Oliver Twist

"The Classic Story of a Boy Who Dared to Ask for More!"

Plot

Nine-year-old orphan Oliver Twist endures a miserable existence in a Victorian workhouse where he and his fellow orphans are starved on meager rations of gruel. When Oliver courageously asks Mr. Bumble for more food, he is punished and sold as an apprentice to an undertaker, where he faces further cruelty and abuse. Oliver escapes to London and falls in with the Artful Dodger, a streetwise pickpocket who introduces him to Fagin, the cunning leader of a gang of young thieves. Oliver is reluctantly trained in the art of pickpocketing but maintains his innocence despite the criminal environment. After being wrongly accused of theft, Oliver is taken in by the kind and wealthy Mr. Brownlow, who offers him a chance at a better life. However, Fagin and his violent associate Bill Sikes, fearing Oliver might expose their criminal operations, plot to kidnap the boy and drag him back into their world of crime.

About the Production

This was one of Monogram Pictures' early prestige productions, attempting to elevate their typical B-movie output with a literary adaptation. The film was shot on a modest budget typical of Poverty Row studios, with minimal sets and limited location shooting. The production faced challenges in creating Victorian London atmosphere within their financial constraints, relying heavily on studio backlots and creative set design. Director William J. Cowen, primarily known as a screenwriter, was given this assignment as one of his few directorial efforts.

Historical Background

The 1933 release of 'Oliver Twist' occurred during one of the darkest periods of the Great Depression, making Dickens' critique of social inequality and poverty particularly relevant to American audiences. The film industry was transitioning from the early sound era to more sophisticated filmmaking techniques, with studios like Monogram trying to establish themselves alongside major studios. The Production Code had just begun being enforced in 1934, so this film represents one of the last pre-code literary adaptations. The early 1930s saw increased interest in social issues in cinema, with films addressing poverty and injustice finding receptive audiences. This adaptation also reflects the period's fascination with British literature, as American studios frequently adapted classic English novels for the screen. The film's release coincided with Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal policies, which were addressing many of the same social issues Dickens wrote about in Victorian England.

Why This Film Matters

While overshadowed by later adaptations, the 1933 'Oliver Twist' holds significance as an early sound version of Dickens' work and represents the ambitions of Poverty Row studios to tackle literary classics. It demonstrates how classic literature was adapted for early sound cinema, with the limitations and opportunities that technology presented. The film reflects American interpretations of British social issues, filtered through the lens of Depression-era concerns about poverty and social welfare. Its existence shows the enduring appeal of Dickens' stories across different eras and mediums. The preservation of this film provides valuable insight into 1930s filmmaking practices outside the major studio system. It also represents an important step in the long tradition of Oliver Twist adaptations that would continue through the decades, each reflecting their own time's concerns and cinematic capabilities.

Making Of

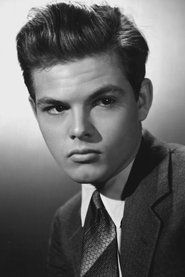

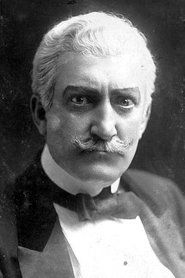

The production of this 1933 adaptation was typical of Poverty Row filmmaking, with tight schedules and limited resources. Director William J. Cowen, primarily a screenwriter making one of his rare directorial forays, had to work quickly to complete the film within Monogram's budget constraints. The young Dickie Moore was already an experienced child actor, having appeared in numerous films, but the emotional demands of playing Oliver proved challenging. The studio reused sets from other productions to create the Victorian London atmosphere, and costumes were often rented or repurposed. Irving Pichel's portrayal of Fagin was controversial even then, as it followed the traditional theatrical interpretation that some critics found antisemitic, though this was common in adaptations of the period. The film was shot in just a few weeks, with the child actors' working hours strictly limited by newly enforced labor laws. Despite the budget limitations, the production team attempted to create authentic period detail through careful set dressing and costume design.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Ira H. Morgan reflects the technical limitations and stylistic conventions of early 1930s Poverty Row productions. The film employs static camera work typical of early sound films, with limited camera movement due to bulky sound recording equipment. Lighting is high-key with limited shadow play, characteristic of the era's approach to family entertainment. The Victorian London atmosphere is created through careful set design rather than location shooting, with the cinematography focusing on creating depth within confined studio spaces. Morgan makes effective use of close-ups, particularly in scenes featuring the child actors, to emphasize emotional moments. The visual style prioritizes clarity and narrative function over artistic experimentation, reflecting both budget constraints and the practical needs of storytelling in early sound cinema.

Innovations

While not groundbreaking in technical terms, the film represents the typical technical standards of early 1930s Poverty Row productions. The sound recording uses Western Electric equipment, standard for the era but with noticeable limitations in clarity and range. The film was shot on 35mm black and white film stock, with the cinematography adapted to the sensitivity limitations of the film available in 1933. The production made creative use of limited studio space through careful set design and camera placement to create the illusion of Victorian London. The editing follows the continuity style that was becoming standard in the early sound era, with longer takes due to the technical challenges of cutting sound footage. The film demonstrates how smaller studios adapted major studio techniques within their budget constraints, achieving professional results despite limited resources.

