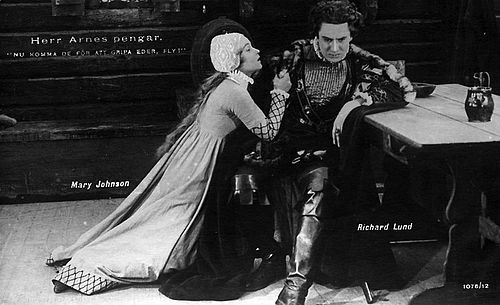

Sir Arne's Treasure

Plot

Set in 17th century Sweden during a harsh winter, the film follows three Scottish mercenaries led by Sir Archi who murder Sir Arne, a wealthy priest, and his entire household to steal a coffin filled with gold. The sole survivor is Elsalill, Sir Arne's foster daughter, who is taken in by relatives in the coastal town of Marstrand. There she falls deeply in love with a charming Scottish officer, unaware that he is Sir Archi, one of her family's murderers. When Elsalill discovers the truth through supernatural intervention—the ghost of her deceased sister appearing to her—she is torn between her love and her duty to justice. Ultimately, Elsalill sacrifices herself to ensure the murderers are brought to justice, and her body is carried away on an ice floe, creating a haunting visual metaphor for the film's themes of guilt, redemption, and the inexorable nature of fate.

About the Production

The film faced significant challenges during production, particularly in creating convincing winter scenes. Director Mauritz Stiller insisted on authentic atmosphere, leading to innovative techniques for simulating ice and snow. The production used salt and gypsum to create snow effects, and ice was manufactured in studio tanks. The famous ice floe sequence required elaborate mechanical setups and careful timing. The film's production took nearly six months, unusually long for the era, due to Stiller's perfectionism and the complex technical requirements of the winter sequences.

Historical Background

The film was produced in the immediate aftermath of World War I, during a period when Sweden, having remained neutral during the conflict, was experiencing cultural and economic growth. This era, often called the 'Golden Age of Swedish Cinema,' saw Swedish films gaining international recognition for their artistic quality and technical innovation. The film's themes of guilt, redemption, and supernatural justice resonated with post-war audiences grappling with the moral implications of the recent conflict. Sweden's neutrality had allowed its film industry to continue developing while European competitors were disrupted by the war. The film's success abroad helped establish Sweden as a major cinematic force and demonstrated that small nations could produce art of international significance. The adaptation of Lagerlöf's work also reflected a growing national pride in Swedish literature and culture.

Why This Film Matters

'Sir Arne's Treasure' represents a pinnacle of silent cinema artistry and helped establish the visual language of psychological horror films. Its influence extended far beyond Sweden, inspiring German Expressionist filmmakers and influencing the development of atmospheric cinema techniques. The film proved that literary adaptations could be both artistically ambitious and commercially successful, setting a precedent for future book-to-film adaptations. Its blend of historical drama and supernatural elements created a template for countless later films. The work also cemented Mauritz Stiller's reputation as one of cinema's early masters, leading to his invitation to Hollywood where he would later influence American cinema. The film's preservation and restoration in the late 20th century sparked renewed interest in silent cinema and helped preserve an important part of Swedish cultural heritage.

Making Of

The production of 'Sir Arne's Treasure' was marked by Mauritz Stiller's meticulous attention to detail and his innovative approach to visual storytelling. Stiller worked closely with cinematographer Julius Jaenzon to develop new techniques for capturing the bleak, beautiful winter landscapes that form the film's visual backbone. The famous ghost sequences required pioneering use of multiple exposure photography, with Jaenzon experimenting with various lighting and filter combinations to achieve the ethereal effects. The cast underwent extensive preparation, with Stiller insisting on method-like performances unusual for the silent era. The production design was equally ambitious, with full-scale sets built to replicate 17th century Swedish architecture. The ice floe sequence, where Elsalill's body is carried away, was particularly challenging, requiring a complex system of underwater tracks and carefully timed releases. The film's score, composed for live accompaniment, was created by Swedish musician Oskar Merikanto and became as famous as the film itself.

Visual Style

Julius Jaenzon's cinematography in 'Sir Arne's Treasure' is considered groundbreaking for its time and remains influential. The film's visual style is characterized by its stark, high-contrast lighting that creates dramatic shadows and highlights, anticipating the German Expressionist movement. Jaenzon employed innovative techniques for capturing winter landscapes, including specialized filters and exposure methods that emphasized the bleak beauty of snow and ice. The ghost sequences used pioneering double exposure techniques that created ethereal, translucent figures without visible technical artifacts. The cinematography makes extensive use of deep focus and careful composition to create layers of meaning within each frame. Jaenzon also developed new methods for shooting water and ice reflections, creating haunting visual motifs throughout the film. The camera work is remarkably fluid for the period, with tracking shots and movement that enhance the narrative's emotional impact.

Innovations

The film pioneered several technical innovations that would influence cinema for decades. The winter effects, created using a combination of salt, gypsum, and painted backdrops, were so convincing they set new standards for atmospheric cinematography. The ghost sequences featured some of the earliest successful uses of multiple exposure techniques for supernatural effects, creating seamless apparitions without visible matte lines. The production developed new methods for simulating ice and water movement, including mechanical systems that created realistic ice floe movement. The film's lighting techniques, particularly the use of high-contrast illumination to create psychological tension, anticipated the German Expressionist movement. The camera work included innovative tracking shots and unusual angles that enhanced the narrative's emotional impact. The production also experimented with color tinting, using blue tones for night scenes and amber for interior sequences to enhance mood and atmosphere.

