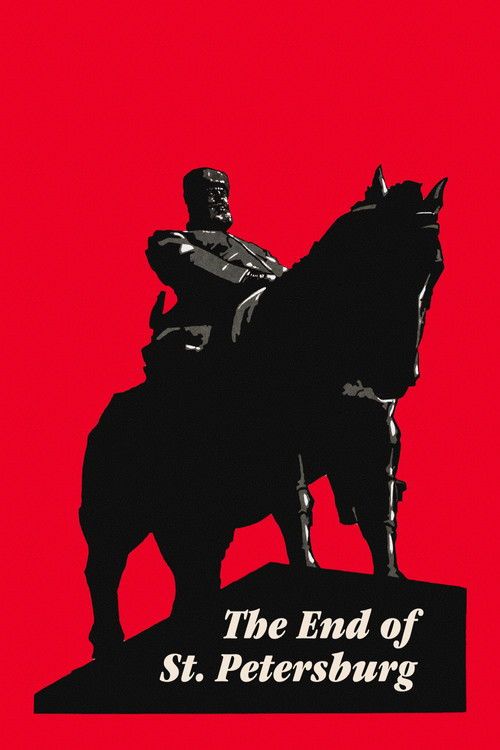

The End of St. Petersburg

"A visual poem of the Revolution."

Plot

In 1913, a naive peasant boy leaves his impoverished village for St. Petersburg, hoping to find work and support his family. Upon arrival, he stays with a Bolshevik worker but unwittingly betrays him to the factory management during a labor strike, leading to the worker's arrest. Riddled with guilt, the boy attempts to secure his friend's release but is instead beaten and imprisoned himself. When World War I breaks out, he is sent to the front lines where he witnesses three years of horrific trench warfare while capitalists at home profit from the bloodshed. Returning to a city on the brink of collapse, he reunites with the Bolshevik worker and joins the revolutionary masses in the 1917 storming of the Winter Palace, marking the symbolic 'end' of the old St. Petersburg and the birth of Leningrad.

About the Production

The film was commissioned by the October Revolution Jubilee Committee to celebrate the 10th anniversary of the 1917 Revolution. It was produced simultaneously with Sergei Eisenstein's 'October,' but Pudovkin managed to complete his film on schedule, whereas Eisenstein's production faced significant delays due to political re-editing (specifically the removal of Trotsky). Originally, Pudovkin and screenwriter Nathan Zarkhi planned an epic covering 200 years of the city's history, but they eventually narrowed the focus to the years 1913–1917 to create a more intimate, character-driven narrative.

Historical Background

The film was created during the 'Golden Age' of Soviet Montage, a period where the state heavily funded cinema as a tool for education and propaganda. It was specifically made for the 10th anniversary of the October Revolution. At this time, the Soviet government was transitioning from the New Economic Policy (NEP) toward more centralized control, and the film reflects the official 'orthodox' view of the war and the rise of the Bolsheviks. It serves as a historical document of how the Soviet state wished to be perceived: as a necessary liberation from the dual evils of Tsarism and predatory Capitalism.

Why This Film Matters

The film is a cornerstone of film theory, specifically regarding 'linkage' montage. While Eisenstein advocated for 'collision' montage (shocking the viewer), Pudovkin used montage to build emotional resonance and narrative flow. It proved that political propaganda could also be high art, influencing the 'socialist realism' that would follow, as well as Western filmmakers like Alfred Hitchcock who studied Pudovkin's techniques for building suspense and mood through editing.

Making Of

The production was a massive state-sponsored undertaking. Pudovkin and his cinematographer Anatoli Golovnya utilized authentic locations, including the actual Winter Palace, to lend the film a sense of historical weight. A major challenge was balancing the propaganda requirements of the state with Pudovkin's interest in 'lyrical' cinema and human psychology. The crew worked under intense pressure to meet the anniversary deadline, often filming in freezing conditions to capture the stark reality of the Russian winter and the muddy trenches of WWI.

Visual Style

Anatoli Golovnya used low-angle shots to give the characters a heroic, monumental quality. The film is famous for its symbolic imagery, such as the frequent use of the statue of Peter the Great to represent the weight of the old regime. The lighting is often stark and high-contrast, emphasizing the grit of the factory and the desolation of the battlefield.

Innovations

The film is a masterclass in 'associative montage.' The most famous technical achievement is the sequence where images of frantic stock brokers are intercut with soldiers dying in the mud, visually linking capitalist greed directly to the cost of human life. This rhythmic editing was revolutionary for its time.

Music

Originally a silent film accompanied by live piano or orchestra. Modern restorations often feature scores by composers like Vladimir Yurovsky or new experimental scores by groups like Harmonieband.

Famous Quotes

The end of St. Petersburg... the beginning of Leningrad. (Intertitle)

For the Tsar! For the Fatherland! (Ironical intertitle during war scenes)

While they trade in gold, we pay in blood. (Thematic sentiment conveyed through intertitles)

Memorable Scenes

- The Stock Exchange Sequence: A frantic montage intercutting the rising prices of stocks with the falling bodies of soldiers in the mud.

- The Storming of the Winter Palace: A grand, cinematic recreation of the 1917 uprising.

- The Potato Scene: A quiet, human moment at the end where a poor woman shares her last food with wounded soldiers, symbolizing communal solidarity.

Did You Know?

- The film is the middle entry in Pudovkin's 'Revolutionary Trilogy,' which also includes 'Mother' (1926) and 'Storm Over Asia' (1928).

- Director Vsevolod Pudovkin appears in a cameo role as a German officer.

- It was the first Soviet film to be screened at the Roxy Theatre in New York, then the largest cinema in the world.

- Unlike Eisenstein, who used 'masses' as his protagonist, Pudovkin focused on the psychological journey of an individual 'everyman' to explain the Revolution.

- The film's title refers to the transition of the city's name and identity from the Imperial 'St. Petersburg' to the revolutionary 'Leningrad.'

- The famous stock exchange sequence was filmed using a 'montage-board' instead of a traditional storyboard to map out the rhythmic cuts.

- The film inspired American composer Vernon Duke to write an oratorio of the same name in 1937.

What Critics Said

Upon release, it was a major critical and popular success, often preferred by contemporary audiences over Eisenstein's 'October' because of its relatable human protagonist. Modern critics praise its 'visceral intensity' and 'visual poetry.' While some find the propaganda heavy-handed, the technical execution—particularly the cross-cutting between the stock exchange and the war front—is still taught in film schools as a pinnacle of silent cinema editing.

What Audiences Thought

The film was immensely popular in the Soviet Union and had a successful international run. Audiences were particularly moved by the performance of Vera Baranovskaya and the relatable plight of the 'Village Lad' (Ivan Chuvelyov).

Awards & Recognition

- Recognized as a masterpiece of Soviet Cinema at various international retrospectives

- Honored at the 1958 Brussels World's Fair as one of the best films ever made (historical poll)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Intolerance (1916)

- The works of Lev Kuleshov

- Maxim Gorky's literature

This Film Influenced

- Reds (1981)

- The Man with a Movie Camera (1929)

- The films of Alfred Hitchcock (editing techniques)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is well-preserved and has undergone several restorations. It is widely available in high-quality editions from distributors like Kino Lorber and the British Film Institute.