Nero, or The Fall of Rome

Plot

Roman emperor Nero has grown tired of his wife Octavia and becomes infatuated with the beautiful Poppea. Using his imperial power, Nero succeeds in making Poppea the new empress, replacing Octavia against the will of the Roman people. This decision sparks outrage among the populace, who view the emperor's actions as tyrannical and immoral. As opposition to his rule grows stronger and rumors of an imminent popular uprising reach Nero, he makes the fateful decision to set fire to Rome. From his terrace, Nero watches the city burn, rejoicing in the destruction while playing his lyra, ultimately sealing his own downfall as the empire turns against him in the epic conclusion of this historical tragedy.

About the Production

This was one of the early historical epics produced by the Italian film industry, which would later become famous for large-scale historical spectacles. The film utilized elaborate sets and costumes to recreate ancient Rome, showcasing the growing technical capabilities of Italian cinema in the early 1900s. Director Luigi Maggi was not only behind the camera but also appeared in front of it, demonstrating the multi-talented nature of early filmmakers who often wore multiple hats during production. The burning of Rome sequence required innovative special effects techniques that were advanced for 1909, using multiple exposures and careful staging to create realistic fire effects.

Historical Background

The year 1909 was a pivotal moment in cinema history, as the medium was transitioning from simple novelty attractions to sophisticated storytelling. Italian cinema was particularly flourishing during this period, with studios like Itala Film leading the way in producing ambitious historical epics. The film emerged during a time when Italy was experiencing rapid industrialization and social change, with ancient Roman history serving as a way to explore contemporary themes of power, corruption, and social upheaval. The choice of Nero as a subject was particularly relevant, as his story of tyranny and downfall resonated with modern audiences concerned about authoritarian rule. The film also reflected the growing national pride in Italy's Roman heritage, which was being rediscovered and celebrated through the new medium of cinema. This period saw the emergence of film as a serious art form capable of tackling complex historical and moral themes, with Italian studios at the forefront of this artistic revolution.

Why This Film Matters

'Nero, or The Fall of Rome' holds an important place in film history as an early example of the historical epic genre that would later flourish in Italian cinema. The film helped establish Italy's reputation for producing lavish historical spectacles, a tradition that would culminate in masterpieces like 'Cabiria' (1914) and later Hollywood epics like 'Ben-Hur' (1959). The portrayal of Nero as a tyrannical, decadent ruler became an archetype that would influence countless subsequent films about Roman emperors. The film's visual style and approach to historical storytelling influenced a generation of filmmakers working in the epic genre. It also demonstrated cinema's potential to bring history to life for mass audiences, making the past accessible and relevant to contemporary viewers. The burning of Rome sequence, in particular, set a standard for spectacular disaster scenes that would become a staple of historical epics. The film's success helped pave the way for Italy's dominance in the historical epic genre during the silent era.

Making Of

The making of 'Nero, or The Fall of Rome' represented a significant undertaking for Italian cinema in 1909. The production required elaborate sets to recreate ancient Rome, including detailed recreations of Roman architecture, palaces, and streets. The fire scenes were particularly challenging to film, requiring careful coordination to create realistic effects while ensuring the safety of cast and crew. Director Luigi Maggi, who also acted in the film, was part of a generation of filmmakers who were essentially inventing the language of cinema as they worked. The cast, led by Alberto Capozzi as Nero, had to rely heavily on physical acting and expressive gestures to convey emotion, as silent films depended entirely on visual storytelling. The film's production by Itala Film represented the studio's commitment to ambitious historical subjects that would showcase Italian cinema's growing technical and artistic capabilities. The burning of Rome sequence required multiple takes and careful planning, with the crew using various techniques including miniatures, controlled fires, and clever editing to create the illusion of a city in flames.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'Nero, or The Fall of Rome' utilized the techniques available in 1909 to create visually striking images of ancient Rome. The film employed static camera positions typical of the era, but used careful composition and staging to create dramatic visual effects. The lighting would have been natural or basic studio lighting, but was used effectively to create mood and highlight important moments in the narrative. The burning of Rome sequence required innovative techniques to create realistic fire effects, possibly using multiple exposures or in-camera effects combined with practical fire elements. The film's visual style emphasized grand tableaus and carefully composed scenes that showcased the elaborate sets and costumes. While limited by the technology of the time, the cinematography successfully created the epic scope necessary for the historical subject matter and helped establish visual conventions that would influence later historical epics.

Innovations

For its time, 'Nero, or The Fall of Rome' represented several technical achievements in early cinema. The film's production of the burning of Rome sequence required innovative special effects techniques that were advanced for 1909, including the use of miniatures, controlled fires, and multiple exposure photography. The elaborate sets and costumes demonstrated the growing sophistication of film production design in Italian cinema. The film's use of multiple scenes and locations showed an advancement in narrative complexity compared to earlier simple films. The production likely utilized some of the earliest camera movement techniques, though these would have been limited by the heavy equipment of the era. The film's editing, while basic by modern standards, showed an understanding of how to build dramatic tension through the juxtaposition of different shots. These technical achievements, while modest compared to later films, were significant steps forward in the development of cinema as an art form capable of complex historical storytelling.

