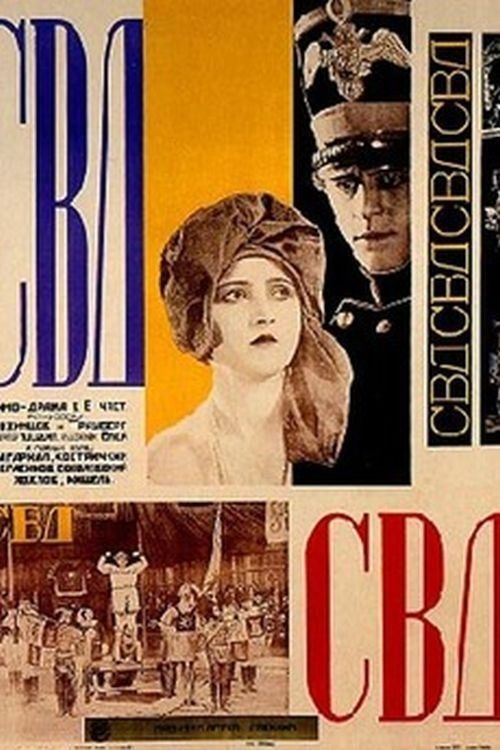

The Club of the Big Deed

Plot

Set in the tense atmosphere preceding the Decembrist Revolt of 1825, the film follows a mysterious chevalier of fortune who arrives in southern Russia seeking to make the ultimate wager. As he consults his cards to determine on whom to place his bet, the film weaves together multiple storylines of conspirators, aristocrats, and revolutionaries all making fateful choices. The narrative explores the psychological tension and moral ambiguity of those involved in the uprising against Tsarist autocracy. Through its elliptical storytelling and symbolic imagery, the film captures the feverish anticipation and uncertainty of a society on the brink of transformation. The chevalier's game becomes a metaphor for the larger gamble being taken by the Decembrists, risking everything for their vision of Russia's future.

About the Production

The film was a collaborative effort between Grigori Kozintsev and Leonid Trauberg, though only Kozintsev is credited as director. It was produced during their early period with the FEKS collective, which emphasized eccentric performance styles and innovative visual techniques. The production faced challenges typical of early Soviet cinema, including limited resources and political scrutiny of content dealing with revolutionary themes. The film's treatment of the Decembrist revolt was particularly sensitive as it touched on themes of rebellion against authority, requiring careful navigation of Soviet censorship.

Historical Background

Produced in 1927, 'The Club of the Big Deed' emerged during a crucial period in Soviet cultural history known as the NEP (New Economic Policy) era, when relative artistic freedom coexisted with increasing state control. The film's focus on the Decembrist Revolt of 1825 was particularly resonant in 1920s Soviet Union, as the Bolsheviks sought to legitimize their revolution by connecting it to earlier Russian revolutionary traditions. The mid-1920s saw a flourishing of avant-garde cinema in the Soviet Union, with directors like Eisenstein, Pudovkin, and Vertov pioneering new cinematic techniques. This film was part of a broader cultural project to create a new Soviet art that would be both revolutionary in content and innovative in form. The period also saw intense debates about the role of cinema in building socialism, with theorists like Eisenstein arguing for cinema as a tool for ideological education. The film's production coincided with the tenth anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution, a time of reflection on revolutionary history and its meaning for contemporary Soviet society.

Why This Film Matters

The film holds an important place in Soviet cinema history as an early example of the historical-revolutionary genre that would become a staple of Soviet filmmaking. It represents the artistic vision of the FEKS collective, which sought to combine theatrical eccentricity with cinematic innovation to create a distinctly Soviet art form. The film's approach to depicting revolutionary history influenced subsequent Soviet historical films, establishing conventions for how revolutionary events were portrayed on screen. Its experimental visual techniques and editing style contributed to the development of Soviet montage theory and practice. The film also reflects the complex relationship between art and politics in early Soviet culture, demonstrating how filmmakers navigated the demands of ideological content while pursuing artistic innovation. Though less well-known internationally than the works of Eisenstein or Pudovkin, it represents an important alternative current in 1920s Soviet cinema that emphasized theatricality and eccentric performance over formalist montage.

Making Of

The making of 'The Club of the Big Deed' represents a fascinating chapter in early Soviet cinema history. Kozintsev and Trauberg, working within the FEKS collective, sought to create a new cinematic language that combined theatrical eccentricity with revolutionary themes. The production involved extensive historical research into the Decembrist period, with the directors consulting historical documents and visiting actual locations associated with the revolt. The cast, many of whom were FEKS members, underwent intensive training in physical expression and gesture work essential for silent film performance. The film's distinctive visual style was achieved through innovative camera techniques, including unusual angles and dynamic movement that emphasized the psychological states of the characters. The production team faced significant challenges in recreating 1820s Russia with limited resources, often having to improvise costumes and props from available materials. The film's editing was particularly groundbreaking, employing rapid montage sequences to create emotional and political impact.

