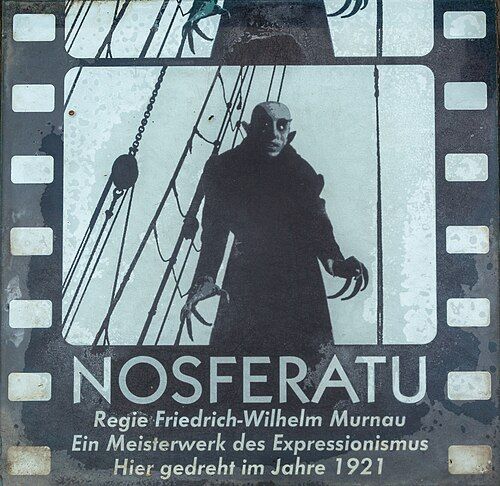

Nosferatu

"Die frevelhafte Begegnung mit dem Ungeheuer! (The sinful encounter with the monster!)"

Plot

Thomas Hutter, a young real estate agent from Wisborg, Germany, is sent by his employer Knock to Transylvania to finalize a property sale with the mysterious Count Orlok. After a harrowing journey through superstitious countryside, Hutter arrives at Orlok's decrepit castle where he discovers the Count is a vampire who feeds on blood. Orlok becomes obsessed with Hutter's wife Ellen after seeing her photograph, and follows Hutter back to Wisborg by ship, bringing death and plague with him. As the town is ravaged by mysterious deaths, Ellen learns from a book of vampires that she can defeat Orlok by offering her pure blood to him until dawn, when sunlight will destroy him. In a final sacrificial act, Ellen succeeds in her plan, ending Orlok's reign of terror but dying herself in the process, while the crazed Knock is captured and the town begins to recover from the vampire's curse.

About the Production

The film was shot in 1921 during a period of hyperinflation in Germany, which made production challenging. Director F.W. Murnau insisted on shooting on location to achieve authentic atmosphere, unusual for the time. The production faced significant secrecy to avoid copyright infringement claims from Bram Stoker's estate. Max Schreck remained in character as Count Orlok throughout filming, even eating meals in his vampire makeup, which terrified the cast and crew. The famous scenes of Orlok's shadow climbing stairs were achieved through innovative use of negative photography and carefully controlled lighting.

Historical Background

Nosferatu was produced in Germany during the Weimar Republic, a period of intense cultural flowering amid political instability and economic hardship. The country was experiencing hyperinflation in 1921-1922, which made film production both challenging and attractive as an investment. The German Expressionist movement was at its peak, with films like The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) having already established the visual style that would influence Nosferatu. The trauma of World War I and the Spanish Flu pandemic (1918-1920) were still fresh in the collective consciousness, contributing to the film's themes of plague and death. The rise of psychoanalysis and interest in the occult in post-war Germany also influenced the film's exploration of repressed desires and supernatural forces. Additionally, the film reflected contemporary anxieties about foreign influences (Orlok as the Eastern 'other') and disease, themes that resonated strongly with German audiences of the time.

Why This Film Matters

Nosferatu is arguably the most influential horror film ever made, establishing numerous vampire tropes that persist in cinema today. It was the first film adaptation of Dracula and, despite being unauthorized, set the visual template for how vampires would be portrayed for decades. The film's use of shadow and light created a visual language of horror that directors continue to emulate. Nosferatu introduced the concept that sunlight destroys vampires, a convention not present in Stoker's novel but now standard in vampire mythology. The film's expressionist style influenced not just horror but film noir and other genres. Count Orlok's rodent-like appearance and association with plague created a connection between vampirism and disease that has resonated through subsequent vampire films. The movie's survival despite attempts to destroy it has made it a symbol of artistic persistence and the difficulty of suppressing cultural works. Its influence can be seen in countless films, from Universal's horror classics of the 1930s to modern interpretations like Werner Herzog's 1979 remake and contemporary vampire films.

