barbara's exceptional talent is eventually recognized by a Ziegfeld representative, and she achieves her dream through merit rather than compromise, performing triumphantly in the Follies while finally appreciating Bill's unwavering love.

About the Production

This was one of Paramount's early all-talking musicals, filmed during the challenging transition from silent to sound. The production faced significant technical difficulties with early sound recording equipment, requiring microphones to be hidden in props and furniture, which restricted actor movement. The film was shot with Vitaphone sound-on-disc technology, and several musical numbers were recorded live with full orchestra, a technically ambitious feat for 1929. The production had direct cooperation from Florenz Ziegfeld himself, who allowed authentic recreation of his Follies production numbers.

Historical Background

The film was released in September 1929, during one of the most pivotal years in American history and cinema. This was the height of the transition from silent films to talkies, a technological revolution that was reshaping Hollywood and putting many silent film stars out of work while creating opportunities for stage performers like those featured in this film. The Roaring Twenties were in their final months, with the stock market crash of October 1929 looming just weeks after the film's release. The Great Depression that followed would dramatically alter American culture and the entertainment industry, making this film one of the last celebrations of Jazz Age optimism before the economic downturn fundamentally changed American values and entertainment preferences. The film captured the peak of the Broadway-to-Hollywood pipeline, when stage producers like Ziegfeld were actively collaborating with film studios to translate theatrical successes to the new medium of sound cinema.

Why This Film Matters

The film serves as an invaluable cultural document of the Ziegfeld Follies era, preserving the style, spectacle, and glamour of one of America's most influential theatrical productions. It represents a crucial moment in the development of the Hollywood musical genre, bridging the gap between Broadway revues and cinematic storytelling. The film's portrayal of a young woman navigating the entertainment industry while maintaining her moral integrity offered a progressive model of female empowerment for its time, reflecting the changing attitudes toward women's independence and career ambitions in the 1920s. Its backstage look at show business provided audiences with an insider's view of the entertainment industry that would become a popular genre convention. The film also documented the transition of performance styles from stage to screen, capturing how Broadway performers adapted their acting and singing techniques for the new medium of sound film.

Making Of

The production of 'Glorifying the American Girl' was exceptionally challenging due to the primitive state of sound technology in 1929. Director Millard Webb had to completely rethink his approach to filmmaking, as the cumbersome sound equipment severely limited camera movement and required actors to remain relatively stationary near hidden microphones. The Astoria Studios facility was one of the few in America equipped for sound production, and Paramount invested heavily in upgrading it for this production. The musical numbers presented particular difficulties, as the orchestra had to be recorded simultaneously with the performers, requiring precise timing and multiple takes. The Technicolor sequences required entirely different lighting setups and had to be filmed separately, adding to the production's complexity and budget. Florenz Ziegfeld's involvement ensured authenticity but also meant meeting his exacting standards for the recreation of his famous Follies productions. The cast, many of whom were Broadway veterans, had to adapt their stage performances to the more intimate requirements of the microphone, a transition that proved difficult for some performers used to projecting to the back rows of large theaters.

Visual Style

The cinematography by James Wong Howe demonstrated remarkable adaptation to the severe constraints of early sound filming. Camera movements were notably static compared to late silent films, as the need to keep microphones hidden and actors close to sound sources limited mobility. Howe employed creative solutions, hiding microphones in flower vases, lamps, and even actors' costumes. The film included several sequences in early two-strip Technicolor, which required different lighting techniques and special camera equipment. The visual style successfully captured the glamour of the Ziegfeld Follies with elaborate costumes and sets that translated theatrical spectacle to the screen. Howe's lighting techniques evolved during production as he learned to work with both the sound equipment and the color processes, resulting in increasingly sophisticated visual storytelling as the film progressed.

Innovations

The film was notable for its early use of synchronized sound and music, representing the cutting edge of film technology in 1929. Paramount utilized the Vitaphone sound-on-disc system, which provided better audio quality than early sound-on-film processes but required precise synchronization between film and audio discs during projection. The inclusion of Technicolor sequences demonstrated Paramount's investment in new technologies, though the two-strip process could only reproduce reds and greens. The live recording of musical numbers with full orchestra was technically ambitious for the period, requiring innovative sound mixing techniques. The film also experimented with early sound dubbing and post-production audio enhancement to improve vocal clarity. The production team developed new methods for hiding microphones and managing sound reflections on set, solutions that would become standard practice in the industry.

Music

The film featured a sophisticated mix of original compositions and popular tunes of the era, including 'I'm Bringing Home a Baby Bumblebee,' 'If You Knew Susie,' and the controversial 'Makin' Whoopee.' The musical numbers were staged by Busby Berkeley in one of his earliest film assignments before he became famous for his elaborate choreography patterns. The score was composed by John Leipold and Herbert Stothart, with arrangements that showcased the capabilities of early sound recording technology. Helen Morgan performed her signature torch songs, bringing her distinctive emotional style from the Broadway stage to the screen. The soundtrack was notable for its use of leitmotifs and thematic development, techniques that were still relatively new to film scoring. The recording process was challenging, as the orchestra had to be balanced with the singers' microphones, requiring multiple takes and careful sound mixing on the set.

