Tale of the Siberian Land

"A tale of love, sacrifice, and rebirth in the vast Siberian wilderness"

Plot

Andrei Balashov, a talented concert pianist, suffers a devastating hand wound during World War II that destroys his musical career and plunges him into deep depression. Feeling his life is meaningless without his art, Andrei flees Moscow and the woman he loves, Natasha, a rising opera singer, returning to his native Siberia. There, he finds work in a sawmill and begins to heal emotionally, entertaining his fellow workers with accordion music and discovering new purpose in manual labor and community. Meanwhile, Natasha's opera company is scheduled to tour America, but their plane experiences mechanical failure and makes an emergency landing near Andrei's Siberian village. The unexpected reunion forces both Andrei and Natasha to confront their feelings and the changes in their lives, leading to a powerful resolution about love, sacrifice, and finding meaning beyond one's chosen profession.

About the Production

Filming took place during challenging post-war conditions in the Soviet Union, with limited resources and strict government oversight. The production utilized actual Siberian locations for authenticity, though some scenes were shot at Mosfilm Studios in Moscow. Director Ivan Pyryev was known for his meticulous attention to detail and demanded multiple takes to achieve the emotional depth he desired. The film featured extensive musical sequences that required coordination between actors and professional musicians.

Historical Background

The film was produced during a critical period in Soviet history, just two years after the end of World War II, which had devastated the Soviet Union and resulted in approximately 27 million deaths. The post-war period was characterized by massive reconstruction efforts and Stalin's intensified control over cultural production. 'Tale of the Siberian Land' emerged during the early stages of the Cold War, when Soviet cinema was increasingly used as a tool of ideological propaganda and cultural diplomacy. The film's themes of personal sacrifice, the transformative power of labor, and the reconciliation between intellectuals and workers reflected the Soviet government's emphasis on national unity and rebuilding. The depiction of Siberia as a land of opportunity and rebirth was particularly significant, as the region was being developed for its natural resources and strategic importance. The film's optimistic tone and celebration of Soviet values contrasted sharply with the harsh realities of post-war life, including food shortages, housing crises, and political repression.

Why This Film Matters

'Tale of the Siberian Land' became one of the most culturally significant Soviet films of the late 1940s, representing the pinnacle of the socialist realist genre while incorporating elements of romantic melodrama and musical entertainment. The film's portrayal of the reconciliation between artistic intellectuals and manual laborers embodied key Soviet ideological principles about the unity of all social classes in building communism. Its success established a template for subsequent Soviet musical dramas that combined romantic storytelling with political messaging. The film's songs became part of the Soviet cultural canon, frequently performed on radio and at public gatherings. The romanticized image of Siberia presented in the film influenced popular perceptions of the region for generations and contributed to the myth of Siberia as a place of both exile and redemption. The film's international success at film festivals in Venice and Karlovy Vary demonstrated the Soviet Union's cultural ambitions during the early Cold War period. Its continued popularity through multiple re-releases indicates its resonance with Soviet audiences across different generations.

