Madame DuBarry

"The Greatest Love Story of the French Court!"

Plot

The film follows Jeanne Bécu, a beautiful working-class girl in 18th-century Paris who rises from humble beginnings as a milliner's assistant to become the last official mistress of King Louis XV. After catching the king's eye through her charm and beauty, she is installed at Versailles as Madame Du Barry, where she faces fierce opposition from the aristocratic court, particularly from the king's daughters and the future King Louis XVI. Despite the political intrigues and isolation at court, she finds genuine love with a young nobleman, Armand de Foix, creating a dangerous love triangle. As the French Revolution begins to brew, her position becomes increasingly precarious, and she ultimately faces the guillotine in 1793, meeting her fate with courage and dignity. The film chronicles her dramatic journey from the heights of royal favor to the depths of revolutionary terror, exploring themes of love, power, and the inevitable fall of the aristocracy.

About the Production

The film featured extraordinarily elaborate sets and costumes, with the court scenes requiring hundreds of extras. The production was so ambitious that it took nearly six months to complete, an unusually long period for films of the era. The guillotine scene was particularly controversial for its graphic depiction. Lubitsch insisted on historical accuracy in costumes and set design, consulting historical experts to recreate Versailles authentically.

Historical Background

The film was produced during a critical period in German history, immediately following World War I and during the turbulent Weimar Republic era. The German film industry, particularly through UFA, was making a concerted effort to compete with Hollywood by producing high-quality, internationally appealing films. This period saw German cinema achieve unprecedented artistic and technical sophistication, with directors like Lubitsch, Murnau, and Lang creating works that would influence cinema worldwide. The choice of a French historical subject was strategic, allowing German filmmakers to demonstrate their capability to produce international epics while avoiding contemporary German themes that might be politically sensitive. The film's success represented a cultural victory for Germany at a time when the country was economically devastated but artistically flourishing.

Why This Film Matters

'Madame DuBarry' represents a pivotal moment in cinema history, marking the transition from simple melodramas to sophisticated historical epics. The film established Pola Negri as the first European star to achieve major success in Hollywood, paving the way for other European actors like Greta Garbo and Marlene Dietrich. Ernst Lubitsch's direction introduced a subtle, sophisticated approach to storytelling that would become known as the 'Lubitsch Touch,' influencing generations of filmmakers. The film demonstrated that historical dramas could be both commercially successful and artistically ambitious, leading to a golden age of historical epics in the 1920s. Its international success helped establish the global film market as we know it today, proving that films could cross cultural and language barriers. The film also contributed to the development of costume design as a crucial element of filmmaking, with its authentic 18th-century wardrobes setting new standards for period productions.

Making Of

The production of 'Madame DuBarry' was a monumental undertaking for post-WWI German cinema. Director Ernst Lubitsch, then only 26 years old, demonstrated extraordinary ambition in recreating the splendor of 18th-century Versailles on studio sets. The relationship between Lubitsch and star Pola Negri during filming was intense and complicated, with both professional collaboration and romantic involvement. Emil Jannings, who played King Louis XV, was known for his method approach to acting and reportedly stayed in character throughout the entire shoot. The production employed hundreds of craftsmen to create the elaborate costumes and sets, with some costumes requiring months of work by specialized tailors and embroiderers. The film's most challenging sequence was the revolutionary mob scene, which required coordinating hundreds of extras while maintaining period authenticity. Lubitsch's attention to detail extended to requiring that all background actors learn proper 18th-century court etiquette and mannerisms.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Theodor Sparkuhl was revolutionary for its time, employing innovative lighting techniques to create dramatic depth and atmosphere. The film used sophisticated camera movements, including tracking shots that followed characters through the elaborate palace sets. The lighting design was particularly noteworthy, with Sparkuhl using chiaroscuro effects to enhance the emotional intensity of key scenes. The film employed multiple camera setups for complex scenes, a technique that was still relatively rare in 1919. The cinematography successfully balanced the need to showcase the spectacular sets with intimate character moments, using varying focal lengths to achieve both effects. The color tinting of different scenes (amber for daylight, blue for night, red for dramatic moments) added emotional depth to the black and white photography.

Innovations

The film pioneered several technical innovations that would become standard in later historical epics. The production developed new techniques for creating realistic period costumes that allowed for freedom of movement while maintaining historical accuracy. The set design introduced modular construction methods that allowed for quick changes between different palace locations. The film employed early forms of matte painting to extend the apparent size of the Versailles sets. The guillotine sequence featured innovative special effects that created a convincing illusion of the execution without actual danger to the performer. The production also developed new lighting equipment that could be hidden within the elaborate sets to create more naturalistic lighting while maintaining the period aesthetic.

