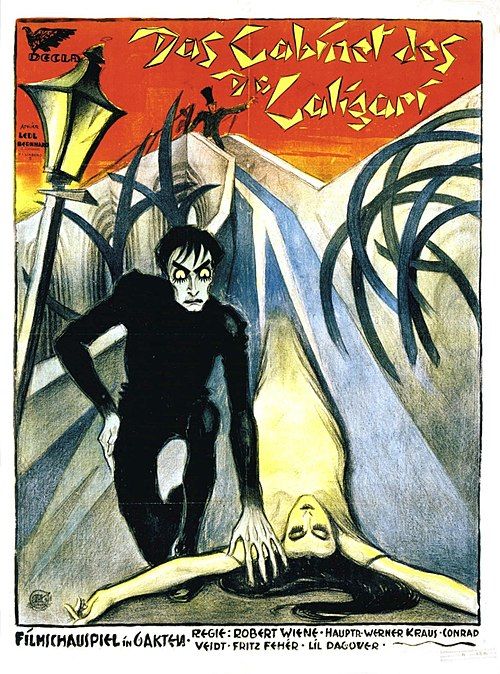

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari

"Du musst Caligari werden! (You must become Caligari!)"

Plot

In a frame narrative set in an asylum garden, Francis recounts to a fellow visitor the disturbing tale of how his life was shattered by the mysterious Dr. Caligari. When Francis and his friend Alan visit a local fair, they encounter the sinister Dr. Caligari exhibiting his somnambulist Cesare, who has been asleep for 23 years but can be awakened to predict the future. After Cesare predicts Alan's death, which comes true the next day, Francis launches an investigation into Caligari, leading to a series of murders and the abduction of Francis's fiancée Jane. The film culminates in a shocking twist when the frame story reveals that Francis is actually an asylum patient, and his entire narrative is a delusion - the doctors and staff are the real people he has transformed into characters from his psychosis.

About the Production

The film's revolutionary expressionistic sets were designed by Hermann Warm, Walter Reimann, and Walter Röhrig, who came from the expressionist art movement. Sets were constructed from painted canvas with distorted perspectives, jagged angles, and artificial shadows painted directly onto the surfaces. Director Robert Wiene insisted on this stylized approach to externalize the characters' psychological states. The film was shot in only six to seven weeks during the winter of 1919-1920, with the cast working long hours in the uncomfortable, cramped sets. The famous twist ending was not in the original script by Hans Janowitz and Carl Mayer but was added by producer Erich Pommer and Fritz Lang to make the film more commercially acceptable.

Historical Background

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari emerged during the turbulent Weimar Republic period, following Germany's devastating defeat in World War I and the subsequent social, political, and economic chaos. The film reflects the pervasive sense of disorientation, mistrust of authority, and psychological trauma that characterized German society during this time. The expressionistic style mirrored the broader artistic movement that sought to externalize internal emotional states rather than depict reality objectively. The film's themes of madness, manipulation, and the abuse of authority resonated deeply with a German population struggling to make sense of their recent history and uncertain future. Made during the hyperinflation crisis, the film's production occurred in an environment of extreme artistic freedom but material scarcity, conditions that paradoxically fostered incredible creativity in German cinema. The film's international success helped establish German cinema as a major cultural force in the post-war period.

Why This Film Matters

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is arguably one of the most influential films in cinema history, establishing visual and narrative techniques that would resonate for decades. It essentially created the visual language of psychological horror and film noir, with its use of distorted sets, dramatic shadows, and subjective reality. The film's expressionistic style influenced countless directors, including Alfred Hitchcock, Tim Burton, and Martin Scorsese. Its twist ending revolutionized narrative cinema and predates similar devices in films like The Sixth Sense by nearly 80 years. The film's exploration of madness and unreliable narration influenced the entire psychological thriller genre. In terms of art cinema, it demonstrated how film could transcend mere entertainment to become a serious artistic medium, paving the way for the auteur theory. The film's visual aesthetic has been referenced in music videos, comic books, and fashion, making it one of the most recognizable silent films in popular culture. It also helped establish horror as a legitimate film genre rather than mere exploitation fare.