Music

The musical score was composed by Lee Zahler, Monogram Pictures' house composer who created music for numerous low-budget productions during this period. The soundtrack features typical early 1930s orchestral arrangements with limited instrumentation due to budget constraints. The music serves primarily as accompaniment rather than a narrative device, with leitmotifs used sparingly to identify key characters and emotional moments. As was common in early sound films, the score was recorded live during filming sessions, limiting the complexity of the musical arrangements. The film includes no original songs, relying instead on classical and period-appropriate musical themes to establish the Victorian setting. The sound quality reflects the technical limitations of early sound recording equipment, with some noticeable background noise and limited dynamic range.

Famous Quotes

"Please, sir, I want some more." - Oliver Twist to Mr. Bumble

"In this life, one thing counts: In the bank, large amounts." - Fagin

"I'm not afraid, sir. I'm not afraid of anything." - Oliver Twist

"The law is a ass, a idiot." - Mr. Brownlow

"There's a bright side to everything." - The Artful Dodger

Memorable Scenes

- The iconic workhouse scene where Oliver timidly approaches Mr. Bumble and asks for more gruel, sparking outrage among the authorities and setting his journey in motion.

- Oliver's first encounter with the Artful Dodger in the streets of London, where the streetwise boy offers him food and shelter, introducing him to Fagin's world.

- The training scene where Fagin teaches Oliver and other boys the art of pickpocketing using handkerchiefs and wallets, showcasing the criminal education of innocent children.

- Oliver's rescue by Mr. Brownlow after being falsely accused of theft, representing the kindness and justice he has long sought.

- The tense confrontation between Bill Sikes and Fagin over Oliver's fate, highlighting the violent nature of the criminal underworld.

Did You Know?

- This was the first sound film adaptation of Charles Dickens' Oliver Twist, predating the more famous 1948 David Lean version by 15 years.

- Dickie Moore, who played Oliver, was one of the most popular child actors of the 1930s and would later appear in the Our Gang comedies.

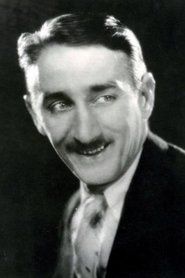

- William 'Stage' Boyd, who played Bill Sikes, added the 'Stage' nickname to his name to avoid confusion with another actor named William Boyd (who played Hopalong Cassidy).

- The film was produced by Monogram Pictures, a studio known for low-budget films, making this adaptation particularly notable for its ambitious literary source material.

- Irving Pichel, who played Fagin, would later become a successful director, helming films like 'Destination Moon' (1950).

- This adaptation was released during the Great Depression, which may have resonated with audiences given the story's themes of poverty and social injustice.

- The film was considered lost for many years before being discovered and preserved by film archives.

- Unlike many adaptations, this version includes the character of Monks, Oliver's half-brother, though his role is significantly reduced.

- The production code was just beginning to be enforced in 1933, which may have influenced how the criminal elements were portrayed.

- Child labor laws of the 1930s restricted how long Dickie Moore could work on set each day, affecting the shooting schedule.

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews were mixed but generally acknowledged the film's ambitions despite its obvious budget limitations. The New York Times noted that while the production lacked the polish of major studio films, it captured the spirit of Dickens' novel effectively. Variety praised Dickie Moore's performance as Oliver, calling it 'convincing and heartfelt,' while criticizing the film's technical shortcomings. Modern critics view the film as an interesting historical artifact, with its value lying more in its place in cinema history than its artistic merits. Film historians appreciate it as an example of how Poverty Row studios attempted to compete with major productions through literary adaptations. The performances, particularly those of the child actors, have been retrospectively praised for their authenticity within the constraints of 1930s acting styles.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1933 responded positively to the film, particularly families who were drawn to Dickens' familiar story and the appeal of child performers. The themes of poverty and social injustice resonated strongly with Depression-era viewers, many of whom saw parallels between Oliver's struggles and their own hardships. The film performed modestly at the box office for a Monogram production, helping establish the studio's reputation for producing accessible family entertainment. Modern audiences who have discovered the film through film society screenings and archive showings often appreciate its historical value and straightforward storytelling approach. The film has developed a cult following among classic film enthusiasts and Dickens adaptation collectors who value its place in cinematic history.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Charles Dickens' novel 'Oliver Twist' (1838)

- Previous stage adaptations of Dickens' work

- Silent film adaptations of literary classics

- British literary tradition

This Film Influenced

- Oliver Twist (1948)

- Oliver! (1968)

- Oliver Twist (2005)

- Various television adaptations

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was considered lost for decades but was discovered and preserved by film archives. A 35mm print exists in the Library of Congress collection, and the film has been made available through various classic film channels and archives. The preservation quality is decent for a Poverty Row production of its era, though some deterioration is evident. The film has been digitized for preservation purposes and is occasionally screened at film festivals specializing in classic cinema restoration.