Music

As a silent film, 'Madame DuBarry' was originally accompanied by a full orchestral score composed by Giuseppe Becce. The score incorporated period-appropriate music, including adaptations of 18th-century French compositions and original pieces that reflected the film's dramatic arc. Different theaters used various approaches to musical accompaniment, ranging from full orchestras in prestigious cinemas to single pianists in smaller venues. The music was carefully synchronized with the on-screen action, with specific leitmotifs for main characters and emotional themes. The score emphasized the contrast between the opulence of court life and the terror of the revolution, using musical styles to reinforce these opposing worlds.

Famous Quotes

"I would rather die on the scaffold than live without love." - Madame Du Barry

"The king's favor is as fleeting as spring flowers." - Court Advisor

"Revolution comes not from the poor, but from the hearts of those who have known injustice." - Armand de Foix

"Even queens must bow before the guillotine." - Revolutionary Leader

Memorable Scenes

- The grand entrance of Madame Du Barry at Versailles, with her descending a magnificent staircase in an elaborate gown while the court watches in stunned silence

- The intimate balcony scene where Du Barry and Armand declare their love while fireworks illuminate the night sky over Paris

- The tense confrontation scene between Du Barry and the future Louis XVI, where political tensions and personal animosities explode

- The revolutionary mob storming the palace, with chaos and destruction captured in sweeping camera movements

- The final guillotine sequence, filmed with stark realism and emotional intensity, showing Du Barry's courage in facing death

Did You Know?

- This was the film that launched Pola Negri's international career and led to her contract with Paramount Pictures in 1922

- Emil Jannings' portrayal of Louis XV was so convincing that he became the first actor to win an Academy Award for Best Actor (though for later films)

- The film was so successful in America that it led to Ernst Lubitsch being recruited by Hollywood, where he would become one of the most respected directors of his generation

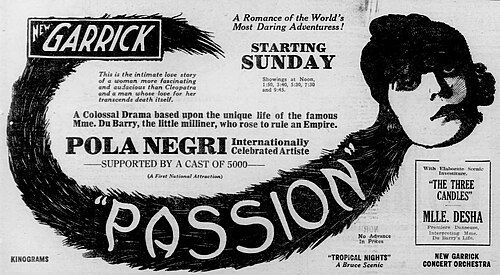

- A different version was released in the United States titled 'Passion' with some scenes altered to appeal to American audiences

- The film's lavish production values set a new standard for historical epics and influenced many subsequent films in the genre

- The guillotine scene was considered so shocking that some countries required it to be cut from the theatrical release

- Pola Negri and Ernst Lubitsch were romantically involved during production, which added tension to the set given her character's romantic entanglements

- The film was one of the first major productions of the newly formed UFA studio, established in 1917

- Despite being a silent film, the production employed a full orchestra during filming to help actors with timing and emotional expression

- The original negative was thought lost for decades but was discovered and restored in the 1990s

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film for its lavish production values and powerful performances. The New York Times hailed it as 'a masterpiece of cinematic art' while Variety noted its 'extraordinary visual splendor.' German critics particularly appreciated Lubitsch's sophisticated direction and the film's technical achievements. Modern critics view the film as a landmark achievement in silent cinema, with its influence still evident in contemporary historical dramas. Film historian David Thomson described it as 'the film that proved European cinema could compete with Hollywood on every level.' The performances of Negri and Jannings continue to be studied as examples of silent-era acting at its most nuanced and powerful.

What Audiences Thought

The film was enormously popular with audiences worldwide, breaking box office records in many countries. In Germany, it became a cultural phenomenon, with audiences returning multiple times to see its splendor. American audiences were particularly captivated by Pola Negri's performance, making her an instant star in the United States. The film's romantic elements and historical spectacle appealed to a broad demographic, from working-class audiences to the cultural elite. In some countries, the film's political undertones resonated with audiences experiencing their own revolutionary changes. The film's success led to increased demand for European films in international markets and helped establish the global film distribution system.

Awards & Recognition

- Best Foreign Film - Photoplay Magazine (1920)

- Best Artistic Production - German Film Critics Association (1919)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The historical novels of Alexandre Dumas

- Italian historical epics of the 1910s

- German Romantic literature

- French Revolutionary history

- Stage melodramas of the 19th century

This Film Influenced

- The Merry Widow (1925)

- The Love Parade (1929)

- Marie Antoinette (1938)

- Gone with the Wind (1939)

- The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was partially lost for several decades, with only incomplete versions surviving. However, a nearly complete print was discovered in the 1990s in a Russian archive and has since been restored by the Munich Film Museum. The restoration included reconstructing missing scenes from production stills and script fragments. The restored version premiered at the 1998 Berlin International Film Festival to critical acclaim. The film is now preserved in several archives worldwide, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the British Film Institute.