The Girl from the Marsh Croft

Plot

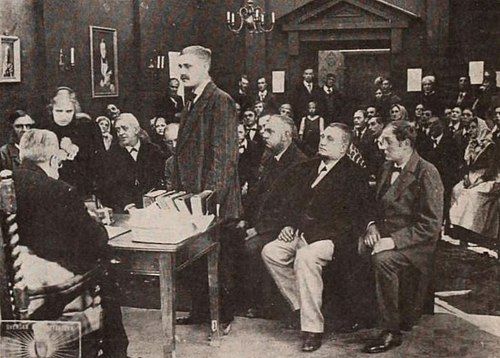

Helga, a young woman from a humble marsh croft, has given birth to a child out of wedlock to a much older married man, Gudmund Erlandsson. When Erlandsson refuses to pay child support and publicly denies being the father, Helga's honorable father insists they take legal action. The case proceeds to court, where Erlandsson prepares to swear on the Bible that he is not the child's father. In a dramatic moment of moral clarity, Helga suddenly withdraws the case, explaining that while Erlandsson is indeed the father, she cannot allow him to commit perjury—a crime and mortal sin—despite his betrayal of her. The film concludes with Helga finding redemption through her moral courage, eventually marrying a kind man who accepts her and her child.

About the Production

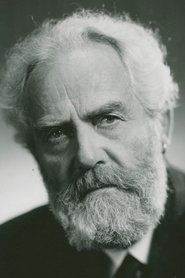

This was the first film in Victor Sjöström's celebrated series of Selma Lagerlöf adaptations, made possible by a groundbreaking deal between the Nobel Prize-winning author and Svenska Biografteatern. Lagerlöf had previously refused all film adaptation requests for years, but was so impressed by Sjöström's 1917 film 'Terje Vigen' that she agreed to allow adaptations of her works. The film was shot during the golden age of Swedish cinema, when the country was producing some of the most artistically sophisticated films in the world. The marsh croft setting was carefully recreated to authentically represent rural Swedish life of the period.

Historical Background

The film was produced during World War I, a period when Sweden remained neutral and its film industry flourished while European film production was disrupted elsewhere. This neutrality allowed Swedish cinema to develop independently and gain international prominence. The year 1917 was particularly significant for Swedish film, marking what historians consider the beginning of the country's golden age of cinema. The film's themes of morality, social justice, and personal responsibility resonated strongly with audiences dealing with the moral uncertainties of wartime. The adaptation of Nobel Prize winner Selma Lagerlöf's work also represented a growing cultural acceptance of cinema as a legitimate art form capable of handling serious literary material.

Why This Film Matters

'The Girl from the Marsh Croft' holds immense cultural significance as a landmark in Swedish cinema history and as an early example of literary adaptation done with artistic integrity. The film helped establish the template for adapting serious literature to the screen, proving that cinema could handle complex moral themes with the same depth as literature. It also contributed to the international reputation of Swedish cinema as artistically sophisticated and psychologically nuanced. The film's success paved the way for more literary adaptations and helped elevate cinema's cultural status in Sweden. Additionally, it represented an early feminist narrative, centering on a woman's moral agency and strength in the face of social condemnation, themes that were quite progressive for 1917.

Making Of

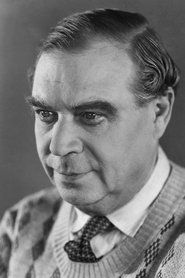

The making of 'The Girl from the Marsh Croft' marked a turning point in the relationship between literature and cinema in Sweden. Victor Sjöström had to convince the notoriously protective Selma Lagerlöf that her literary work could be faithfully adapted to the screen. After she watched his film 'Terje Vigen,' Lagerlöf was moved to tears and agreed to the collaboration. The production team worked closely with Lagerlöf to ensure the adaptation remained true to the novel's themes of morality, redemption, and social justice. The casting of Greta Almroth as Helga was particularly significant, as her naturalistic acting style perfectly embodied the character's quiet strength and moral courage. The film was shot on location in rural Sweden to capture the authentic atmosphere of the marsh croft setting, with cinematographer Julius Jaenzon employing innovative lighting techniques to create the moody, atmospheric quality that became characteristic of Swedish cinema of this period.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Julius Jaenzon was groundbreaking for its time, employing natural lighting and location shooting to create an authentic Swedish atmosphere. Jaenzon used innovative techniques such as soft focus lighting for emotional scenes and careful composition to emphasize the psychological states of the characters. The marsh croft setting was captured with a poetic realism that balanced the harshness of rural life with moments of visual beauty. The courtroom scenes featured dramatic lighting contrasts to emphasize the moral tension, while close-ups were used judiciously to highlight emotional moments. The cinematography helped establish the visual style that would become characteristic of the Swedish Golden Age of cinema.