Making Of

The production was marked by intense creative conflicts between the writers, who wanted a straightforward anti-authoritarian story, and the producers, who demanded the frame story to soften the political message. Directors Fritz Lang and Ernst Lubitsch were initially considered before Robert Wiene was chosen. The set designers, all members of the Berlin avant-garde art scene, rejected realistic sets in favor of painted canvases that reflected the characters' psychological states. The actors had to adapt their performances to match the stylized environment, with Werner Krauss creating an exaggerated, jerky movement style for Caligari and Conrad Veidt developing a fluid, almost mechanical grace for Cesare. The film was shot during a period of severe economic hardship in post-WWI Germany, with the cast and crew working for minimal wages in unheated studios. The famous scene where Cesare carries Jane through the distorted town required Veidt to carry Lil Dagover for hours while navigating the deliberately treacherous set design.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Willy Hameister and Hermann Kirchhoff was revolutionary for its time, employing techniques that directly supported the film's expressionistic vision. The camera work featured unusual angles and compositions that mirrored the distorted sets, creating a cohesive visual language of psychological unease. The cinematographers used dramatic lighting effects, with harsh contrasts and deep shadows that prefigured the film noir style. Many shots were composed to emphasize the jagged, unnatural lines of the sets, with characters often positioned at odd angles to enhance the sense of disorientation. The camera movement was deliberately limited, with static shots that forced viewers to confront the bizarre environments head-on. The use of iris shots and other optical effects helped create a dreamlike, nightmarish quality. The black and white photography was enhanced by tinting in original release prints, with different scenes colored to enhance their emotional impact - blue for night scenes, amber for daylight, and red for moments of violence or passion.

Innovations

The film's most significant technical achievement was its revolutionary approach to production design, which essentially created a new visual language for cinema. The painted sets with their distorted perspectives and artificial shadows represented a complete departure from the realistic sets that dominated cinema of the era. The film pioneered the use of mise-en-scène to externalize psychological states, a technique that would influence countless future films. The innovative use of lighting, with shadows painted directly onto sets, created a controlled visual environment impossible to achieve with natural lighting alone. The film's narrative structure, with its frame story and unreliable narrator, was groundbreaking for its time and influenced the development of psychological thrillers. The makeup and costume design, particularly for Cesare, created iconic looks that would influence horror character design for decades. The film's success demonstrated that cinema could be a medium for serious artistic expression, helping elevate the status of film from popular entertainment to art form.

Music

As a silent film, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari was originally accompanied by live musical performances that varied by theater and region. The original German score was composed by Giuseppe Becce, though many theaters used their own arrangements of classical music. The music was crucial to establishing the film's atmosphere, with dissonant chords and minor keys reflecting the psychological tension. Modern restorations have featured new scores by various composers, including Timothy Brock, who created a faithful reconstruction of the original 1920s style, and more contemporary interpretations by electronic artists. The 2014 restoration featured a score by the Alloy Orchestra that used both period-appropriate instruments and modern techniques to bridge historical authenticity with contemporary sensibilities. The absence of dialogue actually enhanced the film's universal appeal, allowing the visual storytelling and musical accompaniment to create a purely cinematic experience that transcended language barriers.

Famous Quotes

I must know everything. I must penetrate the heart of his secret!

Sleep in death-like sleep... Cesare, can you hear me? Awaken!

You must become Caligari!

I know that Cesare will answer my question!

He has been sleeping for twenty-three years. Now I will awaken him.

Tomorrow you will die!

These are not the confessions of a madman, but the revelations of a soul tormented by injustice.

I am Caligari!

