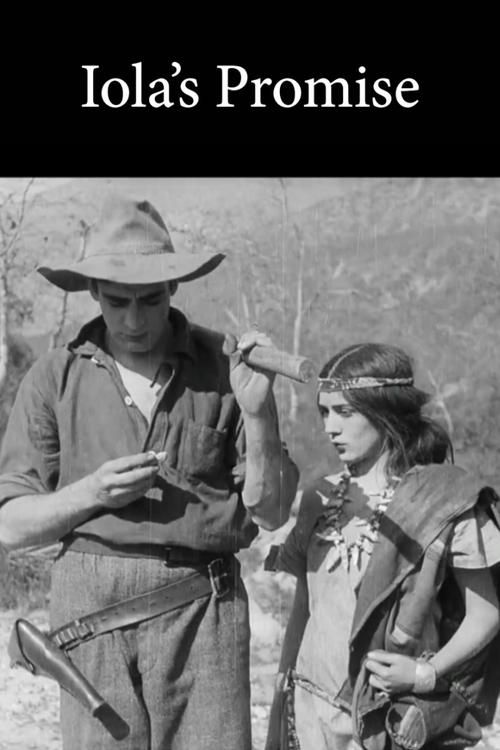

Iola's Promise

"A Story of the Red Man's Gratitude"

Plot

Iola, a young Native American girl, is rescued from captivity by Jack Harper, a prospector who differs from the other white men she has encountered. When Jack reveals his financial struggles to find gold, Iola earnestly promises to help him succeed. Confused by Jack's 'cross your heart' gesture, she interprets it as a tribal insignia and tells her people that 'Crossheart' individuals are trustworthy. True to her word, Iola leads Jack to a valuable gold discovery, but her ultimate act of gratitude comes when she sacrifices her own life to protect Jack's sweetheart from an attack by her own tribe, demonstrating profound loyalty and transcending cultural barriers.

About the Production

Filmed during Griffith's prolific period at Biograph where he directed dozens of short films annually. The production utilized authentic-looking Native American costumes and props typical of the era. The wagon train scenes were likely filmed on location using actual covered wagons. The cross-your-heart gesture became a central visual motif that Griffith used to bridge cultural understanding between characters.

Historical Background

1912 was a pivotal year in American cinema, marking the transition from short films to feature-length productions. The film industry was rapidly consolidating in California, with Hollywood emerging as the center of American filmmaking. D.W. Griffith was at Biograph Studios, creating the foundational techniques of narrative cinema that would influence generations of filmmakers. This period saw the rise of the star system, with actors like Mary Pickford becoming recognizable personalities that audiences specifically sought out. The film was released during the Progressive Era, a time of social reform and changing attitudes toward race and immigration in America, though these changes were reflected through the limited perspectives of the time. The Western genre was particularly popular, reflecting America's ongoing fascination with frontier mythology and the closing of the American West.

Why This Film Matters

Iola's Promise represents an early example of the sympathetic Native American character in American cinema, though filtered through the paternalistic and stereotypical lens of 1912. The film contributed to the development of the Western genre's narrative conventions, particularly the themes of cultural understanding and sacrifice across racial divides. Mary Pickford's performance helped solidify her image as America's Sweetheart, a persona that would make her one of the most powerful women in early Hollywood. The film's exploration of cross-cultural communication, despite its limitations, was relatively progressive for its time in suggesting that understanding could bridge racial divides. As part of Griffith's extensive Biograph output, it represents a step in the director's development toward more ambitious and controversial works that would shape American cinema.

Making Of

The film was made during D.W. Griffith's incredibly productive period at Biograph Studios, where he was essentially creating the language of cinema through experimentation with cross-cutting, camera movement, and narrative structure. Mary Pickford, who would later co-found United Artists and become one of the most powerful women in Hollywood, was still developing her screen persona. The production would have been remarkably efficient by modern standards, with Griffith often shooting multiple films simultaneously using the same locations and crew members. The Native American themes, while problematic by today's standards, were part of Griffith's broader interest in exploring American identity and cultural conflicts through cinema. The film's emotional climax, involving Iola's sacrifice, demonstrates Griffith's early mastery of melodramatic storytelling techniques that would become his trademark.