Innovations

The film showcased several technical innovations for its time, particularly in its use of location shooting rather than relying entirely on studio sets. The production employed natural lighting techniques that were advanced for 1917, creating more realistic and atmospheric images. The film's editing, particularly in the courtroom sequence, demonstrated sophisticated understanding of pacing and dramatic tension building. The use of close-ups for emotional emphasis was more restrained and purposeful than in many contemporary films, showing Sjöström's understanding of their psychological impact. The film's preservation of visual quality in exterior scenes was notable for the period, demonstrating the technical expertise of the Swedish film industry.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Girl from the Marsh Croft' would have been accompanied by live musical performance in theaters. Original scores were typically not standardized, with each theater providing their own musical accompaniment based on cue sheets provided by the studio. The music would have ranged from classical pieces to original compositions designed to enhance the emotional impact of key scenes. For modern restorations, new scores have been composed by contemporary musicians specializing in silent film accompaniment, often using a combination of period-appropriate instruments and modern sensibilities to create an appropriate emotional atmosphere.

Famous Quotes

While the film is silent and contains no spoken dialogue, the intertitles convey key moral messages including Helga's statement: 'I cannot let him swear a false oath on God's holy book, even though he has wronged me.'

Memorable Scenes

- The climactic courtroom scene where Helga dramatically withdraws her case to prevent the father of her child from committing perjury, demonstrating her moral superiority despite his betrayal. The scene is built with careful pacing, using close-ups to capture the emotional intensity and moral weight of Helga's decision.

Did You Know?

- This was the first of seven Selma Lagerlöf adaptations that Victor Sjöström would direct, establishing a legendary collaboration between director and author.

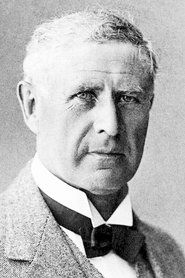

- Selma Lagerlöf, who won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1909, had previously refused all film adaptation requests for years before seeing Sjöström's work.

- The film's success helped establish Swedish cinema's international reputation for artistic quality and psychological depth.

- Greta Almroth, who played Helga, became one of Sweden's most prominent silent film actresses of the 1910s.

- The courtroom scene was considered particularly innovative for its time, using close-ups and dramatic pacing to build tension.

- The film was part of what film historians now call the 'Golden Age of Swedish Cinema' (1917-1924).

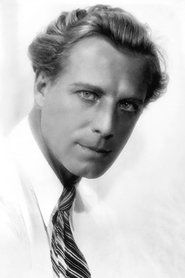

- Lars Hanson, who played the male lead, would later have a successful career in Hollywood during the late silent era.

- The original novel 'Tösen från Stormyrtorpet' was one of Lagerlöf's more socially conscious works, addressing themes of morality and class.

- The film was distributed internationally, helping introduce Swedish cinema to audiences beyond Scandinavia.

- Sjöström's naturalistic directing style in this film influenced many contemporary filmmakers across Europe.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film for its artistic merit and faithful adaptation of Lagerlöf's novel. Swedish critics particularly noted the film's psychological depth and naturalistic performances, with special acclaim for Greta Almroth's portrayal of Helga. International critics, when the film was exported, marveled at the sophistication of Swedish cinema, with many reviews highlighting the film's moral seriousness and technical excellence. Modern film historians consider the work a masterpiece of early Swedish cinema, often citing it as an example of how silent film could achieve profound emotional and psychological effects without dialogue. The film is frequently studied in film history courses as an exemplary work of the Swedish Golden Age.

What Audiences Thought

The film was enormously popular with Swedish audiences upon its release, drawing large crowds and generating significant discussion about its moral themes. Audiences were particularly moved by Helga's moral courage in the courtroom scene, which became one of the most talked-about moments in Swedish cinema of 1917. The film's success at the box office helped establish Svenska Biografteatern as a major force in European cinema. International audiences also responded positively when the film was exported, with many viewers noting the distinctive Scandinavian atmosphere and emotional authenticity. The film's themes of redemption and moral strength resonated strongly with audiences dealing with the uncertainties of the wartime period.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Selma Lagerlöf's novel 'Tösen från Stormyrtorpet' (1913)

- Swedish literary tradition of social realism

- Contemporary Scandinavian cinema movement

- Victor Sjöström's earlier work 'Terje Vigen'

This Film Influenced

- Subsequent Selma Lagerlöf adaptations by Sjöström

- Swedish films of the Golden Age

- International art cinema of the 1920s

- Later courtroom drama films

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved and restored by the Swedish Film Institute. While some deterioration occurred over the decades, a complete version exists and has been made available for modern viewing. The restoration work has helped maintain the visual quality of this important early Swedish film, ensuring its place in cinema history remains accessible to scholars and enthusiasts.