The Fighting Coward

"The Man Who Wouldn't Fight - Until He Had To!"

Plot

Tom Rumford, a young Southern man sent to live with Quaker relatives in Pennsylvania during his childhood, returns to his Kentucky home as a pacifist completely out of step with the local culture of honor and violence. His peaceful demeanor and refusal to engage in duels or fights earns him the nickname 'The Fighting Coward' and makes him the subject of ridicule among the Southern gentlemen who value courage above all else. When his family's honor is challenged and his beloved Mary faces danger from the villainous Blue, Tom must find a way to reconcile his Quaker upbringing with his Southern heritage. The film follows his journey as he navigates between two conflicting value systems while trying to win respect and protect those he loves, ultimately discovering that true courage comes from conviction rather than violence. In a climactic confrontation, Tom proves that his pacifist beliefs don't make him a coward, but rather a man of principle willing to stand up for what's right.

About the Production

The film was produced during the peak of James Cruze's career at Paramount, when he was one of the studio's most prestigious directors. The production utilized elaborate sets to recreate both the Quaker community in Pennsylvania and the antebellum South. The film featured extensive location shooting for outdoor sequences, which was somewhat unusual for the period. Paramount invested significantly in period-accurate costumes and props to authenticate the Southern setting.

Historical Background

The Fighting Coward was produced in 1924, during a period of significant social and cultural transformation in America. The 1920s, known as the Roaring Twenties, saw the nation grappling with its identity after World War I, with tensions between traditional values and modern sensibilities. The film's exploration of North-South cultural differences resonated with audiences still living with the legacy of the Civil War, which had ended only 59 years earlier. This was also the height of the silent film era, with Hollywood establishing itself as the global center of cinema production. The film's themes of pacifism versus honor were particularly relevant in the post-war period, when many were questioning traditional notions of masculinity and courage. The year 1924 also saw the rise of the second Ku Klux Klan, making the film's nuanced portrayal of Southern culture particularly significant.

Why This Film Matters

The Fighting Coward represents an early example of Hollywood's exploration of regional American identities and cultural conflicts. The film contributed to the popular genre of 'fish out of water' stories that would become a staple of American cinema. Its treatment of pacifism as a form of courage rather than weakness was relatively progressive for its time, offering an alternative to the typical macho hero archetype prevalent in 1920s films. The movie also reflects the era's fascination with the 'Lost Cause' mythology of the Old South while simultaneously questioning its values. As a silent film, it demonstrates how complex themes could be conveyed through visual storytelling and pantomime, showcasing the sophistication of late silent-era cinema. The film's exploration of cultural identity and personal conviction continues to resonate in contemporary discussions about regional differences and moral courage.

Making Of

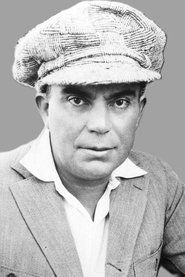

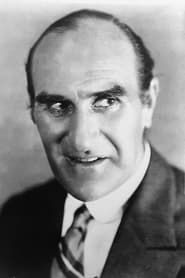

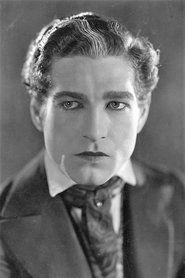

Director James Cruze was known for his meticulous attention to detail and his ability to extract nuanced performances from his actors. For 'The Fighting Coward,' he worked closely with the cast to develop the cultural contrasts between the Quaker and Southern lifestyles. Ernest Torrence, who stood at 6'4" and had an imposing presence, was cast against type as a character who initially appears threatening but ultimately reveals depth. The production faced challenges in creating authentic period settings, with the art department working extensively to ensure both the Pennsylvania Quaker community and Kentucky plantation settings were historically accurate. Mary Astor, still early in her career, received guidance from Cruze on how to portray a Southern belle with both charm and strength. The film's action sequences were carefully choreographed to highlight the contrast between violence and non-violence, a theme that Cruze emphasized throughout the production.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Karl Brown utilized the visual language of silent cinema to emphasize the cultural contrasts at the heart of the story. The Quaker scenes were shot with softer lighting and more static compositions to convey the peaceful, orderly nature of that community, while the Southern sequences featured more dynamic camera movement and dramatic lighting to reflect the passionate, volatile atmosphere. Brown employed careful framing to highlight the physical presence of Ernest Torrence and the delicate features of Mary Astor, creating visual contrasts that reinforced their character dynamics. The film made effective use of location shooting for outdoor scenes, particularly in sequences depicting the Kentucky landscape, which added authenticity to the production. Interior scenes were carefully lit to create the appropriate mood for each setting, with the Quaker meeting house scenes featuring natural light effects while the plantation interiors used more dramatic chiaroscuro.

Innovations

The Fighting Coward utilized several technical innovations common to mid-1920s Paramount productions. The film employed the latest in lighting technology, including the use of artificial sunlight effects for outdoor scenes shot on studio sets. The production made extensive use of multiple camera setups, allowing for more dynamic editing and visual variety than earlier silent films. The costume department created historically accurate period clothing using advanced dyeing and fabric treatment techniques available in the 1920s. The film's special effects, while minimal, included carefully orchestrated stunt sequences that required precise timing and coordination between performers and camera operators. The movie was shot on standard 35mm film with an aspect ratio of 1.33:1, which was typical for the era, but the cinematography made creative use of this format through careful composition and movement.

