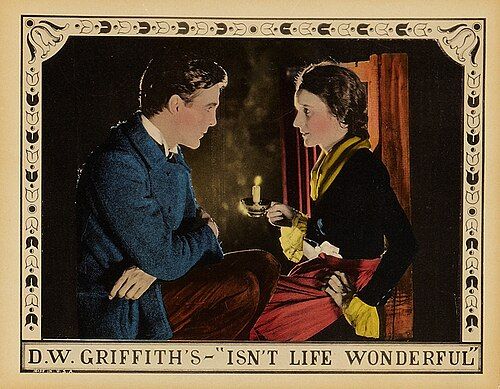

Isn't Life Wonderful

"A Story of Love and Courage in the Ruins of War"

Plot

In post-World War I Germany, a Polish family struggles to survive amid the devastating economic conditions of the Great Inflation. The story centers on Inga, a Polish war orphan who has saved a small fortune from scavenging in the rubble, and her dreams of marrying Paul, a former soldier weakened by poison gas exposure. Paul, serving as the family's symbol of hope and optimism, invests his remaining strength and resources in securing Inga's future despite their overwhelming poverty. As inflation spirals out of control, the family faces mounting challenges including food shortages, housing crises, and the constant threat of starvation. Their resilience is tested when Paul's health deteriorates and their savings become nearly worthless, forcing them to rely on their love and determination to survive. The film culminates in a poignant exploration of human endurance and the power of hope in the face of seemingly insurmountable adversity.

About the Production

Griffith invested significant personal funds into this production, believing in its social importance. The film was shot during a period when Griffith was struggling to maintain his artistic independence in the face of changing Hollywood economics. The production used authentic European footage and detailed set designs to recreate post-war Germany's devastated landscape.

Historical Background

The film was produced during a critical period in world history, just after the hyperinflation crisis that devastated Germany in 1923. The Weimar Republic was struggling to stabilize its economy while dealing with the aftermath of World War I, including massive war reparations imposed by the Treaty of Versailles. In the United States, the Roaring Twenties were in full swing, creating a stark contrast with the European devastation depicted in the film. This period also marked a transition in Hollywood from the artistic experimentation of the early 1920s to the more commercially-driven studio system that would dominate the rest of the decade. Griffith's own career was at a crossroads, as his influence waned and newer directors like Chaplin and Keaton gained popularity. The film's release coincided with growing American isolationism and a desire to forget European problems, which may have contributed to its poor reception.

Why This Film Matters

'Isn't Life Wonderful' represents one of Hollywood's earliest attempts to address the European post-war experience with empathy and authenticity. Unlike many contemporary films that portrayed Germans as villains, Griffith's work humanized the suffering of ordinary people caught in economic catastrophe. The film's detailed depiction of hyperinflation's effects on daily life - from wheelbarrows full of worthless money to the desperation for basic necessities - provided American audiences with a rare glimpse into European reality. While commercially unsuccessful, the film influenced later socially conscious cinema and demonstrated Griffith's continued commitment to using film as a medium for social commentary. Its failure also marked a turning point in Hollywood's approach to serious European subjects, leading studios to favor more escapist fare throughout the remainder of the decade.

Making Of

The production of 'Isn't Life Wonderful' reflected D.W. Griffith's commitment to socially relevant cinema during a period when audiences increasingly preferred light entertainment. Griffith, still riding the controversy of his earlier works like 'The Birth of a Nation' and 'Intolerance', chose this material as an attempt to address contemporary European issues with empathy and nuance. The casting of Carol Dempster, with whom Griffith had a personal relationship, was controversial even at the time, as many critics felt her performance lacked the depth required for such a serious role. Griffith spared no expense in creating authentic sets and procuring actual European footage to establish the film's realistic tone. The production faced numerous challenges including the need to recreate the specific atmosphere of post-war Germany and the Great Inflation period, which required extensive research and consultation with European refugees. Griffith's meticulous attention to detail extended to every aspect of production, from costume design to the authentic recreation of Berlin's streets during the inflation crisis.

Visual Style

The cinematography, handled by Hendrik Sartov and Billy Bitzer, employed Griffith's characteristic use of close-ups and cross-cutting to build emotional intensity. The film featured remarkable location footage of post-war Europe, blended seamlessly with studio shots to create a convincing portrait of devastated Germany. Sartov's use of soft focus lighting, particularly in scenes with Carol Dempster, created an ethereal quality that contrasted with the harsh reality of the setting. The visual style incorporated documentary-like realism in the street scenes, showing the actual conditions of the inflation crisis, while maintaining Griffith's romantic visual language in the intimate moments between the lovers. The camera work emphasized the contrast between the grand scale of economic disaster and the personal struggles of the characters.