Making Of

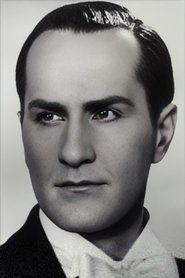

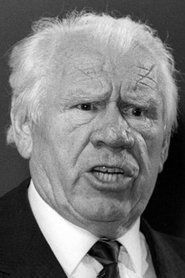

The production of 'Tale of the Siberian Land' was a massive undertaking in post-war Soviet cinema. Director Ivan Pyryev, already established as one of the USSR's premier filmmakers, approached this project with his characteristic blend of romanticism and socialist realism. The casting of Vladimir Druzhnikov as Andrei was particularly significant, as he had just returned from military service and could draw on authentic experiences of wartime trauma. Marina Ladynina, Pyryev's frequent collaborator and muse, underwent extensive vocal training for her role as the opera singer Natasha. The Siberian sequences presented enormous logistical challenges, as the crew had to transport equipment to remote locations during harsh weather conditions. The musical numbers were particularly complex, requiring coordination between the actors, professional musicians, and choreographers. Pyryev insisted on using real workers in the sawmill scenes to maintain authenticity, though this sometimes created conflicts with professional actors accustomed to more controlled environments. The film's post-production took nearly six months due to the intricate sound mixing required for the musical sequences and the need to meet strict state censorship requirements.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Grigory Aronov and Yuri Raizman employed sweeping panoramic shots of the Siberian landscape to emphasize both its beauty and its vastness, creating a visual contrast between the intimate human drama and the overwhelming power of nature. The film utilized innovative camera techniques for its time, including dramatic low-angle shots in the sawmill sequences that emphasized the dignity of manual labor. The Moscow sequences featured more conventional studio lighting and framing to represent the artificiality of Andrei's former life as a concert pianist. The airplane landing scene was particularly notable for its use of deep focus and wide-angle lenses to create a sense of both spectacle and vulnerability. The cinematography effectively supported the film's ideological message by presenting the Soviet landscape and its workers in heroic, almost mythic terms. The visual style evolved throughout the film, becoming more naturalistic and expansive as Andrei's character underwent his transformation in Siberia.

Innovations

The film was notable for its innovative use of location sound recording in the Siberian sequences, which was technically challenging given the equipment limitations of the time. The airplane scene required sophisticated special effects and miniature work that pushed the boundaries of Soviet technical capabilities. The film's sound design effectively contrasted the acoustics of concert halls with the industrial sounds of the sawmill, creating an auditory representation of Andrei's journey from elite artist to worker. The musical sequences featured early examples of multi-track recording techniques that allowed for richer sound textures in the musical numbers. The film's color sequences (though limited due to post-war film stock shortages) demonstrated advances in Soviet color cinematography. The production also developed new techniques for filming in extreme weather conditions, which influenced subsequent Soviet films shot in similar environments.

Music

The film's music was composed by Nikolai Kryukov, with additional songs by Soviet composers Tikhon Khrennikov and Vano Muradeli. The soundtrack blended classical piano pieces (representing Andrei's past life) with folk-inspired accordion music (symbolizing his connection to the people). Several songs from the film became major hits in the Soviet Union, particularly 'The Song of the Siberian Land' and 'Moscow Nights' (not to be confused with the more famous song of the same name). The musical numbers were carefully integrated into the narrative, serving both as entertainment and as commentary on the characters' emotional states. The film's orchestral score utilized leitmotifs to represent different characters and themes, with Andrei's piano theme gradually transforming into more folk-based arrangements as he adapted to life in Siberia. The soundtrack was released on vinyl records and sold millions of copies throughout the Soviet Union and Eastern Bloc countries. The music's success led to concert performances of the film's score by major Soviet orchestras.

Famous Quotes

When you lose your hands, you think you've lost everything. But when you find your heart, you realize you've found everything that matters.

Siberia doesn't just change you, it remakes you. The old you dies here, and a new one is born from the earth and the work.

Music isn't in the fingers, it's in the soul. Even if I can't play the piano anymore, I can still make music with my heart.

We left the cities thinking we were escaping our past, but we found our future in the sound of saws and the songs of workers.

Love doesn't need concert halls or spotlights. It needs only two hearts beating in the same rhythm, even if one beats with sorrow and the other with hope.

Memorable Scenes

- Andrei's emotional breakdown in the empty concert hall where he realizes he can no longer play piano, with the camera focusing on his bandaged hands trembling over the keys

- The sawmill sequence where Andrei first plays the accordion for his fellow workers, gradually winning them over with music that speaks to their struggles and hopes

- The dramatic airplane emergency landing in the Siberian wilderness, with Natasha watching in terror as the plane descends toward the unknown landscape

- The climactic reunion scene between Andrei and Natasha in the Siberian village, where both characters confront how much they've changed since their separation

- The final musical number where the entire community comes together in celebration, symbolizing the unity of workers and artists in building the new Soviet society

Did You Know?