Making Of

The production of Nosferatu was shrouded in secrecy from the beginning. Director F.W. Murnau and producer Albin Grau deliberately avoided acquiring the rights to Bram Stoker's Dracula, planning to make an unauthorized version while changing character names and details. Grau, an occult enthusiast and artist, had been inspired by stories of vampires from his experiences in Serbia during World War I. Max Schreck, a stage actor with little film experience, was cast as Count Orlok and committed completely to the role, wearing prosthetic teeth, ears, and makeup designed by Grau. The cast and crew were reportedly terrified of Schreck in character, as he maintained his vampire persona between takes. The production filmed on location in the Baltic Sea region during autumn and winter to capture the desolate atmosphere Murnau desired. The famous shadow effects were created by placing actors far from screens and using powerful lights, with Orlok's elongated fingers achieved through special gloves. When the film was released, Florence Stoker, Bram Stoker's widow, immediately sued for copyright infringement and won, leading to a court order that all copies be destroyed. However, the film had already been distributed internationally, and several prints survived, ensuring its preservation as a cinematic masterpiece.

Visual Style

The cinematography of Nosferatu, credited to Fritz Arno Wagner and Günther Krampf, revolutionized horror filmmaking through its innovative use of light and shadow. The film employed the German Expressionist style of distorted sets and dramatic lighting to create an atmosphere of dread and unease. Wagner pioneered the use of negative photography to create supernatural effects, particularly in scenes showing Orlok's powers. The cinematography made extensive use of chiaroscuro lighting, with deep shadows that suggested unseen horrors. The famous scene of Orlok's shadow ascending the stairs was achieved through carefully controlled lighting and camera positioning, creating an image more terrifying than showing the vampire himself. The film also utilized innovative techniques such as fast motion to create the effect of Orlok's supernatural speed, and multiple exposures for ghostly appearances. The location shooting in natural settings, combined with studio work, created a unique visual texture that blended realism with expressionism. The cinematography's emphasis on shadows became a defining characteristic of film noir and horror cinema for decades to come.

Innovations

Nosferatu pioneered numerous technical innovations that would become standard in filmmaking. The film's use of location shooting, combined with studio work, was unusual for its time and created a unique visual authenticity. The cinematography employed innovative techniques including negative photography for supernatural effects, fast motion to suggest vampire speed, and multiple exposures for ghostly appearances. The film's special effects team created convincing scenes of Orlok's carriage traveling without horses and his ability to pass through locked doors. The makeup design for Count Orlok, created by Albin Grau, was revolutionary in its grotesque realism and influenced horror makeup for decades. The film also pioneered the use of color tinting to enhance mood, with blue tones for night scenes and sepia for daylight. The editing techniques, particularly the cross-cutting between Ellen's sacrifice and Orlok's demise, created suspense and emotional impact that influenced film editing practices. The production's use of miniature models for certain shots, such as the ship sailing through stormy seas, demonstrated early mastery of practical effects.

Music

As a silent film, Nosferatu was originally accompanied by live musical performances that varied by theater. The original score composed by Hans Erdmann has been mostly lost, with only fragments surviving in archives. Erdmann's music was designed to enhance the film's atmosphere through leitmotifs for different characters and situations. Modern restorations have used various approaches to recreate or replace the score, including classical music selections, newly composed scores, and experimental electronic music. Some screenings feature live organ or piano accompaniment in the traditional silent film style. The 1995 restoration by the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung included a new score by Berndt Heller based on Erdmann's original fragments. The lack of a definitive original soundtrack has allowed for diverse musical interpretations of the film over the decades, each bringing different emotional textures to Murnau's visuals.

Famous Quotes

Is this your wife? What a lovely throat.

When the cross was raised, he fell back.

The blood is the life!

Your wife has a beautiful neck.

I will see you again soon.

Wisborg will be cleansed by morning.

The vampire sleeps during the day, but at night he rises.

The book says that a virtuous woman can defeat the Nosferatu through sacrifice.

Memorable Scenes

- Count Orlok's shadow climbing the staircase - one of cinema's most iconic images, created through innovative use of shadow and light to suggest the vampire's supernatural presence without showing him directly

- The first reveal of Count Orlok as he rises from his coffin - a shocking moment that established the grotesque, rat-like appearance that would define vampire imagery

- The scene of rats pouring out of the ship's hold in Wisborg harbor - symbolizing the spread of plague and evil that Orlok brings with him

- Ellen's sacrifice as she offers herself to Orlok to save the town - a powerful sequence combining horror with themes of redemption and selflessness

- Orlok's journey across the sea on the ship - filled with ominous foreshadowing and death, establishing the vampire as a force of nature

- The final scene of Orlok vanishing in the sunlight - pioneering the concept that vampires are destroyed by daylight

Did You Know?