Music

As a silent film, The Fighting Coward would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The score would have been compiled from various classical pieces and popular songs of the era, selected to match the mood of each scene. The Quaker sequences would likely have featured more subdued, religious-themed music, while the Southern scenes would have incorporated more lively, romantic compositions. Theaters often employed full orchestras for major productions like this Paramount release, with the music carefully synchronized to the on-screen action. The film's climactic scenes would have been accompanied by increasingly dramatic musical selections to heighten the emotional impact. Unfortunately, no original cue sheets or specific musical selections for this film have survived, which was common for many silent productions.

Famous Quotes

A man's courage is measured not by his willingness to fight, but by his readiness to stand for his convictions.

Honor is not found in the drawing of a gun, but in the strength of one's principles.

They call me coward because I will not kill, but I ask you, who is the braver man - he who follows the crowd, or he who follows his conscience?

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence showing young Tom Rumford being sent away from his Southern home to live with Quaker relatives, establishing the cultural divide that drives the narrative.

- The scene where Tom first returns to his Southern home and is mocked for his pacifist beliefs, highlighting the cultural clash.

- The climactic confrontation where Tom must choose between his Quaker principles and protecting his family's honor, demonstrating his growth as a character.

Did You Know?

- This was one of several collaborations between director James Cruze and star Ernest Torrence, who frequently played imposing character roles in Cruze's films.

- Mary Astor was only 18 years old when she appeared in this film, early in her long and distinguished career that would span over four decades.

- The film's theme of cultural clash between North and South reflected ongoing tensions in American society nearly 60 years after the Civil War.

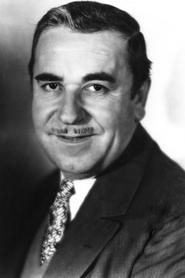

- Noah Beery, who plays the villain, was the father of actor Noah Beery Jr. and the older brother of Wallace Beery, creating a notable acting dynasty.

- The film was based on a story by playwright and screenwriter Waldemar Young, who frequently collaborated with legendary director Cecil B. DeMille.

- James Cruze was known for his ability to handle both epic spectacles and intimate character dramas, and this film showcased his versatility.

- The film's title was somewhat ironic, as the protagonist's journey involves discovering that true courage has nothing to do with violence.

- Paramount marketed the film as both a comedy and a drama, reflecting the complex tone of the story.

- The film was released during the height of the silent era, just a few years before sound would revolutionize Hollywood.

- Ernest Torrence, despite his intimidating presence, was actually classically trained and had a background in opera before turning to acting.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised James Cruze's direction and the performances of the lead cast, particularly Ernest Torrence's nuanced portrayal of a character struggling between two value systems. The film was noted for its effective blend of comedy and drama, with reviewers highlighting how it managed to address serious themes while maintaining entertainment value. The New York Times praised the film's 'sincere treatment of a difficult subject' and commended Torrence's performance as 'both powerful and restrained.' Variety noted the film's 'unusual depth for a comedy' and predicted it would find favor with audiences seeking more than simple entertainment. Modern film historians have recognized The Fighting Coward as an example of Cruze's sophisticated approach to genre filmmaking, with some scholars pointing to its subtle critique of Southern honor culture as ahead of its time.

What Audiences Thought

The Fighting Coward performed moderately well at the box office upon its release, appealing to audiences who appreciated James Cruze's reputation for quality filmmaking. Viewers responded positively to the film's humor while also engaging with its more serious themes about courage and conviction. The contrast between Northern and Southern cultures resonated with audiences in both regions, though some Southern viewers found the critique of honor culture somewhat pointed. The film's blend of comedy with thoughtful drama was seen as a refreshing change from more straightforward genre pictures of the era. Mary Astor's performance was particularly popular with male audiences, while Ernest Torrence's character arc was praised by viewers who appreciated stories of personal growth and moral courage.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The Birth of a Nation (1915) - for its portrayal of Southern culture

- Way Down East (1920) - for its moral themes and dramatic structure

- The Covered Wagon (1923) - James Cruze's previous success with American themes

This Film Influenced

- The Virginian (1929) - similar themes of Western honor codes

- The Plainsman (1936) - cultural conflict themes

- Gone with the Wind (1939) - Southern cultural depiction

You Might Also Like

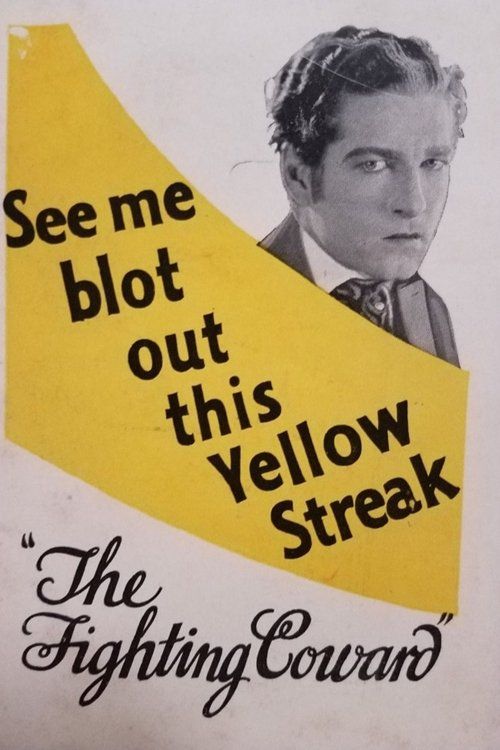

Film Restoration

The Fighting Coward is considered a lost film. No complete copies are known to exist in any film archives or private collections. This status is unfortunately common for silent films, as an estimated 75% of American silent films have been lost due to deterioration, neglect, or the destruction of nitrate film stock. Some production stills and promotional materials survive, which provide some visual documentation of the film, but the actual moving images have not been preserved. The loss of this James Cruze film represents a significant gap in the director's available filmography and in the documentation of 1920s cinema.