- The film was one of the highest-grossing Soviet films of 1947, with approximately 25.8 million tickets sold in the USSR

- Director Ivan Pyryev married lead actress Marina Ladynina in 1954, though they had worked together on several films prior to their marriage

- The film's musical score became extremely popular, with several songs becoming standards in Soviet popular music

- Vladimir Druzhnikov had to learn to play the accordion convincingly for his role, despite being a classically trained actor rather than a musician

- The airplane scene was particularly challenging to film, as actual aircraft were scarce in post-war Soviet Union

- The film was re-released multiple times in the USSR throughout the 1950s and 1960s due to its enduring popularity

- Soviet leader Joseph Stalin reportedly praised the film for its positive portrayal of Soviet workers and the transformation of intellectuals through labor

- The sawmill scenes were filmed at an actual working facility, with real lumberjacks serving as extras

- The film's success led to a stage musical adaptation that toured throughout the Soviet Union

- Several scenes were cut from the original version during the brief period of anti-cosmopolitan campaigns in the late 1940s

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics praised the film as a masterpiece of socialist realism, with particular acclaim for Ivan Pyryev's direction and the performances of the lead actors. Official Soviet publications like Pravda and Iskusstvo Kino lauded the film's ideological clarity and emotional power. Western critics at the Venice Film Festival were more measured, acknowledging the film's technical polish and emotional appeal while noting its propagandistic elements. Modern film scholars have re-evaluated the work as a complex artifact of Soviet cinema, recognizing both its artistic merits within its ideological framework and its role in cultural diplomacy. Some contemporary critics have noted the film's surprising emotional depth beneath its political messaging, particularly in its treatment of trauma and recovery. The film's musical sequences have been analyzed as sophisticated examples of Soviet popular culture that successfully blended folk traditions with classical influences.

What Audiences Thought

The film was enormously popular with Soviet audiences, becoming one of the biggest box office successes of 1947. Viewers responded particularly strongly to the romantic storyline and the musical numbers, many of which became popular songs that were sung throughout the Soviet Union. The film's themes of personal redemption through labor resonated with audiences recovering from wartime trauma and participating in post-war reconstruction. Letters to Soviet newspapers from viewers praised the film's optimism and emotional sincerity. The relationship between Andrei and Natasha became one of the most celebrated screen romances in Soviet cinema history. The film's multiple re-releases throughout the 1950s and 1960s demonstrated its enduring appeal across different generations of Soviet viewers. Even decades after its release, the film remained a cultural touchstone, referenced in literature and popular culture as an example of classic Soviet cinema.

Awards & Recognition

- Stalin Prize (First Degree) - 1948

- Best Director Award at the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival - 1948

- Best Actress Award (Marina Ladynina) at the Venice Film Festival - 1948

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Socialist realist literature of the 1930s and 1940s

- Classical Russian literature (particularly works about redemption and transformation)

- Soviet musical theater traditions

- Earlier Pyryev films featuring similar themes and cast members

- Hollywood musical dramas (adapted for Soviet ideological purposes)

This Film Influenced

- Cossacks of the Kuban (1949) - also directed by Pyryev with Ladynina

- The Kuban Cossacks (1950) - similar themes of agricultural workers

- The Communist (1957) - similar themes of ideological transformation

- Later Soviet musical dramas of the 1950s and 1960s

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved in the Gosfilmofond Russian State Archive of Film and Photo Documents. A restored version was released in the 1970s, and a digital restoration was completed in 2015 as part of the Mosfilm Classic Collection restoration project. The original camera negative has been maintained in climate-controlled facilities, ensuring the film's preservation for future generations. Several different versions exist, including the original theatrical release and slightly edited versions for international distribution.