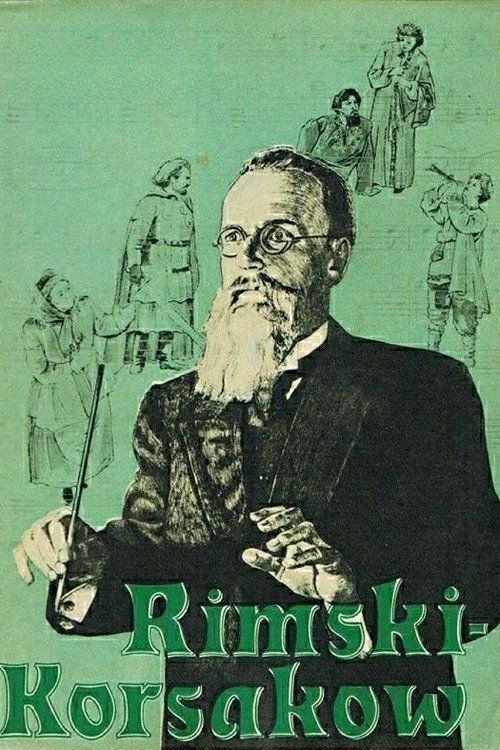

Rimsky-Korsakov

Plot

The biographical film 'Rimsky-Korsakov' chronicles the final twenty years of the renowned Russian composer's life, beginning in the late 1880s. The narrative focuses on Rimsky-Korsakov's tenure as a professor at the St. Petersburg Conservatory, where he mentored a new generation of Russian composers including Alexander Glazunov and Igor Stravinsky. The film depicts his political persecution following his support of student protests in 1905, which led to his dismissal from the Conservatory and being placed under police surveillance. Throughout these personal and professional struggles, the composer continues to create some of his most famous works, including 'The Golden Cockerel' and 'The Legend of the Invisible City of Kitezh.' The film culminates with Rimsky-Korsakov's death in 1908, leaving behind a rich musical legacy that would influence Russian classical music for generations to come.

About the Production

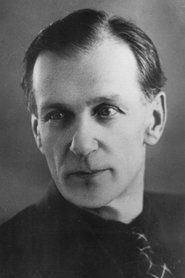

The film was produced during the final years of Stalin's rule, a period when Soviet biographical films were expected to emphasize the revolutionary and progressive aspects of historical figures. Director Grigoriy Roshal was known for his biographical films about cultural figures, having previously made films about Lenin and other Soviet heroes. The production faced the challenge of authentically recreating late 19th and early 20th century Russia, including detailed period costumes, sets, and musical performances.

Historical Background

The film was produced in 1952 during the final year of Joseph Stalin's rule and the height of the Cold War. This period saw a renewed emphasis in Soviet cultural policy on promoting Russian cultural heritage as a means of demonstrating Soviet cultural superiority to the West. The film was made under the influence of the Zhdanov Doctrine, which demanded that all art serve ideological purposes and present an optimistic, heroic vision of Soviet reality and Russian history. Biographical films of this era were expected to portray their subjects as progressive figures who contributed to the advancement of Russian culture toward socialism. The film's focus on Rimsky-Korsakov's political troubles and his support for student revolutionaries aligned with the Soviet narrative of historical figures who, despite living before the revolution, demonstrated proto-revolutionary consciousness. The production also benefited from the postwar expansion of Soviet film infrastructure, including improved color film technology and larger studio facilities at Mosfilm.

Why This Film Matters

'Rimsky-Korsakov' represents an important example of the Soviet biographical film genre that flourished in the postwar period. The film contributed to the Soviet project of claiming Russian cultural figures as part of the broader Soviet cultural heritage, even those who lived before the revolution. Its production demonstrated the Soviet Union's commitment to promoting classical music and high culture among the masses, making the life of a classical composer accessible to ordinary Soviet citizens. The film's international recognition, including its screening at Cannes, served as cultural diplomacy during the Cold War, showcasing Soviet artistic achievements to Western audiences. Within Soviet cinema, the film established conventions for musical biopics that would influence subsequent films about composers and musicians. The work also helped preserve and popularize Rimsky-Korsakov's music for new generations of Soviet listeners, many of whom might not have been familiar with classical repertoire.

