Love, Speed and Thrills

"A Keystone Comedy of Love, Speed and Thrills!"

Plot

In this classic Keystone comedy, after the character known as Walrus (Mack Swain) sustains a gunshot wound, the kind-hearted Ambrose takes him into his home to recover. However, Ambrose's hospitality turns to jealousy when he discovers Walrus attempting to flirt with his wife, prompting him to leave in anger. The situation escalates dramatically when Walrus absconds with Mrs. Ambrose, forcing Ambrose to pursue them on horseback in a desperate rescue attempt. Adding to the chaos, the bumbling Keystone Kops join the chase, creating a frantic pursuit filled with slapstick mishaps and comic misunderstandings. The film culminates in a wild chase sequence that combines physical comedy with the action elements typical of Keystone's productions.

About the Production

This film was produced during the peak of Keystone Studios' output in 1915, when the studio was releasing multiple films per week. The production likely utilized Keystone's signature fast-paced shooting schedule, with most scenes completed in one or two takes. The chase sequences would have been filmed on location around the Edendale area, taking advantage of the rural landscape that surrounded the studio at the time.

Historical Background

1915 was a transformative year in American cinema, occurring during the transitional period between the early nickelodeon era and the emergence of the feature film as the dominant format. World War I was raging in Europe, though the United States had not yet entered the conflict, and American films were beginning to dominate international markets. The film industry was consolidating in Hollywood, with Keystone Studios being one of the major players in comedy production. This period saw the rise of comedy as a commercially viable genre, with stars like Charlie Chaplin (who had left Keystone by 1915), Mabel Normand, and the Keystone ensemble creating a distinctly American style of physical comedy. The technical aspects of filmmaking were also evolving rapidly, with cameras becoming more mobile and editing techniques growing more sophisticated, allowing for the dynamic chase sequences that characterized films like this one.

Why This Film Matters

As a representative example of Keystone comedy at its peak, 'Love, Speed and Thrills' embodies the slapstick style that would influence generations of comedians and filmmakers. The film's structure—particularly its use of escalating chaos and chase sequences—became a template for physical comedy that persists in various forms today. The Keystone Kops, featured in this film, became cultural icons representing incompetent authority, a trope that has been endlessly referenced and parodied. The film also reflects the gender dynamics of early cinema, where female characters like Mrs. Ambrose (played by Minta Durfee) were often portrayed as objects of pursuit or comic misunderstanding. This style of comedy helped establish American cinema's reputation for innovation and entertainment, contributing to the global dominance of Hollywood films in subsequent decades.

Making Of

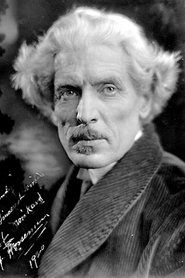

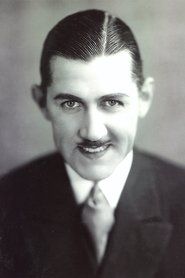

The production of 'Love, Speed and Thrills' typified the Keystone Studios approach to comedy filmmaking in 1915. Director Walter Wright, who had begun his career as an actor, understood the importance of physical comedy and timing that made Keystone films successful. The cast, led by Mack Swain (a Keystone regular since 1913), brought their established comedic personas to the production. The chase scenes would have been choreographed with minimal rehearsal, relying on the performers' improvisational skills and the spontaneity that Keystone prized. The film was likely shot in just a few days, using the studio's backlot and nearby locations in Edendale (now part of Los Angeles). The Keystone Kops, though not the central focus, would have been played by studio regulars who specialized in the chaotic, incompetent police work that made them famous.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'Love, Speed and Thrills' reflects the standard practices of Keystone Studios in 1915. The film would have been shot on 35mm film using hand-cranked cameras, allowing for variable speeds that enhanced the comic effect during chase sequences. The camera work was primarily static, following the common practice of the era, though some tracking shots may have been employed during the horse chase scenes. Natural lighting was used for exterior scenes, while interior shots would have been lit with early artificial lighting equipment. The visual style emphasized clarity and action, with wide shots preferred to capture the full range of physical comedy. The film's black and white imagery would have been tinted in some releases, with common practices including amber tints for interior scenes and blue tints for night sequences.

