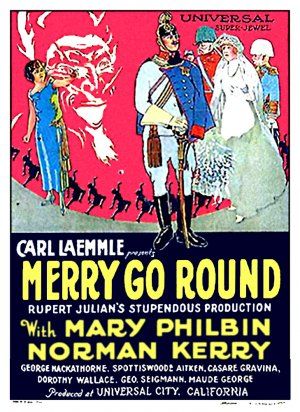

Merry-Go-Round

"A Tale of Two Loves - One of Duty, One of Desire"

Plot

Count Franz von Hohenegg, a charming Austrian nobleman, is forced into an arranged marriage with the daughter of his country's war minister to save his family's estate from financial ruin. While traveling to Vienna for the wedding, he poses as a necktie salesman and encounters a beautiful young woman named Agnes, who works as a circus puppeteer's daughter. Despite his engagement, Franz falls deeply in love with Agnes and must navigate the treacherous waters of duty versus passion, ultimately facing the consequences of his deception and the impossible choice between his aristocratic obligations and his heart's true desire.

About the Production

The film was originally intended to be directed by Erich von Stroheim, who had begun production and completed some scenes. However, Universal Pictures executive Carl Laemmle fired von Stroheim due to his extravagant spending and slow pace, replacing him with Rupert Julian. This was a notorious incident in Hollywood history as von Stroheim was known for his perfectionism and attention to detail. The production was completed with significant changes to von Stroheim's original vision.

Historical Background

The film was produced during a pivotal period in Hollywood history when the studio system was solidifying its control over production. 1923 was also a year of significant social change in America, with the 'Roaring Twenties' in full swing and traditional values being questioned. The film's themes of class conflict and arranged marriage reflected the changing attitudes toward social hierarchies and individual freedom. Post-WWI Europe was still recovering, and American audiences were fascinated by European aristocracy, which this film exploited. The year also saw the rise of the 'star system' in Hollywood, with actors like Mary Philbin and Norman Kerry becoming major draws. The film industry was transitioning from short films to feature-length productions, and studios like Universal were investing heavily in elaborate productions to compete with established studios like Paramount and MGM.

Why This Film Matters

'Merry-Go-Round' represents an important transitional moment in Hollywood history, marking the beginning of studio executives' willingness to intervene in creative decisions. The von Stroheim firing became a cautionary tale about the limits of directorial autonomy in the studio system. The film also exemplifies the silent era's fascination with European aristocracy and the 'exotic' other, reflecting America's growing cultural confidence in the post-WWI period. Its exploration of class boundaries and romantic freedom anticipated the more liberated social attitudes of the later 1920s. The film's circus setting also contributed to the popularization of circus imagery in American cinema, which would become a recurring motif in films ranging from 'He Who Gets Slapped' (1924) to 'The Greatest Showman' (2017).

Making Of

The production of 'Merry-Go-Round' was marked by one of early Hollywood's most notorious director firings. Erich von Stroheim, known as 'The Man You Love to Hate' for his demanding perfectionism and extravagant budgets, was originally hired to direct. He had already spent an estimated $100,000 on elaborate sets and costumes when Universal Pictures head Carl Laemmle visited the set. Horrified by von Stroheim's slow pace and mounting costs, Laemmle famously told him, 'You're fired!' and replaced him with Rupert Julian, who had just completed the successful 'The Hunchback of Notre Dame.' The cast was reportedly devastated by the change, as they had been working closely with von Stroheim for weeks. Julian had to complete the film using von Stroheim's existing footage and sets, though he made significant changes to the story's tone and pacing. The incident became legendary in Hollywood as an early example of studio executives exercising creative control over directors.

Visual Style

The film featured the distinctive cinematography style of the early 1920s, with dramatic lighting and carefully composed shots. The circus sequences utilized innovative camera movements for the time, including tracking shots that followed the performers. The visual contrast between the aristocratic world of Vienna and the colorful, chaotic world of the circus was emphasized through different lighting techniques and color tinting. Some scenes reportedly used von Stroheim's preferred naturalistic lighting style, while others reflected Julian's more theatrical approach. The film made effective use of shadows and silhouettes, particularly in the romantic scenes between the leads.