Music

As a silent film, 'Nero, or The Fall of Rome' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The specific musical score is not documented, but it likely consisted of classical pieces or specially composed music that enhanced the dramatic action on screen. The accompaniment might have included a piano, organ, or small orchestra depending on the theater's resources and the importance of the screening. The music would have been particularly important during the burning of Rome sequence, where dramatic musical cues would have heightened the tension and spectacle of the scene. The tradition of live musical accompaniment for silent films meant that each screening could have a slightly different musical interpretation, with the accompanist responding to the on-screen action and audience reactions. The absence of recorded sound made the visual storytelling and musical accompaniment crucial elements in creating the film's emotional impact.

Famous Quotes

Memorable Scenes

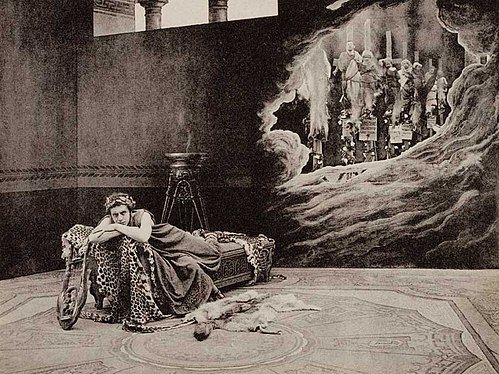

- The climactic sequence where Nero watches Rome burn from his terrace while playing his lyra, rejoicing in the destruction he has ordered. This scene became an iconic image of imperial decadence and would be referenced in countless later films about the Roman emperor.

- The dramatic confrontation scene where Nero dismisses his wife Octavia in favor of Poppea, showcasing the emperor's tyrannical abuse of power and setting the stage for the popular uprising.

- The tense moment when Nero is informed of the imminent popular uprising, leading to his fateful decision to burn the city rather than face the consequences of his actions.

Did You Know?

- This film was produced during the golden age of Italian silent cinema, when the country was emerging as a major force in international filmmaking.

- Director Luigi Maggi was one of Italy's pioneering filmmakers, having started his career as an actor before moving behind the camera.

- The film's depiction of Nero playing his lyre while Rome burns became an iconic image that would be referenced in countless later films about the Roman emperor.

- Itala Film, the production company, was one of Italy's most important early film studios and would go on to produce many historical epics.

- The film was part of a wave of historical spectacles that established Italy's reputation for lavish productions in the silent era.

- Alberto Capozzi, who played Nero, was one of Italy's first film stars and appeared in over 100 films during his career.

- The film's focus on the decadence and corruption of power reflected contemporary concerns about modern society, using ancient Rome as a metaphor.

- Like many films of this era, it was accompanied by live musical performance during theatrical screenings.

- The film's running time was typical of early 1900s productions, which were generally shorter than later feature films.

- The production used some of the most sophisticated special effects available at the time to depict the burning of Rome.

- The film was released internationally, helping establish Italian cinema's reputation for historical epics.

- Lydia De Roberti, who played Poppea, was one of the early Italian film actresses known for her dramatic performances.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of 'Nero, or The Fall of Rome' was generally positive, with reviewers praising the film's ambitious scope and impressive production values. Critics of the time noted the film's effective use of sets and costumes to create an authentic Roman atmosphere. The performance of Alberto Capozzi as Nero was particularly highlighted for its intensity and dramatic power. Modern film historians view the film as an important early example of the historical epic genre, noting its influence on later Italian and Hollywood productions. While some aspects of the film may seem dated to contemporary viewers, critics acknowledge its historical importance and the technical achievements it represented for its time. The film is often cited in studies of early cinema as an example of how quickly filmmakers were developing the language of visual storytelling and the potential of cinema as a medium for historical drama.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1909 were reportedly captivated by 'Nero, or The Fall of Rome,' which offered them a spectacular vision of ancient Roman history brought to life through the new medium of cinema. The film's dramatic story of imperial decadence and downfall resonated with viewers, who were still experiencing the novelty of seeing historical events recreated on screen. The burning of Rome sequence was particularly popular with audiences, who were impressed by the scale of the spectacle and the technical wizardry involved in creating the fire effects. The film's success helped demonstrate the commercial viability of historical epics, encouraging Italian studios to invest in increasingly ambitious productions. While modern audiences might find the film's pacing and acting style different from contemporary cinema, those interested in film history continue to appreciate its pioneering qualities and its place in the development of the historical epic genre.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Earlier Italian historical films

- Contemporary stage plays about Roman history

- Classical Roman historical sources (Tacitus, Suetonius)

- Earlier French historical epics

- Contemporary opera treatments of Roman themes

- 19th century Romantic paintings of Roman subjects

This Film Influenced

- Quo Vadis? (1913)

- Cabiria (1914)

- The Sign of the Cross (1932)

- Quo Vadis (1951)

- Ben-Hur (1959)

- The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964)

- Nero (1977 TV miniseries)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The preservation status of 'Nero, or The Fall of Rome' (1909) is uncertain, as is common with films from this very early period of cinema. Many films from the 1900s have been lost due to the fragile nature of early film stock and inadequate preservation methods. However, some Italian films from this era have survived in archives or private collections. The film may exist in whole or in part in film archives such as the Cineteca Nazionale in Italy or other international film preservation institutions. Restoration efforts for early Italian films have been ongoing, so it's possible that portions or all of the film may have been preserved or restored. Film historians continue to search for lost films from this period in archives and private collections worldwide, hoping to recover important works from cinema's pioneering years.