Intolerance: Love's Struggle Throughout the Ages

"A Sun-Play of the Ages: A Dramatic Spectacle of Love and Intolerance Through the Centuries"

Plot

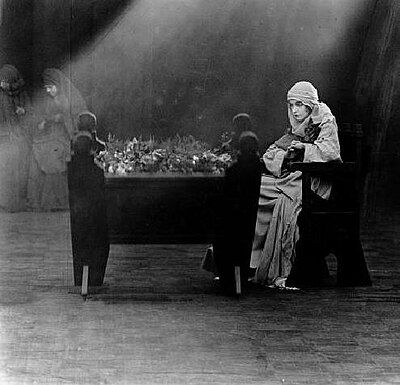

D.W. Griffith's ambitious epic interweaves four parallel stories from different historical periods, all demonstrating humanity's struggle against intolerance. In modern America (1914), a poor young couple (The Dear One and The Boy) are torn apart by social reformers and false accusations, leading to tragedy. Ancient Babylon (539 BC) shows the fall of the great city to Persian invaders amid religious conflict between Prince Belshazzar and the rival High Priest. Judea (27 AD) depicts the Pharisees' intolerance toward Jesus Christ and his followers, culminating in the crucifixion. The French Renaissance (1572) portrays the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre, where Catholic persecution of Huguenots destroys the romance between Brown Eyes and Prosper Latour. These stories are connected through the recurring motif of a mother rocking a cradle, symbolizing the eternal struggle between love and hatred throughout human history.

About the Production

The production spanned over two years (1914-1916) with massive sets including the 300-foot-high Babylonian wall. Griffith employed thousands of extras and pioneered techniques like parallel editing, crane shots, and deep focus. The film's unprecedented scale required multiple camera crews working simultaneously on different storylines. Griffith mortgaged his home to finance portions of the production after studio support waned.

Historical Background

Released during World War I, 'Intolerance' reflected the global turmoil and social upheaval of its time. The film emerged during the Progressive Era in America, a period of social reform and moral crusades that Griffith critiqued through the modern storyline. The early 1910s saw massive immigration to America, rising labor movements, and women's suffrage campaigns, all contributing to social tensions. The film's creation was directly influenced by the controversy surrounding 'The Birth of a Nation' and the growing civil rights movement. Internationally, the world was witnessing unprecedented destruction during WWI, making Griffith's message about the destructive nature of intolerance particularly resonant. The film also coincided with the early days of Hollywood's transformation into the global film capital.

Why This Film Matters

'Intolerance' revolutionized cinematic language through its pioneering use of cross-cutting between different time periods, establishing techniques that would become fundamental to film editing. Its ambitious scale set new standards for film production, proving that cinema could handle complex, epic narratives comparable to literature or opera. The film influenced countless directors including Sergei Eisenstein, who praised its editing techniques, and modern filmmakers like Francis Ford Coppola and Martin Scorsese. Its visual innovations influenced the development of film grammar, particularly in how time and space could be manipulated through editing. The film stands as a landmark of cinematic artistry, demonstrating that silent film could convey complex themes and emotions without dialogue. Its message about prejudice and intolerance remains relevant, with the film still being studied and referenced in discussions about social justice and media representation.

Making Of

The making of 'Intolerance' was one of the most ambitious and challenging productions of early cinema. Griffith worked with multiple cinematographers including G.W. Bitzer and Billy Bitzer, developing new techniques for large-scale scenes. The Babylonian set, designed by Walter L. Hall, was the largest film set ever constructed at that time, featuring massive walls and intricate details. Production was chaotic with Griffith often directing multiple scenes simultaneously across different sets. The famous battle sequence required careful choreography of thousands of extras, horses, and chariots. Many cast and crew members suffered injuries during the demanding production. Griffith's perfectionism led to constant reshoots and improvisation, often changing scenes based on his daily inspirations. The film's complex editing required months of work to properly interweave the four storylines.

Visual Style

The cinematography, primarily by G.W. Bitzer and Billy Bitzer, was groundbreaking for its time. The film featured innovative camera movements including the famous crane shot descending from the Babylonian walls, one of the first uses of a camera crane in cinema. The cinematographers employed deep focus techniques to capture massive sets with thousands of extras in sharp detail. They developed new lighting techniques to create dramatic shadows and highlights, particularly in the modern story sequences. The battle scenes featured dynamic tracking shots and multiple camera angles to capture the scale of the action. The visual style varied between the four stories, with each period receiving distinct photographic treatment - Babylon was grand and spectacular, Judea was stark and spiritual, Renaissance France was rich and textured, and modern America was gritty and realistic. The film's visual language established conventions that would influence cinematography for decades.

Innovations

'Intolerance' pioneered numerous technical innovations that would become standard in filmmaking. The film's parallel editing between four different time periods was revolutionary, establishing cross-cutting as a fundamental cinematic technique. The production featured the first use of a camera crane for the dramatic descending shot in Babylon. Griffith developed techniques for managing thousands of extras in complex battle sequences, including detailed storyboards and rehearsal systems. The film's massive sets required new construction techniques and engineering innovations. The editing process, which took months, involved synchronizing four different storylines with different pacing and visual styles. The production also experimented with color tinting, using different color schemes for each time period. The film's length required new projection technology and theater accommodations. These technical achievements pushed the boundaries of what was possible in cinema and established many conventions still used in filmmaking today.