Innovations

The film featured elaborate set designs that were considered state-of-the-art for 1923, including a detailed recreation of a European circus and grand Viennese interiors. The production utilized innovative lighting techniques to create mood and atmosphere, particularly in the night scenes. The film also employed early forms of special effects, including matte paintings and double exposure techniques. The circus sequences required complex choreography and coordination between performers and camera operators, demonstrating the growing sophistication of film production techniques in the early 1920s.

Music

As a silent film, 'Merry-Go-Round' would have been accompanied by live musical accompaniment in theaters. The original score was composed by William Axt and compiled from various classical and popular pieces of the era. The music emphasized the film's romantic and dramatic elements, with waltzes for the Viennese scenes and more lively circus music for the carnival sequences. Modern screenings typically use newly composed scores or period-appropriate compiled scores to recreate the original viewing experience.

Famous Quotes

"In this world, we must all play our parts, even if our hearts speak a different truth." - Count Franz von Hohenegg

"Love knows no station, no class, no boundary - only the truth of two hearts beating as one." - Agnes

"A crown is but a burden when it weighs heavier than love itself." - Count Franz von Hohenegg

Memorable Scenes

- The dramatic first meeting between Franz and Agnes at the circus, where he watches her perform with her puppets and is immediately captivated by her beauty and innocence; The tense confrontation scene where Franz must choose between his duty to his family and his love for Agnes; The climactic circus sequence where Franz reveals his true identity to Agnes amidst the chaos and color of the carnival performance

Did You Know?

- This was the first major film where Erich von Stroheim was fired as director during production, setting a precedent for studio intervention in creative control

- Mary Philbin was chosen for the lead role after her success in 'The Phantom of the Opera' (1925), though this film was actually released earlier

- The film's title 'Merry-Go-Round' refers to the circus setting where much of the romance takes place, symbolizing the circular nature of love and fate

- Norman Kerry and Mary Philbin would later star together again in 'The Phantom of the Opera' (1925)

- Some of von Stroheim's original footage was reportedly used in the final cut, though it's impossible to determine exactly which scenes

- The film was considered quite scandalous for its time due to its themes of adultery and class conflict

- Universal Pictures heavily promoted the film as having been 'directed by the man who brought you The Hunchback of Notre Dame' referring to Rupert Julian's work

- The original European setting was created entirely on Universal's backlot, as location shooting was rare and expensive in 1923

- The film featured elaborate circus sequences that required weeks of preparation and training of performers

- Despite the production troubles, the film was one of Universal's more prestigious productions of 1923

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics were generally positive about the film, praising Mary Philbin's performance and the film's visual spectacle. The New York Times noted that 'despite its troubled production, the film emerges as a compelling romantic drama.' Modern critics, when able to view the film, have been more interested in its production history than its artistic merits, though some have praised its atmospheric cinematography and Philbin's emotive performance. The film is often discussed in film scholarship as an example of studio interference and the transition from director-driven to producer-driven cinema. Critics have noted that the film bears traces of von Stroheim's distinctive visual style despite Julian's direction.

What Audiences Thought

The film was moderately successful at the box office, benefiting from Universal's marketing campaign and the popularity of its stars. Audiences particularly responded to Mary Philbin's performance and the film's romantic elements. The circus sequences were especially popular with viewers, who appreciated the spectacle and visual entertainment value. However, the film did not achieve the blockbuster status of other Universal productions from the same period. Modern audiences rarely have the opportunity to see the film due to its limited availability, but when screened at silent film festivals, it has been well-received by classic cinema enthusiasts who appreciate its historical significance and melodramatic charm.

Awards & Recognition

- No known awards for this film

Film Connections

Influenced By

- European melodramas of the 1910s

- Viennese operetta traditions

- The works of Erich von Stroheim (particularly his visual style)

- Contemporary American society dramas

This Film Influenced

- The Merry Widow (1925)

- The Phantom of the Opera (1925) - through shared cast and similar romantic themes

- Circus films of the late 1920s

- Class-crossing romances of the early sound era

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is partially preserved with some scenes missing. A complete version has not been found, though surviving footage exists in several archives including the Library of Congress and the UCLA Film and Television Archive. The available prints are of varying quality, with some sequences showing significant deterioration due to the nitrate film stock used in the 1920s. Restoration efforts have been limited due to the incomplete nature of the surviving materials.