Innovations

While 'Love, Speed and Thrills' was not technically innovative for its time, it demonstrated the sophisticated use of established techniques that had become standard at Keystone Studios by 1915. The film's chase sequences required careful coordination between camera operators, actors, and stunt performers, showcasing the studio's mastery of complex action scenes. The editing, while simple by modern standards, effectively built tension and comic timing through the juxtaposition of different shots and perspectives. The production also utilized location shooting effectively, taking advantage of the varied landscapes around Los Angeles to create dynamic visual interest. The film represents the refinement of the comedy short format, with its efficient storytelling and maximum use of its brief runtime to deliver entertainment value.

Music

As a silent film, 'Love, Speed and Thrills' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its theatrical run. The typical accompaniment would have consisted of a pianist in smaller theaters or a small orchestra in larger venues. The music would have been compiled from popular pieces of the era, with selections chosen to match the mood of each scene—lively, upbeat music for chase sequences, romantic themes for the scenes between characters, and dramatic music for moments of tension. Some theaters may have used cue sheets provided by the studio or by music publishers, which suggested appropriate musical selections for different types of scenes. The score would have been largely improvisational, with musicians adapting their performance to audience reactions and the specific needs of each screening.

Memorable Scenes

- The climactic horse chase sequence featuring Ambrose pursuing Walrus and Mrs. Ambrose while the Keystone Kops create additional chaos with their bumbling attempts to capture Walrus, combining multiple forms of transportation and physical comedy in a rapid succession of gags and near-misses.

Did You Know?

- This film was part of Keystone's prolific 1915 output, when the studio was producing hundreds of short comedies annually

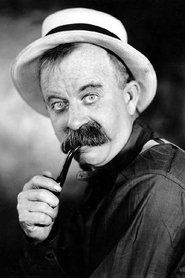

- Mack Swain's character 'Walrus' was a recurring persona in Keystone comedies, known for his distinctive walrus mustache

- Chester Conklin, another Keystone regular, often appeared alongside Swain in comedy pairings

- The film was released just as Mack Sennett was transitioning Keystone to feature-length productions

- Keystone Kops appeared in dozens of films during this period, becoming one of the most recognizable comedy tropes of the silent era

- Director Walter Wright was a former actor who transitioned to directing at Keystone

- The film's title reflects the common practice of using attention-grabbing, action-oriented titles for comedy shorts

- 1915 was a pivotal year for comedy films, with Chaplin's emergence as a star changing the landscape of the genre

- The horse chase sequence would have been considered relatively ambitious for a short comedy of this period

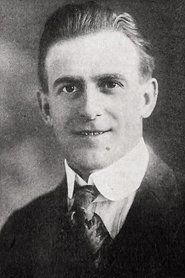

- Minta Durfee was married to Roscoe 'Fatty' Arbuckle during this time, though they would separate in 1925

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews of 'Love, Speed and Thrills' are scarce, as most film trade publications of 1915 focused more on major releases than on short comedies. However, Keystone films of this period were generally received positively by audiences and reviewers who appreciated their energetic pace and physical comedy. The Moving Picture World, a leading trade publication of the era, typically praised Keystone productions for their entertainment value and crowd-pleasing qualities. Modern film historians view this film as a representative example of the Keystone style, noting its importance in the development of American comedy cinema, though it's not considered among the studio's most groundbreaking works.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1915 responded enthusiastically to Keystone comedies like 'Love, Speed and Thrills,' which were designed to provide quick, accessible entertainment to theatergoers. The film's combination of romance, action, and comedy appealed to the broad audiences that frequented nickelodeons and small theaters. The recognizable cast members—particularly Mack Swain and the Keystone Kops—would have been draws for regular moviegoers who followed their favorite comedy stars. The fast-paced chase sequences and physical humor were particularly effective in holding audience attention during an era when films competed with vaudeville and other live entertainments. The film likely played well in both urban and rural markets, as its visual comedy transcended language and cultural barriers.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Earlier Keystone comedies

- French and Italian slapstick films

- Vaudeville comedy routines

- Mack Sennett's established comedy formula

This Film Influenced

- Later Keystone comedy shorts

- Chase sequences in subsequent comedy films

- Police comedy films

- Slapstick comedies of the 1920s

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The preservation status of 'Love, Speed and Thrills' is uncertain, as many Keystone shorts from this period have been lost. Some Keystone films survive in archives such as the Library of Congress, the Museum of Modern Art, and the UCLA Film & Television Archive, but others exist only in fragmentary form or are considered lost. The film may survive in private collections or European archives where Keystone films were distributed. No comprehensive restoration of this specific title is currently documented.