Music

The original score was composed by Joseph Carl Breil, who had also scored 'The Birth of a Nation.' The music was designed to enhance the emotional impact of each storyline while providing continuity between the different time periods. Breil incorporated classical themes and original compositions, using leitmotifs to connect characters and themes across the four stories. The score was performed live in theaters by orchestras during initial screenings, with cue sheets provided to synchronize the music with the action. Modern restorations have featured newly composed scores by contemporary composers including Carl Davis and the Mont Alto Motion Picture Orchestra. The music plays a crucial role in unifying the film's complex structure, with recurring themes helping audiences follow the parallel narratives. The soundtrack's emotional power compensates for the lack of dialogue, with the music conveying the film's themes of love, suffering, and redemption.

Famous Quotes

The story of a dear one... and a boy... and the love that would not die.

Out of the cradle, endlessly rocking.

When women cease to attract men, they will turn to spiritualism and spiritualism will become a fad.

The little girl who was dear to us all, whose heart was as pure as the morning dew.

In each age, the same story repeats itself: love struggling against intolerance.

The boy was a good boy. He had his faults, but he was good at heart.

Memorable Scenes

- The massive Babylonian battle sequence with thousands of extras, chariots, and elephants storming the city walls

- The iconic crane shot descending from the top of the Babylonian set to the street level below

- The heartbreaking scene where The Dear One has her baby taken away by social reformers

- The crucifixion sequence in Judea, filmed with spiritual reverence and visual poetry

- The final montage rapidly cutting between all four stories as the modern couple faces execution

- The St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre scene showing the brutal persecution of Huguenots

- The recurring motif of the mother rocking the cradle, connecting all four storylines

- The Babylonian feast scene with its opulent sets and thousands of extras

Did You Know?

- The Babylonian set was so massive and impressive that it became a Hollywood landmark for years after filming, used in numerous other films before being demolished in 1924

- Griffith created the film partly as a response to criticism he received for 'The Birth of a Nation' (1915), which was accused of promoting racism

- The film's original title was 'The Mother and the Law,' with the modern story being the primary focus before Griffith expanded it into the epic format

- Over 60,000 people were employed during the production, including thousands of extras for the battle scenes

- The famous crane shot that descends from the Babylonian set to street level was one of the first uses of a camera crane in cinema history

- Griffith reportedly screened rushes for audiences during production to gauge reactions and adjust the film accordingly

- The film's failure financially nearly bankrupted Triangle Film Corporation and Griffith personally

- The intercutting technique between four different time periods was revolutionary and influenced countless future filmmakers

- The character 'The Dear One' was played by Mae Marsh, who had to perform difficult scenes including having her baby taken away and facing execution

- Griffith spent $50,000 (equivalent to over $1.3 million today) just on costumes for the Babylonian sequences

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception was mixed to positive, with many critics acknowledging the film's technical brilliance while questioning its narrative complexity. The New York Times praised its 'magnificent spectacle' but found the intercutting confusing. Variety called it 'the greatest picture ever made' despite its commercial failure. Modern critics universally acclaim it as a masterpiece; Roger Ebert included it in his Great Movies collection, calling it 'perhaps the most ambitious film ever made.' Sight & Sound ranked it among the greatest films of all time in multiple polls. Film scholars consider it a crucial text in understanding the development of cinematic language, with particular praise for its editing innovations and visual storytelling. The film's reputation has grown significantly over time, with many now considering it superior to 'The Birth of a Nation' in both artistic merit and social consciousness.

What Audiences Thought

Initial audience reception was disappointing, with many viewers finding the film's complex narrative structure confusing and its length excessive. The film's commercial failure shocked the industry, given Griffith's previous success with 'The Birth of a Nation.' Contemporary audiences were divided, with some praising its spectacle while others criticized its perceived moralizing. Over time, audience appreciation has grown significantly, particularly among film enthusiasts and scholars. Modern audiences often find the film surprisingly accessible despite its age, thanks to its visual storytelling and emotional power. The film has developed a cult following among cinema lovers and is frequently screened at film festivals and repertory theaters. Its restoration and availability on home video have introduced it to new generations, who often express amazement at its technical achievements and emotional impact.

Awards & Recognition

- Preserved in the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress (1989)

- Ranked #49 in the American Film Institute's 100 Greatest American Films (1998)

- Voted one of the Top 100 Films by the Village Voice (1999)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- 'The Birth of a Nation' (1915) - as a response to criticism

- Thomas Dixon Jr.'s novels - for themes of social conflict

- Classical literature and epic poetry - for narrative structure

- Biblical stories - particularly for the Judea sequence

- Historical texts about Babylon and French religious wars

- Contemporary social reform movements - as critique

- Griffith's own short films - for technical experimentation

This Film Influenced

- 'Battleship Potemkin' (1925) - Eisenstein's editing techniques

- 'Metropolis' (1927) - for epic scale and social themes

- 'The Ten Commandments' (1956) - for biblical epic style

- 'Ben-Hur' (1959) - for historical spectacle

- 'Once Upon a Time in America' (1984) - for parallel narrative structure

- 'The Godfather Part II' (1974) - for cross-cutting between time periods

- 'Pulp Fiction' (1994) - for non-linear storytelling

- 'Cloud Atlas' (2012) - for multiple interconnected stories across time

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved by the Museum of Modern Art and the Library of Congress. Multiple versions exist due to Griffith's re-editing over the years. The most complete restoration was undertaken by Kevin Brownlow and David Gill in the 1980s, combining footage from various archives worldwide. The film was selected for preservation in the National Film Registry in 1989 for its cultural, historical, and aesthetic significance. Digital restorations have been completed, with the most recent being a 4K restoration by Cohen Film Collection. Some footage remains lost, particularly from the modern story sequences, but the film survives in a remarkably complete state considering its age.