Visual Style

The cinematography, likely handled by Billy Bitzer or G.W. Bitzer (Griffith's regular cameraman), employed the natural lighting techniques typical of Biograph productions. The film used location photography for the Western scenes, taking advantage of California's varied landscapes. The camera work was relatively static by modern standards but included some movement and varied angles that were innovative for the period. The wagon train sequences would have required careful composition to convey the scale and movement of the caravan. The visual storytelling relied on close-ups for emotional moments, particularly in scenes involving Iola's promises and sacrifices, demonstrating Griffith's pioneering use of intimate shots to convey character emotions.

Innovations

While not as technically innovative as some of Griffith's other works from this period, the film demonstrates his mastery of narrative pacing within the constraints of a single reel. The cross-cutting between different character perspectives and the use of the cross-your-heart gesture as a visual motif show Griffith's developing cinematic language. The film's efficient storytelling, conveying a complete emotional arc in approximately ten minutes, represents the technical skill required for successful one-reel productions. The location filming and coordination of wagon train sequences required logistical expertise that was becoming increasingly sophisticated in 1912.

Music

As a silent film, Iola's Promise would have been accompanied by live musical performance in theaters. The typical accompaniment would have included a piano or small orchestra playing appropriate mood music. For the Western setting, theaters likely used popular American folk tunes, classical pieces with appropriate emotional tone, and specially composed cues. The cross-your-heart scene might have featured lighter, more playful music to emphasize the cultural misunderstanding, while the sacrifice sequence would have been accompanied by dramatic, emotional music to heighten the impact. No original score survives, as was common for films of this era.

Famous Quotes

Will you? Yes. Cross your heart?

Crossheart people are all right

I will help you find gold

Iola surely pays her debt of gratitude

Memorable Scenes

- The moment Iola misunderstands the 'cross your heart' gesture and adopts it as a tribal symbol

- Iola's emotional promise to help Jack find gold

- The climactic sacrifice scene where Iola protects Jack's sweetheart at the cost of her own life

- The initial rescue of Iola from the cutthroats

- The discovery of gold that fulfills Iola's promise

Did You Know?

- This was one of over 150 short films D.W. Griffith directed in 1912 alone during his Biograph period

- Mary Pickford, though already a rising star, was still working in short films before becoming one of the highest-paid actresses in Hollywood

- The film was released just months before Griffith would begin work on his controversial but technically groundbreaking feature 'The Birth of a Nation'

- The 'cross your heart' misunderstanding was a clever narrative device that Griffith used to explore cultural differences in a way audiences of 1912 could understand

- Alfred Paget was a British actor who frequently appeared in Griffith's Biograph films before returning to England in 1913

- The film represents an early example of Griffith's interest in racial themes, though through the problematic lens of early 20th century stereotypes

- Like many Biograph films of this era, it was likely shot in just one or two days

- The wagon train sequences may have utilized the same locations and props Griffith used in other Western-themed Biograph shorts

- This film was part of Biograph's strategy to release multiple films weekly to meet the growing demand for motion pictures

- The preservation of this film is notable given that approximately 90% of American silent films have been lost

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews in trade publications like The Moving Picture World and Variety noted the film's emotional power and Mary Pickford's appealing performance. Critics of the time praised Griffith's ability to create compelling narratives within the constraints of a single reel. Modern film historians view the film as a representative example of Griffith's Biograph period, noting his developing directorial style and the early emergence of themes he would explore more fully in later works. While the racial stereotypes are criticized by contemporary scholars, the film is acknowledged for its attempt at creating a sympathetic Native American character, which was relatively uncommon for the period.

What Audiences Thought

The film was well-received by audiences of 1912, who were particularly drawn to Mary Pickford's performances and Griffith's emotionally resonant storytelling. The themes of loyalty, sacrifice, and cross-cultural understanding resonated with contemporary audiences, and the film's melodramatic elements were in line with popular tastes of the silent era. Audiences would have appreciated the clear moral framework and emotional payoff, which were hallmarks of Griffith's most successful Biograph productions. The film likely performed well in the rental market, as most Biograph films of this period did, contributing to the studio's commercial success.

Awards & Recognition

- None (Academy Awards were not established until 1929)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Contemporary dime novels about the American West

- Stage melodramas

- Earlier Biograph Western shorts

- James Fenimore Cooper's frontier narratives

This Film Influenced

- Later Griffith films dealing with racial themes

- Subsequent Biograph Western productions

- Early Hollywood Westerns featuring sympathetic Native American characters

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Preserved - The film survives in the film archives and has been made available through various film preservation organizations. It is part of the collection of early American cinema preserved by institutions like the Museum of Modern Art and the Library of Congress.