Making Of

The making of 'Rimsky-Korsakov' was a significant undertaking for Mosfilm, requiring extensive historical research and musical preparation. Director Grigoriy Roshal worked closely with musicologists to ensure the accurate portrayal of the composer's creative process and the historical context of his works. The film's musical performances were recorded over several months with the USSR State Symphony Orchestra, requiring multiple takes to achieve the desired quality. Nikolai Cherkasov underwent extensive preparation for the role, studying Rimsky-Korsakov's mannerisms, conducting style, and even learning to play basic piano pieces to appear authentic in performance scenes. The costume department created over 200 period-accurate costumes, while the set design team meticulously recreated the interiors of 19th-century Russian aristocratic homes and the St. Petersburg Conservatory. The film's production coincided with the Zhdanov Doctrine era, which imposed strict ideological requirements on Soviet arts, requiring the filmmakers to emphasize the 'people's' and 'progressive' aspects of Rimsky-Korsakov's legacy while downplaying any elements that might be considered bourgeois.

Visual Style

The film's cinematography, handled by Vladimir Nikolaev, employed the relatively new Sovcolor process to create rich, period-appropriate visuals that captured the opulence of late 19th-century Russian aristocratic life. The camera work combines sweeping, epic shots of St. Petersburg landscapes with intimate close-ups during musical performance scenes, emphasizing both the grandeur of the historical setting and the personal nature of artistic creation. The film uses lighting techniques that contrast the warm, golden tones of creative moments with the harsher, more shadowed lighting of political confrontation scenes. The conservatory sequences feature carefully choreographed camera movements that follow the flow of musical performances, creating a visual rhythm that complements the musical content. The color palette emphasizes deep reds, golds, and rich browns to evoke the historical period while maintaining visual interest throughout the film's runtime.

Innovations

The film represented several technical achievements for Soviet cinema of the early 1950s. Its use of the Sovcolor process demonstrated the maturation of color film technology in the Soviet Union, with particularly successful results in capturing the rich textures of period costumes and the warm glow of candlelit scenes. The recording techniques for the musical performances were innovative for their time, using multiple microphones and recording equipment to capture the full dynamic range of orchestral performances. The film's editing successfully synchronized musical performances with visual elements, creating a seamless integration between sound and image that enhanced the viewing experience. The production also developed new techniques for recreating historical musical instruments and performance practices, contributing to the authenticity of the musical sequences. The film's special effects, particularly in scenes depicting operatic performances, used rear projection and matte painting techniques that were advanced for Soviet cinema of the period.

Music

The film's soundtrack features extensive selections from Rimsky-Korsakov's musical catalog, including excerpts from his most famous operas 'Sadko,' 'The Snow Maiden,' 'The Tale of Tsar Saltan,' and 'The Golden Cockerel.' The musical performances were recorded by the USSR State Symphony Orchestra under the direction of conductor Gennady Rozhdestvensky, ensuring authentic interpretations of the composer's works. The film's score weaves these pieces into the narrative, using them both as diegetic music within scenes and as underscoring to enhance emotional moments. The sound design emphasizes the acoustic properties of different performance spaces, from intimate salon settings to grand concert halls, creating a realistic auditory experience. The soundtrack album released in conjunction with the film became one of the most popular classical recordings in the Soviet Union, introducing many listeners to Rimsky-Korsakov's music for the first time.

Famous Quotes

Music is the art of thinking with sounds.

Without music, life would be a mistake.

The purpose of art is to lay bare the secrets of the human heart.

A composer's music should express his own life and experiences.