Visual Style

The cinematography, likely handled by Andrei Moskvin or other prominent Soviet cameramen of the period, employed innovative techniques characteristic of 1920s Soviet avant-garde cinema. The visual style combined elements of German Expressionism with Soviet constructivist aesthetics, creating a distinctive look that emphasized the psychological tension of the narrative. Dynamic camera movements and unusual angles were used to convey the emotional states of characters and the revolutionary fervor of the period. The lighting design featured dramatic contrasts between light and shadow, creating a mood of conspiracy and impending revolt. The film's composition often placed characters within architectural spaces that symbolized their social positions and psychological constraints. The cinematography also incorporated documentary-like shots of historical locations, blending realistic detail with expressionistic stylization.

Innovations

The film demonstrated several technical innovations characteristic of 1920s Soviet cinema, particularly in its use of montage editing to create dramatic and psychological effects. The editing techniques employed rapid cutting and juxtaposition of images to convey meaning and emotion, following principles developed by Eisenstein and other Soviet theorists. The film also experimented with superimposition and multiple exposure techniques to create symbolic imagery and represent characters' psychological states. The production made innovative use of location shooting, combining authentic historical settings with studio work to create a convincing representation of 1820s Russia. The film's special effects, while modest by modern standards, were sophisticated for their time and effectively served the narrative's symbolic and dramatic needs.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Club of the Big Deed' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The score would likely have been compiled from classical pieces and original compositions by Soviet musicians, reflecting the dramatic and revolutionary themes of the film. The musical accompaniment would have varied between different theaters, as was common practice for silent films of the period. The score would have emphasized the tension and drama of key scenes, particularly those depicting the conspiracy and the approaching revolt. Music would have been used to underscore the psychological states of characters and to highlight the film's revolutionary themes. No original score survives, as was typical for silent films of this era.

Famous Quotes

No documented quotes survive from this partially lost silent film

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence where the chevalier consults his cards, establishing the film's central metaphor of gambling with history

- The conspirators' secret meeting where plans for the revolt are discussed, using innovative lighting to create an atmosphere of tension and secrecy

- The climactic montage sequence depicting the approach of the revolt, combining documentary imagery with dramatic reenactment

Did You Know?

- The film was co-directed by Leonid Trauberg, though he is often uncredited in official records

- It was one of the earliest films to depict the Decembrist Revolt, a pivotal event in Russian revolutionary history

- The film is considered lost or partially lost, with only fragments surviving in Russian film archives

- The title 'Club of the Big Deed' refers to a secret society of conspirators planning the revolt

- The film employed innovative editing techniques influenced by Eisenstein's montage theory

- Pyotr Sobolevsky, who starred in the film, later became a prominent Soviet character actor

- The film was part of a series of historical-revolutionary films produced by Sovkino in the 1920s

- The chevalier character was based on composite historical figures from the period

- The film's visual style was heavily influenced by German Expressionism and Soviet constructivism

- It was one of the last silent films produced before the transition to sound in Soviet cinema

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics praised the film for its innovative approach to historical material and its dynamic visual style, though some criticized its excessive theatricality and departure from realist traditions. The film was noted for its successful integration of FEKS performance techniques with cinematic storytelling. Critics particularly appreciated the film's treatment of the Decembrist theme, seeing it as an important contribution to Soviet historical cinema. In later years, film historians have recognized the movie as an significant though often overlooked work in the Soviet silent film canon, noting its experimental qualities and its role in the development of Kozintsev and Trauberg's directorial style. Modern scholars have reevaluated the film as an important example of how early Soviet cinema dealt with revolutionary history and as a key work in the FEKS collective's output.

What Audiences Thought

The film received moderate attention from Soviet audiences upon its release in 1927, with viewers particularly responding to its dramatic portrayal of the Decembrist conspiracy and its dynamic visual presentation. The eccentric performance style employed by the actors, while sometimes confusing to audiences accustomed to more realistic acting, was appreciated by younger viewers seeking new forms of artistic expression. The film's historical subject matter resonated with Soviet audiences' interest in revolutionary history, though some found its elliptical narrative structure challenging to follow. The movie was part of a broader cultural education effort in the 1920s to familiarize Soviet citizens with key moments in revolutionary history, and it served this purpose effectively despite its artistic experimentation.

Awards & Recognition

- None documented - Soviet film awards system not yet established in 1927

Film Connections

Influenced By

- German Expressionist cinema

- Soviet montage theory

- FEKS theatrical techniques

- Historical-revolutionary literature

- Works of Alexander Pushkin

- French revolutionary drama

This Film Influenced

- The New Babylon

- 1929

- ,

- October

- 1928

- ,

- Other Soviet historical-revolutionary films of the late 1920s

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is considered partially lost, with only fragments surviving in the Gosfilmofond archive in Russia. Some sequences may exist in private collections or other archives, but a complete version is not known to survive. Efforts to locate and preserve remaining footage continue by Russian film preservationists.