Innovations

The film pioneered the use of authentic documentary footage integrated with narrative fiction, a technique that would become more common in later cinema. Griffith's innovative use of parallel editing to contrast personal stories with broader social conditions demonstrated his continued technical mastery. The production's detailed recreation of the German inflation crisis, including accurate depictions of worthless currency and food shortages, represented an early example of cinematic social realism. The film's lighting techniques, particularly the use of natural light in outdoor scenes, created a documentary-like authenticity that enhanced its social commentary.

Music

As a silent film, 'Isn't Life Wonderful' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The typical score would have included classical pieces adapted to suit the film's emotional tone, with popular works by composers like Chopin and Beethoven likely used for the romantic scenes. The musical accompaniment would have been particularly important in conveying the film's emotional arc, from despair to hope. Modern restorations have been scored by contemporary composers who attempt to recreate the authentic silent film experience while incorporating musical elements that reflect the film's European setting and serious themes.

Famous Quotes

In times like these, love is the only currency that never loses its value.

We may have nothing but each other, but that is everything.

Even when the world falls apart, the human heart finds reasons to hope.

In the ruins of war, we plant the seeds of tomorrow.

Money comes and goes, but love remains forever.

Memorable Scenes

- The powerful opening sequence showing actual footage of war-ravaged Europe, establishing the documentary-like authenticity that sets the tone for the entire film.

- The heartbreaking scene where Paul, weakened by poison gas, struggles to climb stairs while carrying groceries, symbolizing the physical toll of war on an entire generation.

- The iconic market scene where wheelbarrows full of worthless money are exchanged for basic food items, dramatically illustrating the hyperinflation crisis.

- The tender moment between Inga and Paul in their barren apartment, where they dance to imaginary music, demonstrating love's power to transcend material poverty.

- The final scene where the family gathers around a meager meal, their faces illuminated by candlelight, representing hope amid darkness.

Did You Know?

- This was one of D.W. Griffith's last major silent films before his career decline in the late 1920s

- Carol Dempster, who played Inga, was Griffith's protégée and romantic partner at the time

- The film was based on the short story 'Isn't Life Wonderful?' by Geoffrey Moss

- Griffith considered this one of his most personal and socially important works

- The film's depiction of German hyperinflation was remarkably accurate and timely, as Germany was experiencing its worst inflation crisis in 1923-1924

- Despite its artistic merits, the film was poorly received by audiences who preferred more escapist entertainment

- The original title was simply 'Life Wonderful' before 'Isn't' was added

- Griffith used actual European war footage in the opening sequences to establish authenticity

- Neil Hamilton, who played Paul, later became famous for playing Commissioner Gordon in the 1960s Batman TV series

- The film's failure contributed to Griffith's loss of artistic independence and his eventual departure from United Artists

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics were divided on the film's merits. While many praised Griffith's technical skill and humanitarian intentions, others found the film overly sentimental and slow-paced. The New York Times acknowledged the film's noble intentions but criticized its execution, noting that Griffith's 'heart was in the right place' but the film lacked the dramatic power of his earlier works. Modern critics have reassessed the film more favorably, recognizing it as an important social document and one of Griffith's most mature works. Film historians appreciate its authentic depiction of the German inflation crisis and its humanitarian perspective, which was unusual for American cinema of the period. The film is now regarded as an underrated masterpiece that showcases Griffith's ability to handle contemporary social issues with sensitivity and depth.

What Audiences Thought

The film was a commercial failure, reflecting audience preferences for lighter entertainment during the prosperous Roaring Twenties. American audiences, still recovering from World War I and enjoying economic boom times, showed little interest in the grim realities of European suffering. The film's serious tone and depressing subject matter contrasted sharply with the popular comedies and romances that dominated theaters in 1924. Many viewers found the film too depressing and foreign in its concerns, leading to poor box office returns despite Griffith's established reputation. The failure of this film, along with other serious works of the period, convinced Hollywood studios that audiences preferred escapism to social commentary, influencing production trends for the rest of the decade.

Awards & Recognition

- No major awards were won by this film

Film Connections

Influenced By

- German Expressionist cinema's visual style

- Contemporary European literature about the war

- Griffith's earlier social films like 'Intolerance'

- Documentary footage from post-war Europe

- Realist literary traditions of the 1920s

This Film Influenced

- The Last Laugh (1924)

- The Crowd (1928)

- Street Angel (1928)

- Heroes for Sale (1933)

- I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang (1932)

- The Grapes of Wrath (1940)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved in the Library of Congress and has been restored by several film archives. While complete prints exist, some versions show varying degrees of deterioration due to the nitrate film stock used in the 1920s. The most complete restoration was undertaken by the Museum of Modern Art in the 1990s, combining elements from multiple sources to create the most definitive version available. The film is considered at-risk but not lost, with preservation efforts ongoing to ensure its survival for future generations.