Famous Quotes

I'd rather be a star in the Follies than a queen anywhere else! - Barbara

Talent isn't everything in this business, kid. You need to know the right people and play the right games. - Patch Gallagher

I've been waiting for you all my life, Barbara. Can't you see that? - Bill

The stage is a cruel mistress, but she's the only one I've ever loved. - Helen Morgan (as herself)

Every girl in America dreams of being on that stage, but only a few have the courage to pay the price. - Ziegfeld representative

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence in the department store sheet music department where Barbara sings to customers while demonstrating the latest hits

- The elaborate Ziegfeld Follies production number with dozens of showgirls in spectacular costumes performing 'The American Girl'

- Helen Morgan's emotional performance of her signature torch song, captured in an intimate close-up that showcased her unique style

- The tense confrontation scene where Barbara refuses to compromise her values for stardom, standing up to Patch Gallagher's demands

- The final triumphant performance when Barbara achieves her dream, surrounded by the full spectacle of the Follies

- The Technicolor sequence featuring a lavish musical number with the entire cast in vibrant costumes

Did You Know?

- The film featured actual Ziegfeld Follies performers and was produced with full cooperation from Florenz Ziegfeld himself, who served as a technical advisor.

- Helen Morgan, who played herself in the film, was one of the most famous Broadway stars of the 1920s, known for her emotional torch songs and performances in 'Show Boat'.

- Eddie Cantor was already a major vaudeville and radio star when he appeared in this film, commanding one of the highest salaries in Hollywood at the time.

- The film featured sequences in early two-strip Technicolor, though most of it was filmed in black and white, making it one of the early films to use color technology.

- Mary Eaton, the lead actress, was a real Ziegfeld Follies performer and sister to fellow performers Doris Eaton and Pearl Eaton, all famous Broadway dancers.

- Several of the musical numbers were filmed live with the orchestra playing on set, a rare and technically difficult practice in early sound films.

- The film included a recreation of actual Ziegfeld Follies production numbers with dozens of showgirls, authentic costumes, and elaborate sets.

- The department store scenes were filmed in an actual New York department store after hours to achieve authenticity.

- This was one of the first films to feature a full orchestral score synchronized with the action throughout, rather than just during musical numbers.

- The film's title was a reference to the cultural phenomenon of the 'American Girl' archetype that was popular in 1920s media and entertainment.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film's musical numbers and the authentic performances of its Broadway stars, particularly Helen Morgan's emotional torch song performances. Variety noted the 'excellent synchronization of sound and picture' and called it 'one of the better musical productions to date.' The New York Times appreciated the film's 'genuine theatrical atmosphere' but found the plot 'somewhat conventional.' Modern film historians view the movie as an important artifact of the early sound era, valuable for its documentation of Ziegfeld Follies style and its representation of the technical challenges and artistic solutions of the transition period. Critics today recognize it as a significant stepping stone in the evolution of the Hollywood musical, though acknowledging that it lacks the narrative sophistication of later musical films.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1929 were generally enthusiastic about the film's musical sequences and the opportunity to see popular Broadway performers like Helen Morgan and Eddie Cantor on screen. The novelty of sound musicals was still fresh, and films like this one drew crowds eager to experience the new technology and see theatrical spectacles they might not have been able to attend in person. However, the film's commercial performance was moderate compared to other musicals of the period like 'The Broadway Melody,' possibly due to Mary Eaton's relatively unknown status compared to established film stars. The film found particular success in urban areas where audiences were familiar with the Ziegfeld Follies and Broadway culture. Despite not being a blockbuster, it performed well enough to justify Paramount's continued investment in musical productions during this transitional period.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The Jazz Singer (1927)

- The Broadway Melody (1929)

- Real Ziegfeld Follies productions

- Vaudeville and Broadway theatrical traditions

- Backstage drama conventions from theater

This Film Influenced

- 42nd Street (1933)

- The Great Ziegfeld (1936)

- Stage Door (1937)

- Later backstage musicals of the 1930s

- Hollywood's show business genre films

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in its complete form and has been preserved by major film archives including the Library of Congress and the UCLA Film and Television Archive. Some of the Technicolor sequences exist only in black and white copies, as the original color elements have deteriorated over time. The film underwent restoration in the 1990s as part of a project to preserve early sound musicals. The Vitaphone sound discs have been digitized and synchronized with the picture elements. While not considered a lost film, some of the original camera negative has suffered from nitrate decomposition, making preservation efforts ongoing. The restored version has been screened at classic film festivals and is available through archival channels.