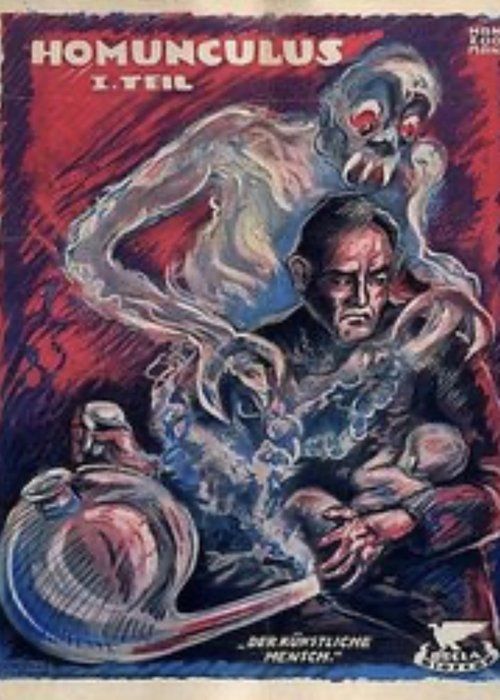

The Artificial Man

"The Creature Without a Soul Seeks Vengeance on Mankind"

Plot

Dr. Kühne, a brilliant but morally ambiguous scientist, successfully creates an artificial man in his laboratory through advanced scientific methods. The creature, named Homunculus, is physically perfect and intellectually superior to ordinary humans, but lacks a soul and the capacity for genuine emotion or love. Upon discovering his artificial origins and spiritual emptiness, Homunculus turns against his creator and humanity, using his superior abilities to instigate revolutions and chaos across society. He becomes a beautiful but monstrous tyrant, manipulating world events while being relentlessly pursued by Dr. Kühne, who seeks to rectify his terrible mistake and either destroy or redeem his creation. The tragic arc follows Homunculus's journey from innocent artificial being to vengeful god-like figure, exploring themes of scientific hubris, the nature of humanity, and the consequences of playing God.

About the Production

Filmed during the height of World War I, the production faced significant challenges including material shortages and military conscription of crew members. The film was shot as a six-part serial, with each episode building upon the last to create an epic narrative. The elaborate laboratory sets were considered groundbreaking for their time, featuring complex electrical equipment and scientific apparatus that emphasized the film's modern scientific themes. Director Otto Rippert employed innovative camera techniques including tracking shots and dramatic lighting to enhance the supernatural and psychological elements of the story.

Historical Background

Homunculus was produced during a pivotal moment in German history, amid the devastation of World War I. The film's themes of artificial creation, scientific hubris, and social revolution resonated deeply with a German society experiencing unprecedented technological advancement alongside catastrophic destruction. The serial format allowed for extended exploration of contemporary anxieties about the nature of humanity in an age of industrial warfare and scientific progress. The film's production occurred during the early golden age of German cinema, when the industry was expanding rapidly despite wartime constraints. Its success demonstrated the power of cinema as both entertainment and social commentary, establishing patterns that would influence the later German Expressionist movement. The film's vision of an artificial being questioning its place in society reflected broader philosophical debates about modernity, technology, and human nature that were central to early 20th-century European intellectual discourse.

Why This Film Matters

Homunculus occupies a crucial position in cinema history as one of the earliest comprehensive explorations of the artificial being theme in film. Its influence extends far beyond its immediate success, directly inspiring later masterpieces like Metropolis (1927) and establishing narrative and visual tropes that would define science fiction cinema for decades. The film's portrayal of a scientifically created being grappling with questions of identity and purpose created a template for countless subsequent works exploring similar themes. Its success during wartime demonstrated cinema's power to address profound philosophical questions while providing mass entertainment. The film's aesthetic innovations, particularly its use of lighting and set design to create psychological atmosphere, contributed significantly to the development of German Expressionist cinema. Homunculus also represents an early example of transmedia influence, with its impact extending beyond cinema to fashion, literature, and popular culture in wartime Germany.

Making Of

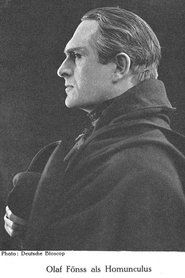

The production of Homunculus was a massive undertaking for the German film industry during wartime. Director Otto Rippert, working with cinematographer Carl Hoffmann, created a visually stunning epic that pushed the boundaries of early cinema. The laboratory sequences were particularly ambitious, requiring the construction of elaborate sets with working electrical equipment. Olaf Fønss underwent extensive preparation for the role, studying scientific literature and developing a distinctive physical presence that conveyed both the beauty and menace of the artificial man. The film's success led to increased investment in German science fiction productions, establishing a foundation for the later Expressionist movement. The production team faced constant challenges due to wartime restrictions, including rationing of film stock and the loss of key personnel to military service. Despite these obstacles, the film's technical achievements, particularly its use of lighting and special effects, set new standards for European cinema.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Carl Hoffmann was revolutionary for its time, employing innovative techniques to create visual metaphors for the film's themes. Hoffmann used dramatic lighting contrasts to emphasize the dual nature of the Homunculus character - beautiful yet monstrous, human yet artificial. The laboratory sequences featured complex lighting setups using multiple light sources to create an otherworldly atmosphere. Tracking shots and dynamic camera movements were employed to convey the sense of scientific progress and the Homunculus's superior abilities. The film's visual style incorporated elements that would later become hallmarks of German Expressionism, including distorted perspectives and symbolic use of light and shadow. Hoffmann's work demonstrated sophisticated understanding of visual storytelling, using cinematography not just to record action but to convey psychological states and thematic concerns.

