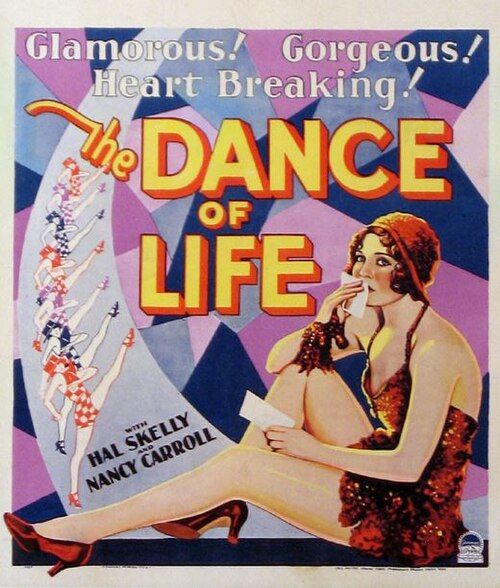

The Dance of Life

"The Story of Vaudeville... of Love... and of Broadway!"

Plot

Ralph 'Skippy' Crawford is a struggling vaudeville comic whose career is going nowhere, while Bonnie King is a talented but equally unsuccessful dancer. After meeting at a cheap boarding house, they decide to combine their talents and form a comedy-dance act. To save money on tour expenses, they enter into a marriage of convenience, though they initially maintain a professional distance. Their act gradually gains popularity, eventually landing them a coveted spot on Broadway, where they become a sensation. As their professional success grows, so do their genuine feelings for each other, but Skippy's newfound fame leads to arrogance and infatuation with a wealthy socialite, threatening both their marriage and their partnership.

About the Production

The Dance of Life was one of Paramount's early all-talking pictures, filmed during the challenging transition from silent to sound cinema. The production featured elaborate musical numbers and vaudeville sequences that required complex audio recording setups. The film was based on the popular Broadway play 'Burlesque' by George Manker Watters and Arthur Hopkins, which had been a hit starring Barbara Stanwyck. The transition from stage to screen required significant adaptation to accommodate the new sound technology while maintaining the theatrical energy of the original production.

Historical Background

The Dance of Life was produced during a pivotal moment in cinema history - the transition from silent films to talkies. 1929 was the year when sound cinema definitively took over Hollywood, with studios scrambling to convert their facilities and retrain their personnel. The Great Depression was beginning to take hold, making escapist entertainment like musicals particularly valuable to audiences seeking relief from economic hardship. The film's focus on vaudeville reflected nostalgia for a dying art form, as vaudeville theaters were rapidly closing due to the competition from movies. The Broadway setting also capitalized on the public's fascination with theater life, which would become a popular genre throughout the 1930s. The film's production coincided with the establishment of the Academy Awards' second year, as the industry was creating institutions to recognize and standardize cinematic excellence.

Why This Film Matters

As one of the earliest successful backstage musicals, 'The Dance of Life' helped establish a template for countless films that would follow. It demonstrated how the new sound technology could enhance musical performances and create more immersive entertainment experiences. The film's exploration of show business romance and the price of fame became recurring themes in Hollywood cinema. Its success proved that audiences were hungry for musical content, leading to a flood of musical productions in the early 1930s. The movie also captured the transition from vaudeville to modern entertainment, preserving the spirit of an American theatrical tradition that was rapidly disappearing. Nancy Carroll's performance helped establish the archetype of the plucky, talented showgirl who would become a staple of 1930s cinema.

Making Of

The production of 'The Dance of Life' faced numerous challenges typical of early sound films. The recording equipment was cumbersome and limited camera movement, forcing director John Cromwell to adapt his visual style. The cast had to be carefully selected not just for their acting ability but for their voice quality and singing talent. Hal Skelly's vaudeville background proved invaluable during the musical sequences, as he understood the timing and rhythm needed for live performance. The marriage scenes between Skelly and Nancy Carroll were particularly challenging to film, as the early sound technology required actors to stand relatively still near microphones, limiting their physical interaction. The Broadway sequences were filmed on elaborate sets that recreated the theater district atmosphere, with hundreds of extras and complex choreography that had to be synchronized with the music recording.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Victor Milner had to adapt to the limitations of early sound recording equipment. The camera movements were more restricted than in silent films, but Milner compensated with creative lighting and composition. The vaudeville sequences featured dynamic staging that captured the energy of live performance, while the more intimate scenes used softer lighting to emphasize the romantic elements. The Broadway numbers were shot with multiple cameras to capture different angles of the elaborate choreography, a technique that was becoming standard for musical productions. The black and white photography used high contrast lighting to create the theatrical atmosphere of backstage life.