Memorable Scenes

- The opening scene in the distorted asylum garden where Francis begins his story, immediately establishing the film's expressionistic visual style and framing device

- Cesare's dramatic awakening from his death-like sleep, with Werner Krauss as Caligari commanding him to rise while the audience sees the somnambulist's eyes snap open

- The murder sequence where Cesare stalks Alan through the twisted, angular streets, with shadows painted on walls creating a maze of psychological terror

- The scene where Cesare abducts Jane, carrying her through the impossible architecture of the town while villagers pursue him through the distorted landscape

- The final revelation in the asylum where the camera pulls back to show the reality of the situation, transforming the entire narrative into Francis's delusion

Did You Know?

- The film was inspired by a real-life experience of writer Hans Janowitz, who was allegedly mistreated by a military psychiatrist during World War I

- Conrad Veidt as Cesare had to wear heavy makeup and was required to perform his own stunts, including climbing a ladder while in a hypnotic trance

- The film's sets were deliberately designed to have no right angles to create a sense of unease and madness

- The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari was one of the first films to use a twist ending, a device that would become commonplace in cinema

- Despite being a German film, it was initially more successful in Japan and the United States than in Germany

- The original script ended with Caligari being captured and institutionalized, revealing him as the mad one, not Francis

- The film's title was inspired by a sideshow attraction at the Berlin Wintergarten called 'The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari'

- Werner Krauss, who played Caligari, was so convincing in the role that audiences often believed he was actually insane

- The film was banned in several countries for its 'subversive' content and potential to incite madness

- The expressionistic style was so influential that it created an entire genre of German Expressionist cinema

What Critics Said

Initial critical reception was mixed but generally positive, with many critics praising its visual innovation while questioning its narrative coherence. German critics of the time were divided, with some calling it 'a masterpiece of German film art' while others dismissed it as 'confused and meaningless.' International critics were more uniformly appreciative, with American publications calling it 'the most remarkable film ever produced' and 'a work of genius.' By the 1940s, film critics like Siegfried Kracauer had reinterpreted the film as an allegory for the rise of authoritarianism in Germany. Modern critics universally acclaim the film; it holds a 98% rating on Rotten Tomatoes and is regularly included in lists of the greatest films ever made, including Sight & Sound's prestigious decennial poll. Contemporary critics praise its revolutionary visual style, psychological depth, and enduring influence on cinema.

What Audiences Thought

Contemporary audiences were both fascinated and disturbed by the film's unconventional style and dark themes. The film was a commercial success in Germany and particularly popular in France, Japan, and the United States, where it played for extended runs in major cities. Some audience members reportedly fainted during screenings due to the intense psychological impact, while others were so intrigued they attended multiple times to understand the complex narrative. The film's word-of-mouth reputation as a shocking and innovative experience helped drive attendance. In the decades following its release, it developed a cult following among film enthusiasts and art house audiences. Modern audiences, particularly those interested in film history and horror, continue to be drawn to its unique aesthetic and psychological complexity, with restored versions regularly playing in revival cinemas and film festivals.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- German Expressionist art movement

- Edvard Munch's paintings

- The works of Franz Kafka

- Sigmund Freud's psychoanalytic theories

- Post-WWI German literature

- Gothic literature tradition

- Sideshow and carnival culture of the early 20th century

This Film Influenced

- Nosferatu (1922)

- Metropolis (1927)

- M (1931)

- The Third Man (1949)

- Psycho (1960)

- Blade Runner (1982)

- Batman (1989)

- The Matrix (1999)

- The Sixth Sense (1999)

- Shutter Island (2010)

- Inception (2010)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is well-preserved with multiple versions existing in archives worldwide. The most complete version is held at the Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv in Berlin. The film has undergone several restorations, most notably in 2014 by the Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau Foundation, which used elements from various international copies to create the most complete version possible. Some scenes remain lost, particularly from the original German release, but the film is essentially intact and viewable. The film entered the public domain in many countries, which has both helped its preservation through wide distribution and complicated restoration efforts due to the proliferation of inferior copies. The 2014 restoration was scanned in 2K resolution from the best available elements and features tinting that approximates the original release colors.