- The film was an unauthorized adaptation of Bram Stoker's 1897 novel 'Dracula', with character names changed to avoid copyright infringement (Count Dracula became Count Orlok, Van Helsing became Professor Bulwer, etc.)

- Max Schreck's performance was so convincing that rumors circulated for decades that he was actually a real vampire hired for the role

- Prana Film, the production company, declared bankruptcy immediately after the film's release to avoid paying legal fees when Bram Stoker's widow successfully sued for copyright infringement

- The original title was to be 'Nosferatu - Eine Symphonie des Grauens' (Nosferatu - A Symphony of Horror)

- Many original prints were destroyed following the lawsuit, making surviving copies extremely valuable historically

- The film pioneered the use of negative photography for special effects, particularly in scenes showing Orlok's supernatural powers

- Count Orlok's distinctive appearance was based on historical accounts of Vlad the Impaler and Jewish stereotypes of the time, though this was not Murnau's intention

- The ship scene where rats pour out of the coffin used real rats that had been painted and trained for the sequence

- F.W. Murnau filmed multiple takes of every scene at different times of day to capture various lighting conditions

- The film's influence on vampire mythology includes establishing that vampires are killed by sunlight (not present in Stoker's original novel)

What Critics Said

Upon its initial release, Nosferatu received mixed reviews from critics, with some praising its atmospheric qualities while others found it too grotesque. Many German critics of the time dismissed it as exploitation cinema. However, critics in other countries, particularly France, recognized its artistic merits early on. As decades passed, critical opinion shifted dramatically, with Nosferatu now universally regarded as a masterpiece of cinema. Critics praise F.W. Murnau's direction, Max Schreck's performance, and the film's innovative use of shadow and atmosphere. Modern critics consistently rank it among the greatest films ever made, with particular emphasis on its influence on horror cinema and its technical achievements. The film is now studied in film schools worldwide as a prime example of German Expressionism and early horror cinema.

What Audiences Thought

Initial audience reactions to Nosferatu were divided, with many finding the film genuinely terrifying. Reports from early screenings described audience members fainting or fleeing the theater during particularly frightening scenes. The film's unsettling atmosphere and Schreck's grotesque performance proved too intense for some viewers of the era. However, it developed a cult following among horror enthusiasts even as legal issues limited its distribution. Over the decades, audience appreciation has grown exponentially, with the film now regarded as a classic of horror cinema. Modern audiences often express surprise at how effectively the silent film creates tension and dread without dialogue or sound effects. The film has become a Halloween tradition for many cinephiles and continues to draw audiences to revival screenings and special events featuring live musical accompaniment.

Awards & Recognition

- No major awards were given to the film upon its release due to the legal controversies and limited distribution

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Bram Stoker's 'Dracula' (1897) - the primary literary source

- The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) - German Expressionist style

- Gothic literature tradition

- German folklore and vampire legends

- Folk tales from the Balkans region

- Expressionist art movement

- The works of Edgar Allan Poe

- Medieval vampire myths and superstitions

This Film Influenced

- Dracula (1931)

- Vampyr (1932)

- Horror of Dracula (1958)

- The Night of the Hunter (1955)

- Shadow of the Vampire (2000)

- Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979)

- Bram Stoker's Dracula (1992)

- Let the Right One In (2008)

- Only Lovers Left Alive (2013)

- The Witch (2015)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Nosferatu has a complex preservation history due to the copyright lawsuit that ordered most copies destroyed. Several prints survived in different countries, resulting in various versions with different running times and scene arrangements. The most complete version is a 1995 restoration by the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung, which compiled footage from multiple sources including a 16mm print found in the 1980s. The film has been preserved by the Library of Congress and selected for the National Film Registry in 2022. Multiple restorations have been undertaken over the decades, with the most recent being a 4K restoration completed in 2022 for the film's centenary. Despite the loss of the original camera negative and much of Hans Erdmann's musical score, Nosferatu survives in remarkably good condition compared to other films of its era, allowing modern audiences to experience Murnau's vision nearly as intended.