Innovations

The Dance of Life showcased several technical innovations for its time. Paramount used their newly developed sound-on-film system, which provided better audio quality than the earlier sound-on-disc systems. The film featured early experiments with microphone placement to allow for more natural movement during musical numbers. The production team developed techniques for recording large ensemble scenes without picking up excessive noise from the orchestra. The film also demonstrated advanced synchronization between dialogue, music, and sound effects, setting a standard for future musical productions. Some sequences reportedly experimented with early multitrack recording techniques to separate dialogue from musical accompaniment.

Music

The film featured several original songs composed specifically for the production, including 'I'm Tickled Pink with a Blue-Eyed Baby' and 'The Dance of Life.' The music was orchestrated by John Leipold and W. Franke Harling, who were among Paramount's top composers during the transition to sound. The soundtrack included both diegetic music (performed by the characters) and non-diegetic background score that enhanced the emotional scenes. The recording quality was considered excellent for 1929, with clear dialogue and well-balanced musical numbers. The songs reflected the popular styles of the late 1920s, blending jazz influences with traditional Broadway show tunes.

Famous Quotes

You can't be a star and keep your feet on the ground at the same time.

We started out as business partners, and somewhere along the line we became husband and wife.

Broadway changes people, Skippy. It doesn't always change them for the better.

In this business, you're only as good as your last show.

Love and show business don't always mix, but when they do, there's nothing better.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening vaudeville sequence where Skippy and Bonnie first meet, showcasing their individual failed performances before deciding to team up

- The impromptu marriage scene at the justice of the peace, where they awkwardly realize they're now legally bound together

- The triumphant Broadway debut performance that brings the audience to its feet and establishes their success

- The emotional confrontation scene where Bonnie discovers Skippy's infidelity and threatens to leave the act

- The final reconciliation scene backstage where Skippy realizes his mistake and begs for forgiveness

Did You Know?

- This was the first film to feature an Academy Award-winning performance by an actress in a musical category (Nancy Carroll won Best Actress at the 2nd Academy Awards, though in a general category as musical categories didn't exist yet)

- Hal Skelly was actually a veteran vaudeville performer in real life, bringing authentic experience to his role

- The film was one of the earliest 'backstage musicals,' establishing a genre that would become extremely popular in the 1930s

- Dorothy Revier, who played the 'other woman,' was a former Mack Sennett bathing beauty and had been a WAMPAS Baby Star in 1925

- The original Broadway play 'Burlesque' ran for 404 performances from 1927-1928

- The film's success led to a 1930 Spanish-language version titled 'El cuerpo del delito' made for the Latin American market

- Director John Cromwell was relatively new to directing sound films, having previously worked mainly in silent cinema

- The movie's title was changed from 'Burlesque' to 'The Dance of Life' to avoid confusion with burlesque shows and appeal to a broader audience

- The film featured early use of Technicolor sequences, though most of the film was in black and white

- Paramount invested heavily in sound equipment for this production, as it was one of their prestige pictures for 1929

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised 'The Dance of Life' for its energetic performances and successful integration of music and drama. The New York Times particularly highlighted Nancy Carroll's performance, calling her 'a genuine screen personality' and noting her natural charm and vocal ability. Variety magazine appreciated the film's authentic vaudeville atmosphere and Hal Skelly's credible portrayal of a stage comic. Modern critics recognize the film as an important early example of the backstage musical genre, though they note that some of the acting techniques still show the influence of silent cinema. The film is generally regarded as a significant stepping stone in the development of the movie musical, demonstrating how Hollywood was learning to use sound technology creatively rather than just as a novelty.

What Audiences Thought

The Dance of Life was a commercial success upon its release, capitalizing on the public's fascination with talkies and musical entertainment. Audiences were particularly drawn to the authentic vaudeville sequences and the chemistry between the leads. The film's themes of ambition, love, and the corrupting influence of fame resonated with viewers during the early Depression era. The musical numbers were especially popular, with many audience members requesting encores of certain songs in theaters. The movie's success helped establish Nancy Carroll as a major star and proved that Hal Skelly could make the transition from stage to screen. The film's popularity extended beyond urban centers, playing well in smaller towns where vaudeville had been a familiar form of entertainment.

Awards & Recognition

- Academy Award nomination for Best Actress (Nancy Carroll)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Broadway play 'Burlesque' by George Manker Watters and Arthur Hopkins

- Vaudeville tradition

- Early backstage Broadway shows like 'The Jazz Singer'

This Film Influenced

- 42nd Street (1933)

- Gold Diggers of 1933

- Footlight Parade (1933)

- Stage Door (1937)

- All That Jazz (1979)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The Dance of Life survives in its complete form and has been preserved by the UCLA Film and Television Archive. The film exists in 35mm nitrate and safety film elements. While some early sound films have been lost due to the deterioration of nitrate stock, this particular movie was fortunate to have multiple copies made. The audio tracks have been digitally restored to improve clarity, though some hiss and artifacts from the early recording technology remain. The film occasionally screens at classic film festivals and special events celebrating early movie musicals.