Innovations

Homunculus featured several technical innovations that were groundbreaking for 1916. The film's special effects, particularly in the laboratory sequences, used real electrical equipment and early forms of practical effects to create convincing scientific experiments. The production employed advanced makeup techniques to transform Olaf Fønss into the artificial being, creating a look that was both beautiful and unsettling. The film's set design incorporated moving parts and mechanical elements that enhanced the sense of scientific achievement. The serial format itself was technically innovative, requiring consistent visual style and narrative continuity across multiple episodes filmed over an extended period. The film's use of lighting to create psychological atmosphere represented a significant advancement in cinematic technique, influencing the later development of German Expressionist visual style.

Music

As a silent film, Homunculus would have been accompanied by live musical performance during theatrical screenings. The original score was likely composed by Giuseppe Becce, a prominent film composer of the era who worked on many German productions. The music would have featured dramatic orchestral arrangements to enhance the scientific themes and emotional moments of the story. Specific musical motifs would have been developed for the Homunculus character, reflecting his artificial nature and inner conflict. The score would have incorporated contemporary musical styles while also using experimental elements to suggest the scientific and supernatural aspects of the narrative. Unfortunately, no written records of the original musical accompaniment survive, as was common for films of this period.

Famous Quotes

I am the perfect man, yet I possess no soul - this is my curse and my weapon against humanity

You created me without a heart, Doctor Kühne, and now I shall break the hearts of all mankind

Science has given me life, but only revenge can give me purpose

I am the future of humanity - beautiful, intelligent, and utterly without compassion

Memorable Scenes

- The laboratory creation sequence where Dr. Kühne successfully brings the Homunculus to life using electrical equipment and scientific apparatus

- The moment when Homunculus discovers his artificial nature and confronts his creator in a dramatic confrontation

- The revolutionary scenes where Homunculus uses his superior abilities to manipulate crowds and instigate social upheaval

- The final pursuit sequence through the streets of Berlin as Dr. Kühne hunts his creation to rectify his mistake

Did You Know?

- Homunculus was the most popular film serial in Germany during World War I, even influencing Berlin fashion trends with its distinctive costumes and visual style

- The film's success was so immense that star Olaf Fønss became one of the highest-paid actors in Europe, earning 100,000 marks for his performance

- The character of Homunculus influenced the creation of later artificial beings in cinema, including the iconic robot in Metropolis (1927)

- Despite being made during wartime, the film was exported internationally and achieved success in neutral countries like Denmark and Sweden

- The laboratory scenes featured real electrical equipment and Tesla coils, creating authentic special effects that amazed contemporary audiences

- The film's theme of an artificial being questioning its existence predates similar explorations in Blade Runner (1982) and A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001) by decades

- Director Otto Rippert was a former actor who had appeared in early German films before transitioning to directing

- The serial format was innovative for its time, creating one of the first cinematic franchises with a continuous narrative arc

- The film's political themes of revolution and social upheaval resonated strongly with German audiences during the war years

- Only fragments of the original six-part serial survive today, making it one of the most sought-after lost films of the German Expressionist era

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised Homunculus as a groundbreaking achievement in German cinema, with particular acclaim for Olaf Fønss's performance and the film's technical innovations. Film journals like Der Kinematograph and Lichtbild-Bühne hailed it as a masterpiece of scientific romance, noting its sophisticated exploration of philosophical themes. Critics were impressed by the film's ambitious scope and its successful blending of entertainment with intellectual depth. The serial format was particularly praised for allowing complex character development across multiple episodes. Modern critics and film historians recognize Homunculus as a crucial missing link in the development of early science fiction cinema and a significant precursor to German Expressionism. Despite its fragmented survival, the film is studied for its innovative narrative techniques and its role in establishing artificial intelligence as a central theme in cinema.

What Audiences Thought

Homunculus was a phenomenal commercial success, becoming the most popular film serial in Germany during World War I. Audiences were captivated by the story of the artificial man and flocked to theaters for each new installment. The film's popularity was such that it influenced fashion trends in Berlin, with viewers imitating the distinctive costumes and hairstyles worn in the movie. The character of Homunculus became a cultural phenomenon, with newspapers and magazines featuring discussions about the philosophical questions raised by the film. The serial's success continued even after the war, with the film being exported to other European countries where it found similar enthusiastic reception. Audience reaction was particularly strong to the film's blend of scientific speculation with emotional drama, creating a new type of cinematic experience that appealed to both intellectuals and general moviegoers.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Frankenstein by Mary Shelley

- The Golem legends

- Der Golem (1914 film)

- Alraune (1918)

- Contemporary German scientific and philosophical writings on artificial life

This Film Influenced

- Metropolis (1927)

- Frankenstein (1931)

- The Bride of Frankenstein (1935)

- Alraune (1928)

- Der Golem (1920)

- Blade Runner (1982)

- A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Unfortunately, Homunculus is considered a partially lost film. Only fragments from various episodes of the original six-part serial survive, scattered across different film archives including the Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv in Berlin and the Danish Film Institute. Some complete episodes may exist in private collections or smaller archives, but no complete version of the entire serial is known to survive. The surviving fragments have been partially restored and are occasionally screened at film festivals and special retrospectives of early German cinema. The film's status as a partially lost masterpiece makes it one of the most sought-after missing films from the German silent era.