Music

As a silent film, 'Sir Arne's Treasure' was originally accompanied by live musical performance. The official score was composed by Finnish-Swedish composer Oskar Merikanto, who created a romantic, atmospheric piece that emphasized the film's Nordic setting and emotional themes. The score utilized traditional Swedish folk melodies alongside original compositions, creating a distinctive musical identity. Different theaters employed various approaches to accompaniment, from full orchestras in major cinemas to single pianists in smaller venues. The music was carefully synchronized with the film's dramatic beats, with specific leitmotifs for characters and themes. Modern restorations have included newly commissioned scores by contemporary composers who have drawn on Merikanto's original themes while incorporating modern sensibilities. These new scores have helped introduce the film to modern audiences while maintaining its historical integrity.

Famous Quotes

"The dead do not rest until justice is done" (intertitle)

"Gold can buy many things, but not a clear conscience" (intertitle)

"Love knows no boundaries, not even between life and death" (intertitle)

"In the cold of winter, truth burns brightest" (intertitle)

"Some treasures are worth more than gold" (intertitle)

Memorable Scenes

- The opening murder sequence where the three Scottish mercenaries kill Sir Arne's household, shot with dramatic shadows and sudden violence that shocked 1919 audiences

- The first appearance of Elsalill's sister's ghost, achieved through revolutionary double exposure techniques that created an ethereal, translucent figure

- The winter landscape sequences with their stark, beautiful cinematography that established the film's atmospheric tone

- The confrontation scene where Elsalill discovers Sir Archi's true identity, featuring powerful close-ups and emotional intertitles

- The final ice floe sequence where Elsalill's body is carried away across the frozen sea, creating a haunting visual metaphor for the film's themes

- The ghost procession scene where multiple apparitions appear, showcasing the film's technical innovation in special effects

Did You Know?

- Based on the 1904 novel 'Herr Arnes pengar' by Nobel Prize-winning author Selma Lagerlöf, who was heavily involved in the adaptation process

- The film's winter cinematography was so realistic that many contemporary viewers believed it was actually filmed during winter, though most was shot using special effects

- Director Mauritz Stiller discovered and mentored Greta Garbo, casting her in his next film 'The Saga of Gosta Berling' after seeing her screen test

- The film was one of the first Swedish productions to achieve major international success, particularly in Germany and France

- The ghost effects were achieved using double exposure techniques that were groundbreaking for the time

- The original negative was thought lost for decades until a complete print was discovered in the 1970s in a German archive

- The film's success helped establish the 'Golden Age of Swedish Cinema' (1917-1924)

- Cinematographer Julius Jaenzon used specially modified cameras to capture the stark winter landscapes

- The film was banned in several countries for its violent content and supernatural themes

- Selma Lagerlöf was reportedly so pleased with the adaptation that she attended the premiere and praised Stiller's vision

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics hailed the film as a masterpiece of visual storytelling. The Swedish press praised its atmospheric cinematography and powerful performances, with Svenska Dagbladet calling it 'a triumph of Swedish art.' International critics were equally impressed; German publication Film-Kurier praised its 'unprecedented visual poetry,' while French critics noted its 'haunting beauty and psychological depth.' Modern critics continue to celebrate the film, with the British Film Institute describing it as 'one of the most artistically accomplished films of the silent era.' The film's reputation has grown over time, with many contemporary film scholars considering it Stiller's masterpiece and a crucial work in the development of cinematic language. Its restoration in the 1990s led to renewed critical appreciation, with The New York Times calling it 'a revelation of silent cinema's artistic possibilities.'

What Audiences Thought

The film was enormously popular with audiences upon its release, breaking box office records in Sweden and achieving significant success in international markets. Swedish audiences were particularly moved by the adaptation of Lagerlöf's beloved novel, with many attending multiple screenings. The film's emotional power and visual spectacle created word-of-mouth buzz that sustained its theatrical run for months. In Germany, where it was released as 'Herr Arnes Schatz,' it became one of the most popular foreign films of 1920. American audiences, though less familiar with the source material, responded to its universal themes and striking visuals. The film's success led to increased demand for Swedish films internationally and helped create a market for foreign art cinema in the United States. Even today, at revival screenings and film festivals, audiences respond strongly to its emotional intensity and visual beauty.

Awards & Recognition

- Best Foreign Film - Photoplay Magazine (1920)

- Best Artistic Production - Swedish Film Institute (retrospective award, 1949)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Selma Lagerlöf's novel 'Herr Arnes pengar'

- Swedish folklore and ghost stories

- German Romantic literature

- Nordic mythology

- Theatrical melodrama traditions

- Danish silent film aesthetics

- Literary naturalism

This Film Influenced

- The Phantom Carriage (1921)

- Nosferatu (1922)

- The Last Laugh (1924)

- Napoleon (1927)

- The Seventh Seal (1957)

- The Virgin Spring (1960)

- The Exorcist (1973)

- The Shining (1980)

- Let the Right One In (2008)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was believed lost for decades until a complete nitrate print was discovered in the German Federal Archives in the 1970s. This print underwent extensive restoration by the Swedish Film Institute in the 1990s, with digital restoration completed in 2015. The restored version preserves the original tinting and includes reconstructed intertitles based on surviving scripts and censorship records. The film is now preserved in the archives of the Swedish Film Institute, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and the British Film Institute. The restoration revealed details and visual effects that had been obscured in previous copies, leading to renewed appreciation of the film's technical achievements.