Teaching is the highest form of learning.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening scene showing Rimsky-Korsakov conducting one of his compositions with the St. Petersburg orchestra, establishing both his musical genius and his position in Russian cultural life

- The tense confrontation at the conservatory where Rimsky-Korsakov defends his students against political authorities, demonstrating his moral courage and commitment to artistic freedom

- The intimate scene where the composer works late into the night on 'The Golden Cockerel,' revealing his creative process and dedication to his art

- The emotional farewell scene at the conservatory after his dismissal, showing the impact of his teaching on his students

- The final scene depicting his funeral procession through St. Petersburg, symbolizing the passing of an era in Russian music

Did You Know?

- The film was part of a series of Soviet biographical films about cultural figures produced in the late 1940s and early 1950s, following the state's emphasis on promoting Russian cultural heritage

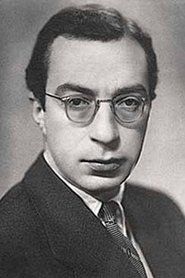

- Nikolai Cherkasov, who plays Rimsky-Korsakov, was one of the most celebrated actors in Soviet cinema, famous for his roles as Lenin and Ivan the Terrible

- The film features extensive musical performances of Rimsky-Korsakov's compositions, performed by the USSR State Symphony Orchestra

- Director Grigoriy Roshal was married to actress Vera Maretskaya, who appears in the film as Nadezhda Rimskaya-Korsakova, the composer's wife

- The film's release coincided with the 44th anniversary of Rimsky-Korsakov's death

- The production team consulted with musicologists and historians to ensure historical accuracy in depicting the composer's life and works

- The film was shot in color using the Sovcolor process, which was relatively new for Soviet cinema at the time

- Many of the conservatory scenes were filmed on location at the Moscow Conservatory, which stood in for the St. Petersburg Conservatory

- The film's portrayal of Rimsky-Korsakov's political troubles was carefully handled to align with Soviet ideological requirements of the time

- The musical arrangements in the film were supervised by conductor Gennady Rozhdestvensky, who would become one of the Soviet Union's most prominent conductors

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics praised the film for its faithful portrayal of the composer's life and its artistic merit, particularly noting Nikolai Cherkasov's performance as Rimsky-Korsakov. The film was celebrated in Soviet media as an exemplary work of socialist realism that successfully combined historical accuracy with ideological education. Western critics at Cannes noted the film's high production values and musical performances, though some observed that the political aspects of the narrative were presented in a manner consistent with Soviet ideological requirements. Modern film historians view the work as an important document of postwar Soviet cinema, representing both the artistic achievements and ideological constraints of the period. The film is now studied as an example of how Soviet biographical films negotiated the tension between historical accuracy and political messaging.

What Audiences Thought

The film was well received by Soviet audiences upon its release, particularly among educated viewers and music lovers who appreciated its attention to musical detail and historical authenticity. The film's musical performances were especially popular, with many viewers requesting recordings of the orchestral pieces featured in the movie. The film ran successfully in Soviet theaters for several months and was later re-released periodically, becoming a standard part of the Soviet cultural education curriculum. Among international audiences, the film found limited distribution but was appreciated by classical music enthusiasts and those interested in Russian culture. The film's popularity contributed to a renewed interest in Rimsky-Korsakov's works within the Soviet Union, leading to increased performances of his operas and orchestral pieces in concert halls across the country.

Awards & Recognition

- Stalin Prize (1953) - Second degree for Director Grigoriy Roshal and the production team

- Vasilyev Brothers State Prize of the RSFSR (1953) - For Nikolai Cherkasov's performance as Rimsky-Korsakov

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Earlier Soviet biographical films about cultural figures

- The tradition of literary adaptations in Russian cinema

- Soviet socialist realist aesthetic principles

- 19th-century Russian literary traditions

- European biographical film conventions of the 1940s

This Film Influenced

- Subsequent Soviet biographical films about composers

- Later Russian films about artistic figures

- Soviet musical biopics of the 1960s and 1970s

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved in the Gosfilmofond of Russia, the state film archive, and has undergone digital restoration as part of efforts to preserve classic Soviet cinema. Original negatives and prints are maintained in climate-controlled facilities, and the film has been transferred to modern digital formats for preservation and access. The restored version was released on DVD in the 2000s as part of a collection of classic Soviet biographical films.